By Alison Ballance

“For the last few years we’ve seen quite a few rather bald and mangy looking kakariki, and we’ve discovered it’s a skin mite. The mite is microscopic, and it burrows around the feather follicle and pushes the feathers out.”

Emma Wells, bird keeper, Auckland Zoo

Studying kakariki on Tiritiri Matangi Island

“The reality is we seeing more and more disease in wildlife. Because of the pressures wildlife is under animals are increasingly stressed and they’re succumbing to things that historically they might have been able to fight off.”

Dr Bethany Jackson, wildlife vet, Murdoch University.

A tiny skin mite causes mange and feather loss in more than half of the adult kakariki on Tiritiri Matangi Island. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Kakariki or red-crowned parakeets on Tiritiri Matangi Island, an open sanctuary in the Hauraki Gulf, have a problem. Many of them are losing feathers, and in the worst cases birds are becoming quite bald.

The culprit was identified as a mange mite by Australian wildlife vet, Dr Bethany Jackson, from Murdoch University. A few years ago Bethany investigated the problem as part of the PhD research, and since then she has worked with Auckland Zoo in an ongoing disease screening programme on the island.

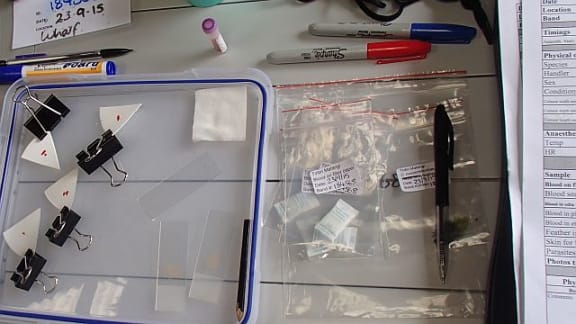

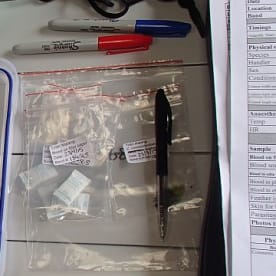

Every spring a team visits the island to catch kakariki in mist nets, and assess their health status. The birds are banded, measured and weighed, blood samples are collected for disease screening, and feather loss is estimated. Over the week the zoo staff and volunteers are on the island they usually manage to sample about 70 birds. This spring more than half of the birds studied had mange.

Auckland Zoo keepers Emma Wells and Nat Sullivan also carry out a nesting study, following breeding success in fifty kakariki nests.

“What we want to know is how the mange is related to weather patterns and to food availability,” says Emma. “We also want to know if it’s causing issues with breeding. Last year, for instance we had a really low chick survival, with no survivors.”

Emma says that it seemed this low chick survival was related to poor food availability, and that the mange is worse during a poor food year.

The team take photographs of each bird, and by comparing photos of birds that have been caught more than once, over several years, there is evidence that some birds can recover from a bad case of mange.

Bethany says that the mite affects adult birds, but not chicks.

“We also know that kakariki on Little Barrier Island carry the mites, too, although they were looking normal when we sampled them,” says Bethany. “So we suspect this mite could be quite widespread in parakeets in New Zealand.”

Bethany says that it’s important to establish baseline disease surveillance for animals to set a benchmark for what’s ‘normal’.

“While disease is something that has always been part of wildlife ecology, the rate of change in terms of habitat change, climate change means wildlife is under increasing pressure from all directions, including predators,” says Bethany. “And really disease is just another threat we want to be keeping tabs on, and seeing if there’s something new coming into the country. And the reality is we seeing more and more disease in wildlife.”

Tasmanian devil facial tumour, chytrid fungus in frogs and a new fungus infecting salamanders are example of recent disease outbreaks, and Bethany says the growing international trade in wildlife increases the chances of diseases spreading.

Last year Our Changing World joined Auckland Zoo as they released captive-bred wetapunga, or giant weta, on Tiritiri Matangi Island.