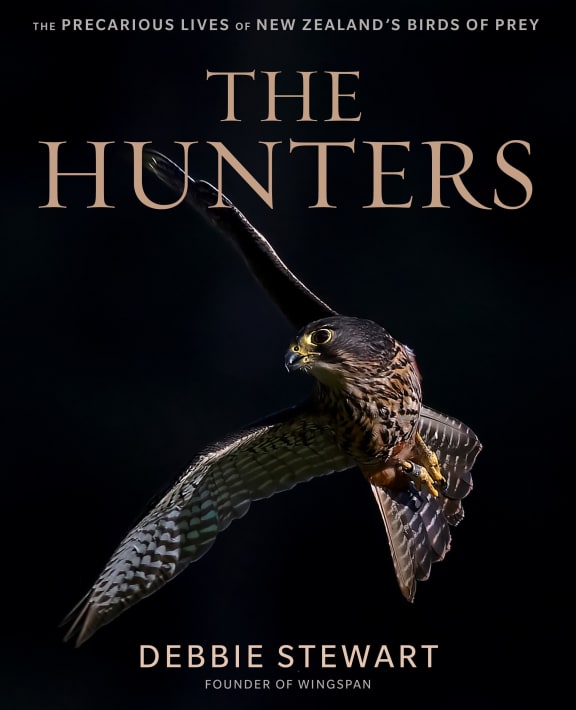

Debbie Stewart has spent decades dedicated to the New Zealand birds of prey.

A falconer for 40 years, she's is the founder of conservation and research organisation Wingspan.

Her book The Hunters: The Precarious Lives of New Zealand's Birds of Prey takes a close look at the raptors she describes as "attitude with altitude".

Stewart says she discovered her interest in wildlife while still “a little town kid”, when a great-aunt started sending her books on her birthday about naturalists such as Gerald Durrell and Joy Adamson.

“They inspired that interaction with nature,” she says. “I’ve come a long way from a 10-year-old trying to have a snail orphanage in my back yard.”

About 50 injured birds a year come to Wingspan’s Bird of Prey Centre, near Rotorua.

Many of them are the threatened New Zealand falcon or kārearea, which the centre is committed to conserving.

“Birds of prey are the barometers of the environment, they are the true indicator of a balanced ecology,” Stewart says.

The falcon are one of three remaining native birds of prey in New Zealand, along with the morepork / ruru and the swamp harrier / kāhu. Giant, moa-hunting Haast's eagles (pouākai) died out around 500 years ago and the Eyles' harriers, laughing owls and New Zealand owlet-nightjars are also extinct.

“Sadly for the falcons, many of them have injuries caused by deliberate shooting – which of course is illegal.”

They’re bold birds, she says, having evolved in a country without any natural predators or competitors.

“They’ll sit there and they’ll play, they make easy targets for people who don’t know or don’t care.”

Stewart says swamp harrier, which scavenge for roadkill, risk getting hit by cars, while ground-nesting ruru are vulnerable to predators.

Birds that can’t be restored to full health and released from the centre are paired in the hope they’ll breed. Their offspring are trained to hunt in the wild and released.

Stewart says raptors are valued near vineyards, horticultural blocks and forests, where they’re a form of natural biological control. “Often just their presence alone will deter other small birds from eating the grapes.”

In 2013 the centre also began releasing falcons in Rotorua city – the country’s first urban release of a threatened species.

“Birds we released six years ago are still frequenting the middle of the city, but they fly to a local forest each summer for breeding.”

Falcons have great aerobatic skill, flying at speeds in excess of 100kph and folding their wings to become like darts. And they’re incredible hunters; weighing 500g they’re capable of taking prey up to six times their body weight - though they can’t carry it away.

To fly this well - and hunt - they need to be “feather-perfect”, Stewart says. The centre uses feather extensions – not unlike hair extension – to repair damaged plumes until the birds moult and grow new feathers.

While most of their diet is introduced species, raptors will kill other native birds too. But it’s all about balance, Stewart says. “These birds have evolved together … No bird has ever gone extinct because of falcons predating on them.”