Iconic British music publication NME recently announced it would no longer publish a print edition of the music weekly which has been running for 66 years. We take a look back at the magazine’s history with Pat Lon – author of The History of the NME - High Times and Low Lives at the World's Most Famous Music Paper.

Photo: Supplied

This interview was first broadcast on November 17, 2012.

UK music newspaper the New Musical Express, or NME was first published in 1952 and went on to shape global music taste, including New Zealand’s.

Pat Long is the author of The History of the NME - High Times and Low Lives at the World's Most Famous Music Paper. Trevor Reekie talks to the ex NME writer about deadlines, drugs and rock 'n' roll.

One thing I never knew about NME was its humble beginning back in 1952 when it morphed from the Accordion Weekly into New Musical Express.

Well, it's a really strange story, but in the late 1940s there was a huge fad in Britain for accordion music, and it was so big that the accordion bands had their own newspaper, the Accordion Weekly. [Eventually] Accordion Weekly was bought by The Musical Express.

That was Maurice Kinn, was it?

That was a little bit before that. The Musical Express was floundering slightly, and it wasn't selling very much. The guys that owned it phoned up Maurice Kinn who was a promoter. He promoted and managed bands.

The owners of The Musical Express phoned him up and said, "Look, we're really struggling here, we're ready to offload this paper to you." For not very much money, it was about 1,000 pounds.

Maurice Kinn, his wife Berenice and Billy Daniels in 1957 Photo: Harry Hammond / V&A

He'd had no experience in journalism at all. Never run a newspaper before. And he bought this paper on a whim, you know. It was this failing paper and he reinvented it and relaunched it as The New Musical Express in February 1952, and that was how it started.

He was quite a canny guy because he realized that this was at a time, in the early 1950s, when people were beginning to stop buying sheet music, and [starting to buy] recorded music – buying records, 78s and the first 45s, so it was this sort of cultural shift.

People were starting to buy more records, people were buying more record players obviously, so NME really coincided with the birth of that whole culture. And then a few years after that, you get the first rock and roll records, in 1955. And no one else, certainly not in Britain, covered that music in the way that NME did. Everyone else was really dismissive about it, particularly the Fleet Street newspapers at the time.

You mentioned that Maurice Kinn was quite a savvy sort of guy, and I think one of the things that demonstrated that savvy-ness was the publishing of a record sales chart, which gave it a bit of an edge over Melody Maker. NME was the first to do that, wasn't it?

Yeah, NME invented the charts really, in Britain. And that was a hugely influential idea really. No one had compiled that before. So what they did was they had the guy who was the paper's accountant, and did all the payroll and stuff, he just had a team of about four or five people who just phoned up record shops and said, "What's been selling this week?" And they totted it all up at the end of the week and created the first chart, in Britain at least. I mean, it was an idea that they'd pinched from an American newspaper called Billboard.

It seemed that Maurice Kinn’s other really big marketing coup was setting up and marketing his innovation – the annual NME Poll-winners concert, which I guess was the '60s equivalent of the Brit Awards because he sold it to TV as well. Do you think that was the beginning of NME as a brand?

Yeah. Those poll-winners concerts were amazing really, I mean, if you look at the film, particularly in the '60s, you'd have The Beatles, The Stones, The Kinks, The Walker Brothers – all these huge, legendary acts on the same bill.

They were these afternoon concerts and every band would have exactly 15 minutes, even the headliners – It's an incredible thing really. So I suppose you're right, that that was a really important branding thing.

Dusty Springfield and The Echoes at an NME concert in 1965 Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By the time the album era came around, that was a time when Vietnam was happening, it was '68, riots happened, fashion and politics were definitely part of a pop counter-culture zeitgeist moment really. Was it the musicians who led that charge, or was it the alternative press, NME and the likes, that were creating a lot of that as well?

I don't know what the answer is really, but it certainly wasn't the NME. By that stage, you've got the underground press, the alternative press, and the birth of album culture. And the NME in the late '60s is really out of touch with all of that because it was run by a guy – Maurice Kinn, who belonged to the big band era. He was a dinosaur really, and he didn't know anything. He didn't even like Elvis, let alone Jefferson Airplane or whatever.

That was important in terms of the culture around him. Even throughout the '60s, the journalists who worked at I were expected to wear suits and ties, and have short hair, and clean fingernails and stuff.

NME really, hit its sales peak around The Beatles, in the early '60s, but within five or six years it had almost vanished, it sold so few copies.

So in the early 1970s, Maurice Kinn sold the paper and the new owners were about to shut it down, but they called the editor into their head office and said, "Listen, you've got two months to turn this around."

So what he did, the editor, this guy called Alan Smith, he just went through all the underground press and poached all their star writers basically, because he was able to offer them better money, and a regular pay packet, and a bigger audience.

Photo: RNZ

So then you've got people like Nick Kent, Charles Shaar Murray, and later on Mick Farren, and that saved the paper really, and it became the NME that I guess most people know today.

It became a kind of counter-cultural voice, even though it was published by a huge multi-national publishing corporation. It became a kind of voice of the underground, or a voice of the alternative.

The editor obviously has a crucial job. Tell us, based on your research, what makes for a great editor, besides selling papers?

Okay. I don't know. You've got to be pretty tolerant, I think, and patient, because a lot of these people who are the star writers were absolute liabilities.

You can only laugh at some of the Nick Kent stories.

Yeah, that's right. I interviewed a woman who still works there, who's the editor's PA and has been the editor's secretary since the early 1980s, and she said on the first day she was at work she was taken round the office and shown where everything was.

They took her to the kitchen and said, "You'd better bring your own teaspoon if you want tea." Because all the teaspoons in the kitchen were black from some of the journalists cooking up heroin. That kind of behaviour, from an editor's point of view, I don't know how you deal with that other than just be patient.

And make sure that the copy comes in on time.

That's right, yeah. Famously Nick Kent would deliver his copy in longhand on scraps of whatever paper was to hand, so the back of cigarette packets, and on bus tickets and all this kind of stuff, and deliver this big pile like a collage of paper with all his reviews written on them, and give it to someone and say, “Type this up!” Five minutes before the deadline.

So it was a pretty chaotic place, really. And sometimes you wonder how they managed to get the newspaper out at all.

NME has always been blessed with star writers, and some of them were real risks, for example, Nick Kent, Tony Parsons, and Julie Burchill later on. And later in the '90s, the likes of Johnny Cigarettes. What did these people have that really defined new talent?

Good question really. I don't know. They were all just extremely talented writers, I guess. But more than that I think, actually, they were really vested in what they were writing about. They had a real passion for the subject matter. They really cared, and were really informed about the culture they were writing about.

This was a time, 30, almost 40 years ago, when rock and roll had its own kind of distinct underground culture that surrounded it, that was in total opposition to the mainstream in a way that doesn't really exist anymore, I don't think.

So there was a whole culture that grew up around music, and all the stuff that went with music, the lifestyle around music. NME didn't just write about music, but it wrote about cult books, and drugs, and radical politics, and green politics. It had a really good film section.

Photo: Midnight Raver

There was a whole culture that these people were describing and they were really at the centre of it, they were big stars, these people. At its peak, the NME was selling about a quarter of million copies a week in Britain. But the publishers reckon that four people read every issue, so essentially the audience was like a million people a week. And they were big stars, these guys. They were a big deal.

Do you think in some respects that the NME, because it was so focused on guitar, especially alternative bands, that it backed itself into a wall in some respects? Because I read for example, when punk exploded it was quite divisive, even within NME wasn't it?

That's right, yeah. Well, not just the NME, I think, but a lot of people struggled with the idea of punk really. Not everyone wanted to throw away their Led Zeppelin records and get some skinny jeans and cut their hair. So within NME specifically, punk was very divisive because you had people who were in very tight with all the stuff that punk was supposed to be clearing away.

But in the end, obviously punk was a huge boon for NME, in terms of its sales and its influence.

And I guess NME hiring the likes of Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, that makes it quite an inspired move.

That's right, yeah. And it was a small world that they inhabited and they reported on really. It led to real tensions in the office between the punk writers and the old guard as it were. And some days it led to fist fights. Tony Parsons punching Mick Farren in the face in the NME office. So that kind of gives you a flavour of the atmosphere of this magazine office.

Would it have been punk and Britpop perhaps that would've been the highest times for NME?

I guess so, yeah, certainly in terms of sales, but also in terms of influence I suppose as well, because the NME was kind of synonymous with both of those things, if you like. And during Britpop you've got kind of the widespread popular acceptance of the internet, and the growth of online publishing, which in a lot of ways, has kind of signalled the death knell for print journalism in all forms.

But before that I think they kind of missed the acid house and the DJ rise as well, didn't they? To a certain extent, even hip hop. Do you think that's right?

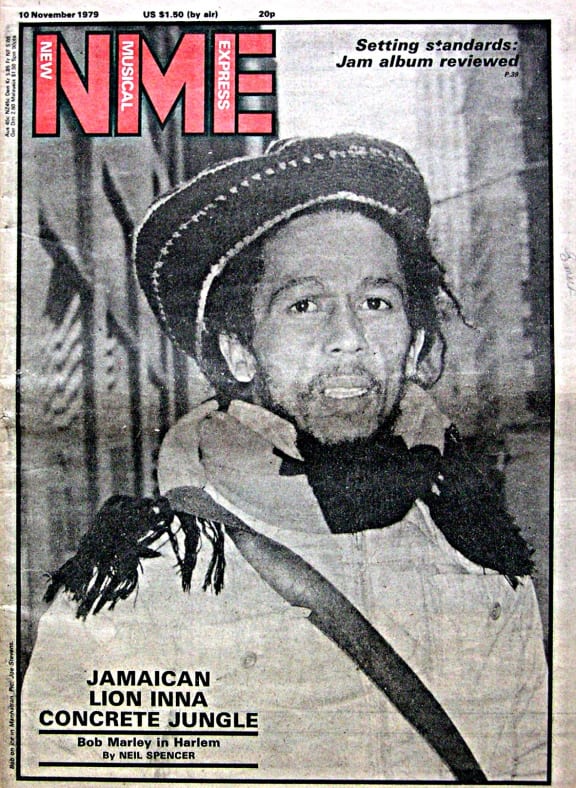

Yeah, that's right. I mean they did cover that stuff, but as I say, the NME's bread and butter is kind of white rock music, although actually, throughout its history, they've always covered things like reggae very well. Bob Marley was on the cover of the NME loads in the '70s.

But, you're right, when it got to the 1980s and you've got the acid house boom, and the early hip hop and techno and the rise of DJ culture, NME couldn't really get to grips with that at all, they were quite dismissive of it, I think.

But also because there weren't any stars from that scene. All the big records of the early acid house scene were made by just these faceless producers, so there wasn't anyone really to put on the cover of the paper, if you were gonna cover that kind of stuff.

And then the other extreme, the other thing that's happening at that time was the lo-fi, kind of indie rock revival, I mean, obviously The Smiths were a key band for NME, but you've got all this kind of jingly jangly indie stuff, and again, they didn't really have any stars either.

It was really difficult for the NME to know what to do with itself, because on the one hand there wasn't anything that said, well we're The New Musical Express so we should be writing about new music, so that means hip hop, but we don't really know how to deal with it, and don't really understand it.

And on the other hand, what they really are interested in is guitar music, but there are not really any stars in terms of guitar bands to put on the cover, so yeah, it was a difficult thing.

And it was only really resolved, I think, with the rise of bands like The Happy Mondays, and The Stone Roses, who, in Britain at least, were huge, huge acts, and big sellers for the NME as well. And interesting characters, I mean, that's everything, it is a newspaper, you need to have these kind of maverick, interesting, strange looking people to put on your cover every week.

So the biggest stars really, for NME are people like Ian Dury, or Jarvis Cocker, or people who've got something to say, that look good, and are interesting and erudite. These are kind of the heroes of the NME, I think.

Even Oasis?

And even Oasis, who probably don't look very good, and they're certainly not very erudite, but they've been on the cover of the NME more than any other act.

The NME was always a great sort of detector for talent, wasn't it? But at the same time, it wasn't beyond sort of building them up and cutting them down either.

Of course, yeah. And one of the interesting things, or funny things for me, going back; I spent a lot of time in the British Library in London, going back and reading all these old issues of the NME, and one of the interesting things is looking at the names of the bands that they really hyped up as the next big thing, and never did anything.

Forgotten names of groups that the NME lauded to high heaven, who just flopped. So they weren't always right, but when they were right it was great.

They were fiercely independent and they certainly didn't pander to the rock stars' over-inflated egos. They weren't beyond calling people like Freddie Mercury, or Brian Ferry, calling them out on their pomposity if they thought it was important.

So, yeah, they really were a force of their own. They constantly were getting in trouble with the publishers for being rude about people, and having record company advertising being pulled. So they answered to no one really, I think, apart from themselves.