The costs of installing an effective water treatment system is prohibitive for many small towns and communities, Water New Zealand says.

Photo: 123RF

The Havelock North Drinking Water inquiry, which was published yesterday, found that one in five New Zealanders are at risk of getting sick and universal treatment of drinking water is needed.

The report warned nearly 800,000 New Zealanders - or 20 percent of people on town supply - are drinking water that is "not demonstrably safe".

John Pfahlert, chief executive of Water New Zealand, says “demonstrably safe” means the water being supplied does not meet the requirements of the country’s drinking water standards, which were put in place 10 years ago.

“They set limits on the number of bacteria and chemical contaminants water can have and effectively when councils monitor their water supplies, they are supposed to be able to demonstrate that their water supply meets those standards.”

He says small towns with a population of less than 10,000 are most at risk. There are hundreds of these ‘towns’ - which include marae, rural schools and small communities with less than 500 people - throughout the country that don’t have a proper treatment system set up.

“The cost of introducing or installing effective water treatment systems is expensive when you start getting down to really small communities, because if the district or city councils want to rate those communities for the actual cost of installing or running them, the costs are almost prohibitive,” Pfahlert says.

This has resulted in a situation where many small communities are provided drinking water without effective treatment systems, or with systems that are being operated by people who don’t have the necessary skills to run them properly.

John Pfahlert CEO Water NZ Photo: Supplied

He says the only effective solution the inquiry suggested was to make the treatment of all drinking water supplies mandatory. At the moment all the drinking water standards say is a council has to take all practicable steps to meet a set of regulations they are required by law to adhere to.

“Frequently what [councils] do is hide behind arguments of technical complications or economic affordability or the community doesn’t like the taste of chlorine in their water or whatever and say that it is not practical to do anything.”

Water New Zealand and Local Government NZ have previously argued that if the government is going to impose greater requirements on small communities they should reintroduce a subsidy scheme that will allow the treatment facilities to be purchased and built for the communities by the Crown.

He says chlorination is relatively cheap for a small community, and estimates installation of a chlorination plant for a community of about 100 would cost about $10,000.

“It is possible to do this and there is no denying the fact that one of the elements that the inquiry hasn’t really turned its mind to is the affordability of this.”

Sometimes the source water being drawn from is of a lower quality to start with, such as from surface water like a river or lake, which means that the treatment facility will be more technically complicated, and therefore more expensive, to build and run.

Pfahlert says it is more cost effective to have proper water treatment systems in place, than have a health crisis like what happened in Havelock North.

The Havelock North inquiry also recommends greater protection of drinking water sources, which is a broader issue related to environmental controls, Pfahlert says.

“We absolutely need to make sure that the rivers are swimmable in New Zealand and [ensure] the water is of the best quality possible… those types of controls are dealt with through the Resource Management Act.”

There has been a push back from some communities about water chlorination, but based on the evidence, Water New Zealand says introducing compulsory treatment is in the best public interest.

To avoid the risk of contamination to communities, there needs to be changes to the way water is supplied, Pfhalert says.

“If you take deep, pure water… as soon as you put it into the reticulation network, you are running your water in the same trenches or right beside the sewerage treatment pipes that are coming out of everybody’s house and through the streets… so you have the risk of contamination.

“No it doesn’t happen very often, but there is always that potential.”

The function of regulation needs to be taken away from the Ministry of Health, Pfhalert says.

“There needs to be an independent regulator established to oversee the regulation of drinking water quality in this country. A dedicated organisation with its own legislation reporting separately to the Ministry of Health with dedicated people employed to do the job.”

With an unseasonably hot start to summer, there are concerns about drought in many parts of the country. Drought does increase the risk of water contamination, Pfhalert says, but it is ‘storm events’ that often cause animal faeces to be washed into drinking water catchments.

“Certainly there are climate change issues, which are another factor associated with both the drinking water supply and effects on aquifers and so on that are a concern, but they are medium- to long-term issues and the current issues that we’ve got in front of us are ones that can actually be dealt with immediately if the government has a will to.”

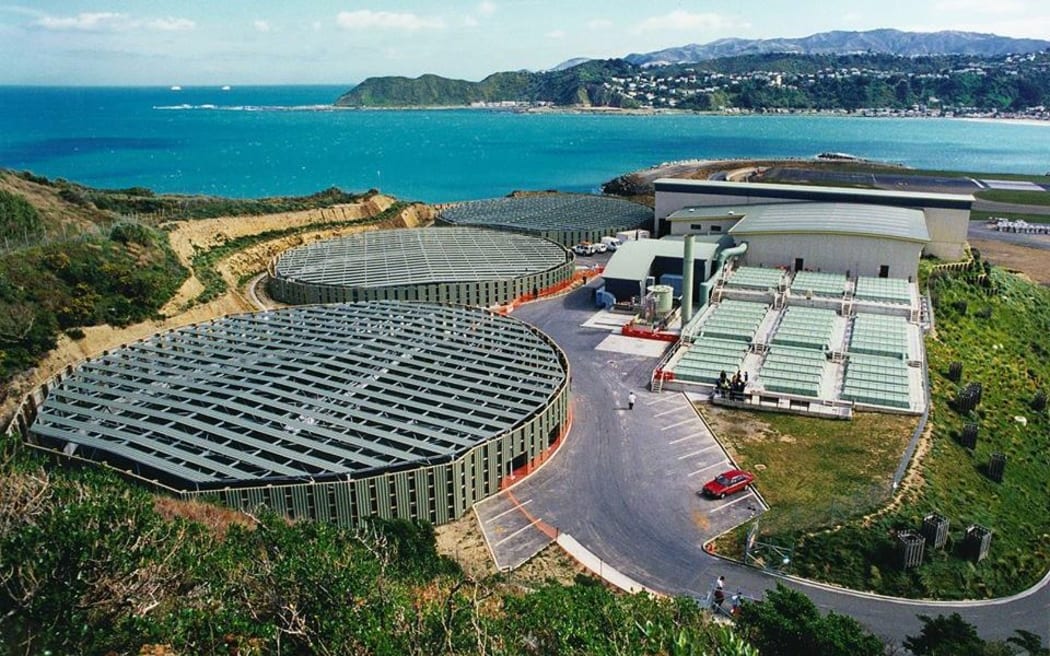

Water treatment is beyond the reach of most small towns. Photo: Wellington Water