Mark Warren was just 24 years old, with a ticket to London and The Big OE in his pocket, when he got the call to take over the old family station in the steep hill country at Waipari in the Hawkes Bay.

"My father said, 'Oi! The manager's gone. All the staff are gone. You're going to have to take over...Make it snappy.' That was that. I went away for two weeks and came home...to face the music".

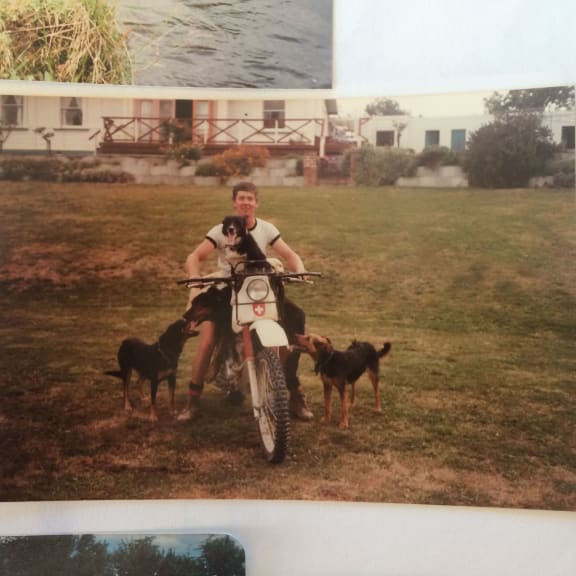

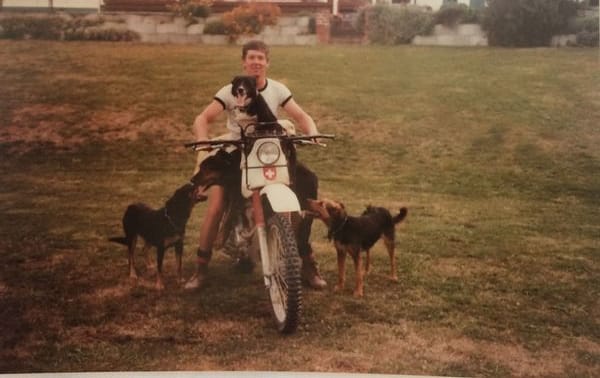

Photos from a life offroad and on the land

It was 1984, hot on the heels of the 1983 drought and weeks after the snap election that brought in New Zealand's fourth Labour Government under David Lange. Debt recovery, Rogernomics and the removal of government subsidies would follow, changing the face of farming forever.

"It was a mess. It was heading downhill very, very quickly", says Warren of the farm he took on single-handedly. A big farm is like "a huge wave that can crash on top of you."

"No other manager wanted to take it on".

He also inherited years of disrepair. Warren was the first family member to live on and manage the station since missionary Samuel Williams first took it over in the 1880s, and the descendant of generations of clergymen - not farmers. "Dad had no idea".

"My grandfather told me, 'if you don't save it, you've lost the family inheritance. So, yeah, a bit of pressure."

He got to work, ring-fencing the farm to reduce slippage and retain stock and dividing the farm. "I was just head down, arse up, trying to save it."

Mark Warren on his first visit to Waipari, his family station. Photo: Mark Warren

"I'm sure when I turned up people thought, 'who's this little smart-arse?"

Warren had to make some hard decisions and "stood on a few toes to get things done".

"I did have some doors slammed in my face by traditionalists." They appreciated the results later, he says.

Like every other farmer in the country, Warren had to absorb the impact of the new economy.

"Basically your income halved and your costs doubled 'cause the dollar dropped rapidly and we didn't have much to sell, but the thing that hurt the most was the interest rates. [New Zealand] went from a 14 percentage term mortgage rate to 22 or 23 percentage.

"The biggest business in town was paying off debt, trying to get money into the bank - not producing anything."

Lamb prices "just plummeted. I saw lambs go off the station in the '83 drought at $1 per head. Nowadays you could put two zeros behind that. Wool in those days was the saviour."

Warren focused on farmgate marketing, ensuring his stock found the best buyers. He positioned Waipari as a producer of export quality lamb. He would also get into forestry early. "As soon as I got my head anywhere near the surface I'd buy more shares in the farming station off the cousins and aunts and district relations."

Never having lived on a farm, he did benefit from his experience working other peoples' farms in the South Island hills and High Country in his teens and of "being tutored by 20 or 30 different farmers by the time I was in my early 20s. That was of huge benefit... I did have some great mentors."

By 1990, his hard work had paid off. Waipari had "turned the corner". Its success has continued ever since.

Waipari Station from above Photo: Lee Warren

In 1992, Warren won the Hawke's Bay Farmer of the Year competition - one of the youngest ever to do so.

"That was a pretty major goal achieved…[and] I'd set myself some pretty lofty goals."

His pride in this achievement comes from what he did with what he was given. "People think I inherited a farm. I didn't inherit a farm, I inherited a whole lot of debt. I inherited an opportunity."

Warren is equally well known as a 4WD expert - a lifelong passion. He grew up obsessed with vehicles: Land Rovers, council tip trucks, bulldozers, hill-country tractors and snow ploughs. If it had four wheels, he says, it warranted his attention.

He was 4 years old when he first got behind the wheel of a car, with his friend Huey Chapman in Geraldine.

"His Dad used to help us drive his '37 Chev truck. One of us would stand on the seat and work the steering wheel, one would lie on the floor and work the clutch and gears. It was a team effort. I was pretty capable of driving a vehicle of my own by age 6."

This led to work as a "grease monkey" and ski field operator, gaining valuable off-road experience.

Four wheel rally driving is his passion, and he spend years rallying in a purpose built Toyota Land Cruiser. "I was lucky to stop at the top of my game and I made doubly sure I won a couple of national titles." Later he was approached by Mazda to test-drive their Bounty utes and went on to train other drivers.

These days he has turned this into a career as a four wheel drive expert. He's taught thousands of people to survive driving in tough conditions in snow, ice and mud.

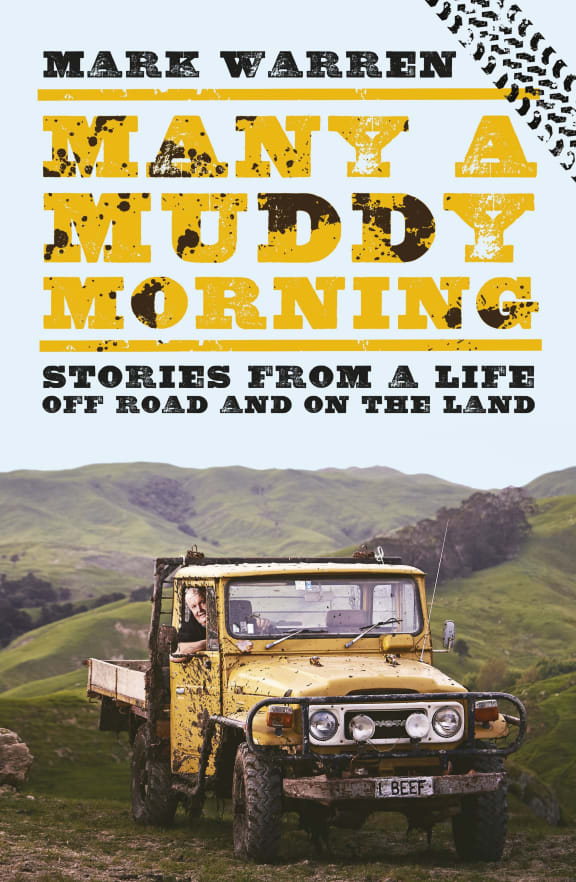

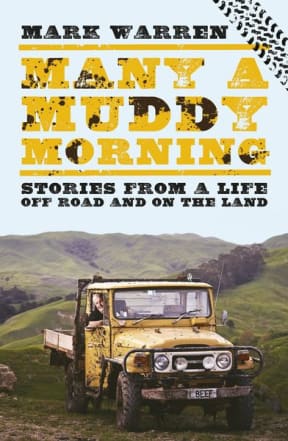

Warren also overcame severe dyslexia to write a book about his life, Many a Muddy Morning: Stories From a Life Offroad and on the Land, out this month.

Cover of Many a Muddy Morning by Mark Warren Photo: HarperCollins

"I can hardly read my own writing!" he says. "It took me a year to write and four years for the editors to get it into a format anyone else could understand."

Along the way, Warren has "hit the wall sometimes" and learned the importance for farmers of maintaining what his friend Doug Avery calls "the top paddock" - their mental health.

"It's a really, really big issue and a serious one. It's hard to drain the swamp when you're up to your arse in alligators."

"The problem with me was that I tended to maintain my tractor better than I maintained myself."

He now knows to surround himself with people he can call on when he is down and is donating his book royalties to Farmstrong, which helps farmers develop skills and resilience to cope with the stresses of farm life.

Reflecting on his success, Warren says "I had an opportunity. I was very, very lucky."

His dyslexia has been an advantage, helping him 'think outside the square" and enabling him to see opportunities other couldn't see. He recommends an open mind - "zig when others zag" - when young farmers ask him for advice.

"Experience is the thing you get the split second after you need it", he says.