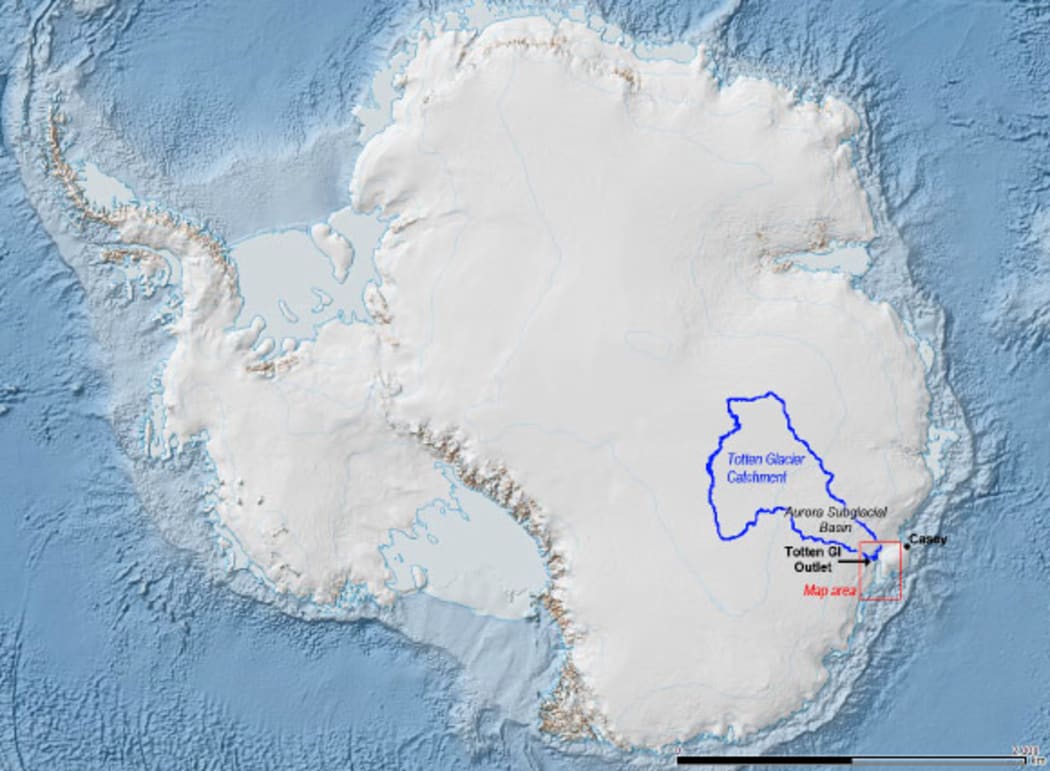

The large Totten Glacier drains a major portion of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Photo: Esmee van Wijk / CSIRO

The West Antarctic ice sheet, the smaller of Antarctica’s two ice sheets, has long been thought of as fragile and at risk of melting as the oceans warm.

Steve Rintoul on board the Aurora Australis during the expedition to the Totten Glacier. Photo: Steve Rintoul

But Steve Rintoul, an Australian oceanographer who recently led an expedition to one of the continent’s largest glaciers, says the larger East Antarctic Ice Sheet is not the sleeping giant scientists had hoped. Instead it is just as sensitive to warming waters and could contribute significantly to future sea level rise.

“Antarctica holds so much ice that if all of it melted it would raise sea levels by 58 metres. We need to know what’s happening in Antarctica, because even the loss of a small amount of Antarctic ice could change sea levels by a significant amount.”

Dr Rintoul, from the Australian Climate and Environment Cooperative Research Centre in Hobart, led a voyage that became the first to sample the ocean alongside the Totten Glacier, which drains a large part of east Antarctica.

Until this voyage, no oceanographic measurements had been made within 50 kilometres of this glacier, one of the world’s largest and least understood glacial systems that holds enough water to raise sea levels by more than three metres.

The Totten Glacier catchment is estimated to contain enough ice to raise sea levels by at least 3.5 metres. Photo: Jamin Greenbaum / Australian Antarctic Division

Satellite measurements show that the Totten has been thinning faster than other glaciers in east Antarctica and Dr Rintoul says the ocean samples indicate that it is being melted by the oceans from below.

“What we found is that warm water does indeed reach the glacier. The ocean is quite deep in front of the glacier and that’s important because those deep channels allow warm water to reach the cavity.”

Ocean sampling instruments being lowered during the voyage. Photo: Steve Rintoul

The expedition found a deep trough, about 1100 metres deep, “right in front of the nose of the Totten”, he says.

“We measured ocean temperatures and found that there is, at the bottom in this trough, a lens of relatively warm water. That water is several degrees warmer than would be required to melt ice, so there’s plenty of heat there to melt ice.”

An even bigger surprise was the discovery that warm water was covering the entire continental shelf around this part of East Antarctica.

“I think what’s important about these results is that there is a strong case now that east Antarctica is not immune to changes in the ocean and that east Antarctica is likely to make more of a contribution to future sea level rise than we thought,” says Dr Rintoul.

So far, the oceans have taken up 93 per cent of the warming caused by increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The warming alone has already led to rising sea levels, because warmer water expands. But another consequence is that the warming seas have begun to melt Antarctic ice from below.

This has so far been most significant in West Antarctica, where the melting of some glaciers is now unstoppable, according to reports from NASA last year.

East Antarctica was considered more stable, but Dr Rintoul says three threads of evidence have challenged this view.

Satellite data clearly shows that East Antarctica is thinning in some parts. Measurements from aircraft that carried ice-penetrating radar instruments also show that the ice in east Antarctica is partly grounded below sea level, which makes it more vulnerable to ocean-driven melting. Lastly, Dr Rintoul says, there is evidence that past sea levels were about 20 metres higher than today during a period some three million years ago, known as the Piocene.

This was the last time in Earth’s history when carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere were similar to today, and temperatures were two to three degrees higher. Dr Rintoul says even if both the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets had melted then, that would still not account for the 20 metres in sea level rise, suggesting that parts of east Antarctica had also disappeared.

“The single greatest uncertainty is projections of future sea level rise has been the behaviour of the ice sheets on Greenland and in Antarctica. All of this suggests that Antarctica will make a larger contribution to future sea level rise than we thought."

Steve Rintoul is in New Zealand this week to deliver the annual ST Lee lecture in Antarctic science.