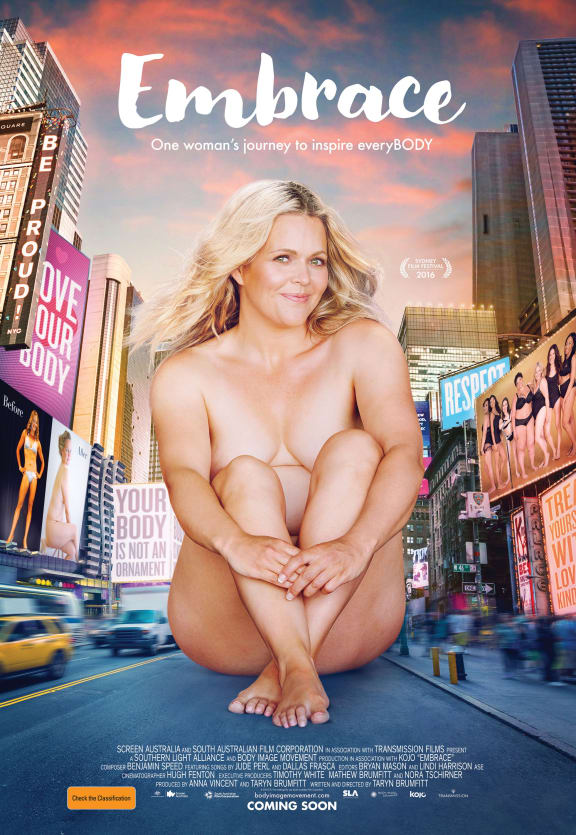

An Australian documentary that discusses body image and shows female genitalia was one of the biggest talking points of this years’ New Zealand International Film Festival.

Deputy chief censor Jared Mullen Photo: Supplied

The film Embrace was given an MA15+ rating [Legally restricted to persons 15 years and over] in Australia, while our censors saw it as educational and rated it 'M' [Unrestricted, but more suitable for mature audiences] with notes for offensive language and nudity.

Jarrod Mullen is the Deputy Chief Censor of Film and Literature, who has been in the role just over a year.

Eva Radich talks to him about Embrace, the desire of Kiwis to know "what's in the tin" and why our censorship legislation needs to change.

Edited highlights

On rating the documentary Embrace:

Jarrod Mullen: Anything that arrives with a prior unrestricted rating from Australia or the UK can carry the equivalent rating here. But if something hasn’t been rated in those countries or it has been restricted in one of them then New Zealand censors have to examine it.

The poster for Australian documentary Embrace. Photo: Twitter

We examined Embrace because the Australian censors had applied a restriction to it [MA15+]. It did, I think, highlight the differences in Australian and New Zealand law in this regard, but also I think in terms of societal values. The film was restricted in Australia primarily due to nudity. In New Zealand, nudity isn’t necessarily something we would restrict for.

The Australians are bound by their legislation in this regard. One of their guiding principles is ‘Look at the standards of morality and decency generally accepted by reasonable adults’. Whereas New Zealand censors can only restrict something if it contains sex, horror, crime, cruelty or violence.

Because of the subject matter, ‘Embrace’ deals with [female body image] it does deal very lightly with some of the sexualised portrayals of women in the media, but those weren’t of significance to trigger a threshold.

We’re talking about a long documentary – 80, 90 minutes – but there are only a few brief seconds in the film where female genitalia are displayed. In one particular segment a range of healthy female genitalia are displayed – but only to show the range of female body types. And there’s nothing sexual about that.

On his role as Deputy Chief Censor:

I told an audience the other day this is the only job I’ve ever applied for that the only reason I applied for it was because I wanted to do it.

I think it’s such a core public service. It acts to provide New Zealanders with vital information that they want and need, particularly New Zealand parents, and it has a protective element, too, for New Zealand society based on our unique New Zealand values.

We do look at material referred to us from Internal Affairs – it can be from police, it can be intercepted by customs. And most of what they refer to us is potential images of child sexual abuse, and we have to exercise judgment according to the legislative criteria to classify those. But not always - there can be strong images of violence.

On censorship legislation in New Zealand today:

We [the Office of Film and Literature] have got our act – the Films, Videos and Publications Act – and that has traditionally dealt with anything that you see onscreen, magazines, books, video store… Anything that you might pick up by way of consumer video.

The Broadcasting Act (1989) was designed to regulate radio and free-to-air TV, basically.

[Internet streaming services] don’t fit into either neatly. In one sense you could look at them as a form of broadcast, in another sense they’ve simply replaced the DVDs and videos people used to get.

The public have told us they want consistent classifications, no matter what they’re looking at or how they choose to watch or play. 92% of people said labels were extremely important when choosing entertainment for children and young people. It indicates an extremely protective role New Zealand parents want to be supported in. So I think regardless of what happens, the content regulation regime has to be consistent across [all forms of content].

The Chief Censor and I are particularly pleased that there are a large number of providers (particularly the multinational ones) who regard compliance as just part of the way they do business. Netflix, Google Play, iTunes – all of those big providers pick up New Zealand classifications and ratings consistently.

The Chief Censor and I have been quite concerned with some of the things that Lightbox has rated itself. There’s a ballet drama series called Flesh and Bone. It's set in the gritty world of New York ballet and deals with a young dancer who comes into that world. It portrays quite graphic violence, it portrays sexual violence, sexual assault. It has nudity and frequent use of offensive language, there’s drug use.

The nature and extent of all of those things led to an official rating (when we rated the DVD set) of R18, with notes for sex and violence and drug use. Lightbox originally screened Flesh and Bone with an R16 rating and no notes. If you’ve got a teenage daughter who’s interested in ballet and they click on this series, they’re going to see all of that.

New Zealand parents tell us they want to know what’s in the tin. I think Kiwis are like that. Whether it’s a tin of baked beans or the entertainment they watch, they want to know. They want a reliable label.

If you’ve got a consistent commercial consumer information regime you’re still going to catch most of what Kiwi parents are concerned about. What the office can’t do, though, is be in every teenager’s bedroom… and nor can parents.

Form has to follow function, but the function is clear. New Zealanders have told us that they want one labelling regime to cover all content – regardless of how they watch.