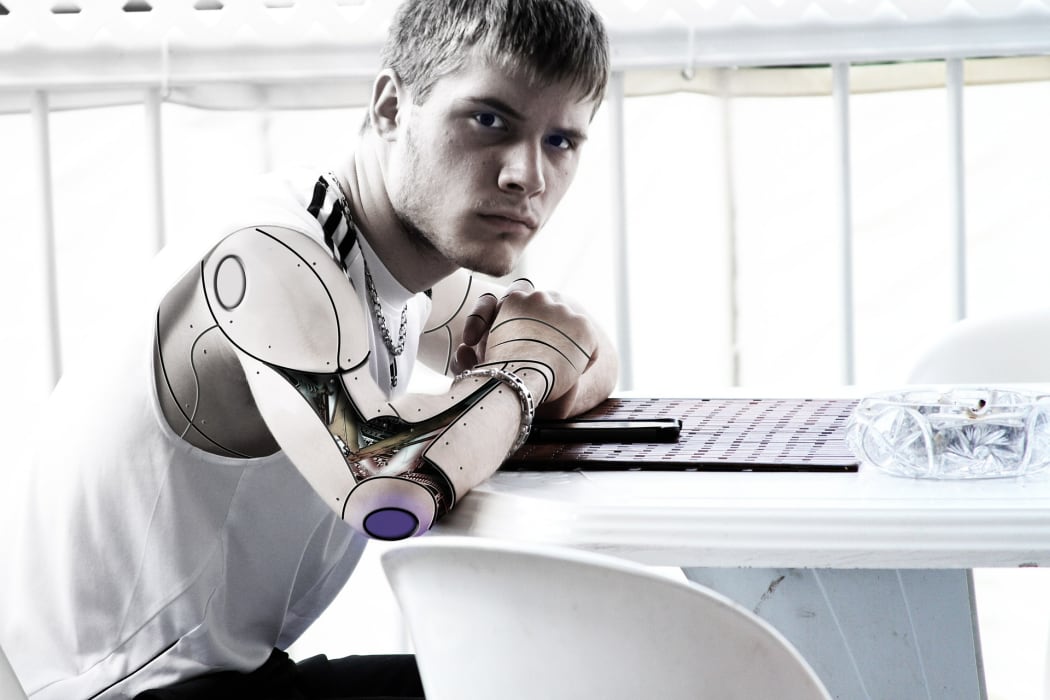

While artificial intelligence as we imagine it is still a while away, humans are cyborgs already, Ramez Naam says. Photo: Pixabay

Kathryn Ryan speaks to Ramez Naam, an award-winning author, futurist and computer scientist who contemplates a world where humans and our use of technology are significantly enhanced.

His fiction and non-fiction writing explores the impact of technology for enhancing humans and how it can change the world.

Ramez Naam's fiction book Nexus - the first in a trilogy - is about an experimental nano-drug that can link human minds together and how that changes the human condition and society.

Born in Egypt and raised in the US, he spent 13 years at Microsoft; he holds 19 patents on search engines, information retrieval, artificial intelligence and machine learning.

He is appearing at the Singularity U New Zealand Summit in Christchurch in November to talk about energy and industrial advances.

Read an edited excerpt from the interview below:

I’m interested in starting with the idea of how we imagine the future through fiction, because it has been the case that so much of the science-fiction of the 20th century has - whether exactly or slightly differently - effectively come to pass. Is this a way where you explore where things might get to in the future?

It is. I think when we write fiction, we explore not just the direction technology moves but also the motivations and passions of the people who use it, and that is so much what shapes our world.

Ramez Naam Photo: Supplied

It is hard to imagine where things may head and equally not so hard to imagine. Particularly this idea of the merging of man and machine, that we increasingly see a crossover between the organic human and how we continue to enhance, by the use of technology, our capabilities. By the mechanisms we have enhanced ourselves and our lives, even something as simple as education, we are already transhuman.

That’s right. We are cyborgs already. If you learn to read, it causes permanent changes to the structure of your brain for your entire life. If you have a cellphone and can connect to the internet and can transmit your thoughts immediately to someone on the other side of the planet, even like you and I are talking right now across the planet, to the ancient Greeks we would have been like Gods. In some ways technology keeps on enhancing us and we embrace it.

Equally, on the other side of the equation, if we look at the machines, we see the advance of artificial intelligence and we know we have machines that we call “smarter” because they are able to compute at ever increasing rates. But when we truly cross the threshold into artificial intelligence, what will the sea change be at that point?

I think we are quite distant from the way we imagine artificial intelligence in fiction. If you think of The Terminator or Skynet or the recent film Her, I don’t think that is anywhere on the horizon today. What is on the horizon is software that does individual specific tasks than we are. A self-driving car, where it can drive better than a human. But it has no idea of whether you want to go to the store or how in medicine we have software that can look at an x-ray or another scan or your blood test and do diagnosis of that to help doctors to maybe one day replace part of what they do. But it is still not full intelligence. It knows nothing about the weather or sports or philosophy. So I think that sort of A.I. is what we’ll have for a long time, and it will be our servant, not our master.

There is a step between the two because you’re not predicting sentients anytime soon. The most simple way I think of sentients is are you aware that you actually exist? That’s one possible, very simplistic approach. You’re not predicting that as a form of artificial intelligence any time soon. What is the barrier to it?

I think the barrier is that we don’t really know how to achieve it. A sentient creature that has feelings, is aware that it exists, has a very general knowledge of the world and can change its goals over time and that is a whole new branch of theoretical work. What actually gets worked on is not that, it’s things that have direct economic value.

With a self-driving automobile, everyone would like one. Once we get used to it and trust it, it can take time that we used to spend driving and it can give us leisure time or time to work, but you don’t want one that has opinions. You don’t want one that says, ‘I don’t want to go to that neighbourhood’, or ‘You haven’t washed me enough lately’.

So it’s actually counter-productive in many ways for us to add sentience to our software. We would rather just have things that accomplish the tasks we set to them.