A flawed 1961 study on methamphetamine's effect on pregnancy weight loss was the basis for the government's measures for contamination of state houses, a toxicologist says.

House contamination from methamphetamine, or P, has been in the news recently with the outgoing science adviser to the Prime Minister putting out a report at the end of May which essentially debunked the risks touted by the government.

So how did it all go so wrong?

Dr Leo Schep, toxicologist with the National Poisons Centre at the University of Otago, was part of the team that consulted on Sir Peter's report. He explains it's partly to do with the limited information available about exactly how toxic methamphetamine really is.

Using meth to lose weight during pregnancy: The original study

Photo: 123RF

Dr Schep tells Nights' Bryan Crump that New Zealand's standards were based on a US study from 1961 by J D Chapman*.

The study had - perhaps unbelievably to New Zealand's modern public - been trying to measure the weight-loss effects of methamphetamine on pregnant women.

"You had three groups and a control, a placebo, and they were given therapeutic doses of methamphetamine … in America you can still be prescribed methamphetamine for affecting obesity and things like ADHD."

Regardless of the potential ethical questions of the study's purpose, and the fact it was not even trying to measure toxicology in the first place, there were also a couple of problems with its methodology, Dr Schep says.

"This is what concerns me a little bit, they were given therapeutic doses of methamphetamine to control the weight that they were putting on, in addition to what is expected during their pregnancy.

"So they weighed the mothers, they were given the doses in a double-blind crossover study, one of the flaws in the study was they gave increasing doses for increased obesity ... so in other words they had already targeted doses to the mothers based on their weight.

Another problem with the study was the diet patients were on, he says, was not measured.

"So was the weight gain based on their diet, which wasn't controlled, or was the weight loss affected by the methamphetamine?

"Tests to it said 'at 5mg [per day] you found a significant decrease in weight in those people'. Right. So that became the gold standard, the line in the sand if you will.

"The trouble is, this is dealing with a therapeutic dose not a toxic dose … you could argue at those doses you're seeing toxicity, however in the study they measured their [electrocardiography] profiles which you would only see in large overdoses and they looked at side effects and they looked at clinical biochemistry parameters.

"And they found no significant difference between the various doses ... basically all the parameters they gave for toxicity."

Shifting the goalposts? Nah, science in action

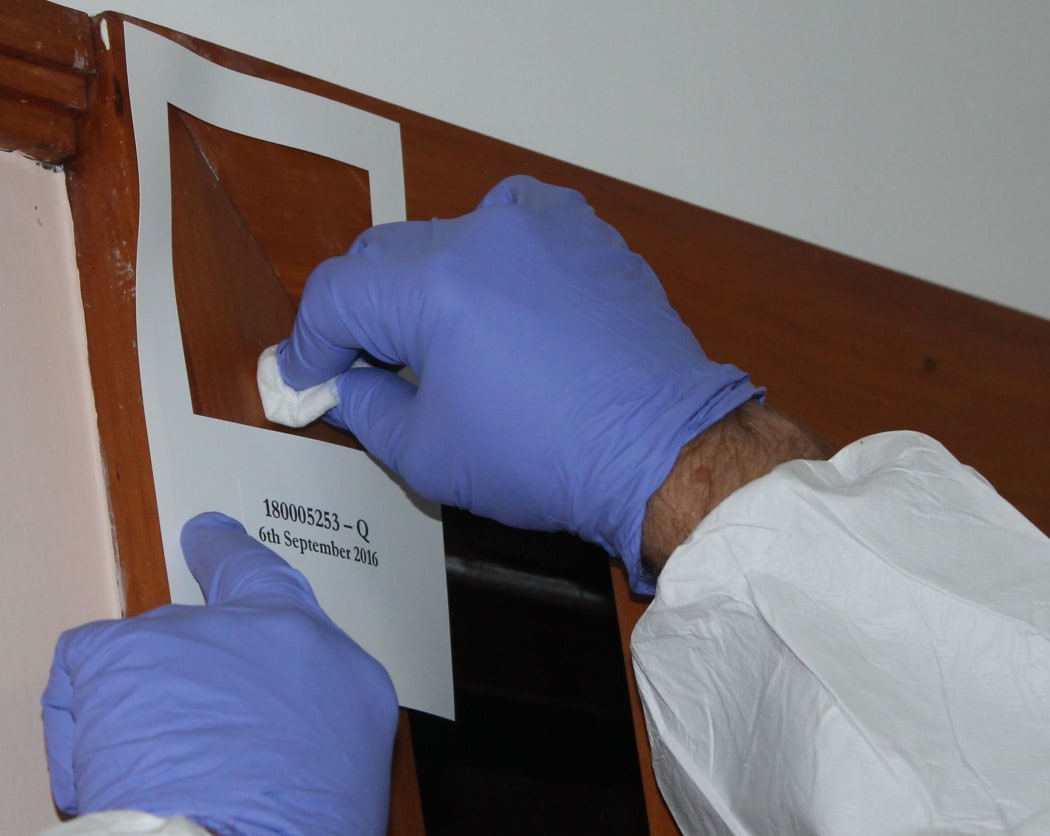

Testing a house for methamphetamine. Photo: Katy Gosset/RNZ

Dr Schep says he understands, however, why the New Zealand standard used the study in the first place - there were few other options.

"It has problems, but I can see why they used that paper and I wouldn't criticise them for that, because it is difficult to try to establish a dose that is of concern.

"That's very difficult, to establish a dose. It vexes toxicologists and they will argue till the return of Christ about given values for a given chemical, and that includes methamphetamine."

It was honest - albeit limited - science, Dr Schep says.

"It was conservative science, very conservative, and they came up with values that now Gluckman's office and the government are accepting that it's not the final word.

There was also the concern about setting a minimum standard - at the request of the government - when setting a benchmark too high could prove to be a health risk to the public.

"We have to be exceedingly cautious when it comes to defining a toxic dose that may be harmful to the most susceptible in our population, which is the young children and the pregnant mothers."

"That's science for you, it's moving, it's not set in concrete, we will change our values with time as more information comes."

Translation: From a flawed study to a minimum toxicity

So the study had its flaws, but it was something the scientists setting toxicity standards had to work from.

"What they did then was then apply a model to try and convert that dose to an acceptable dose on a wall," Dr Schep says.

"Because there is limited of amounts of information out there about [methamphetamine] toxicity, they latched onto that study and they said '5mg is the line in the sand of toxicity'.

"They said, 'we have to implement safety factors … we have to take into account things like variability between people'.

"They identified 5mg as the first dose that had a change in body weight … so we had to convert that from a low observation to no observation, and we put another [divide by] 10 in.

"Then they say 'well how robust is the study', well there are problems with the study - which I've highlighted - so they divided by three."

He said there were still further problems with the result however, as it still did not take into consideration the method of exposure.

"So you say 'OK If I'm exposed to 0.3μg per kilogram [body weight] - I'm allowed 0.3 based on that study' … what is the concentration of amount on a 100 centimetre squared surface on a wall that I can be exposed to without causing adverse effects?"

How toxic is too toxic?

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

So the standard is perhaps too conservative but the question then remains of what a safe minimum level should be.

He says methamphetamine contamination could potentially affect people in three ways.

"It's dermal contact with the walls, it's hand-to-mouth from what's exposed on your fingers to your mouth - particularly on children - and thirdly it's the residues that will then dissipate from the hard surface into the atmosphere and you're breathing it in."

However, he also says a PhD study investigated how much methamphetamine could be absorbed into the skin, which was tested by putting it under the tester's armpits, which found the amount that was absorbed was very low.

He couldn't say if a "common sense clean" would necessarily be enough to make a house safe, however.

"You'd need to talk to people in the industry."

The Gluckman report also noted there was a difference between houses where P had been smoked, and where it was manufactured.

"There is some evidence for adverse physiological and behavioural symptoms associated with third-hand exposure to former meth labs that used solvent-based production methods, but these symptoms mostly relate to the other toxic chemicals in the environment released during the manufacturing process, rather than to methamphetamine itself," it says.

Dr Schep says there are also social double standards at play.

"People smoke marijuana, they smoke cigarettes. Cigarettes, you know: nicotine is a neurotoxin."

He says the finding by Dr Nick Kim of Massey University, that some banknotes in circulation had similar levels of methamphetamine on them to the minimum standards, was accurate.

There were also aspects of that finding to bear in mind, though.

"If you were sitting there licking ... the banknotes, eight hours a day, then the risk would probably go up.

"It's not just the methamphetamine on the walls, it's the state of the house."

Politics and P: Dealing with the fallout

Housing Minister Phil Twyford Photo: RNZ / Richard Tindiller

Some of these problems were highlighted in Peter Gluckman's report, which was asked for after reports that meth contamination was costing the government millions.

Housing NZ had been using the minimum toxicity guidelines, which had already been questioned by toxicologists, to identify state houses that may prove a health risk to tenants, costing the government millions to clean up.

In an apparent attempt to recover some of those costs, it had also been prosecuting state house tenants over the contamination, not always successfully.

The Health Ministry itself had complained its guidelines were being misused, and there are also further costs to homeowners cleaning up contamination on their own dime, and the cost to government of having to continue housing state home tenants while its other housing stock was being cleaned.

After the release of the report, Housing Minister Phil Twyford has apologised over the actions of Housing NZ, saying it was because the opposition was too cowardly to do so itself.

Housing NZ chair Adrienne Young Cooper however, refused to step down over what Sir Peter called the "moral panic" over meth.

* Chapman JD. Control of weight gain in pregnancy, utilizing methamphetamine. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1961;60:993-7