There’s only four humans who have consecutively spent more than a year in space and the shortest trip ever possible to Mars is approximately two years.

Mathias Basner, University of Pennsylvania

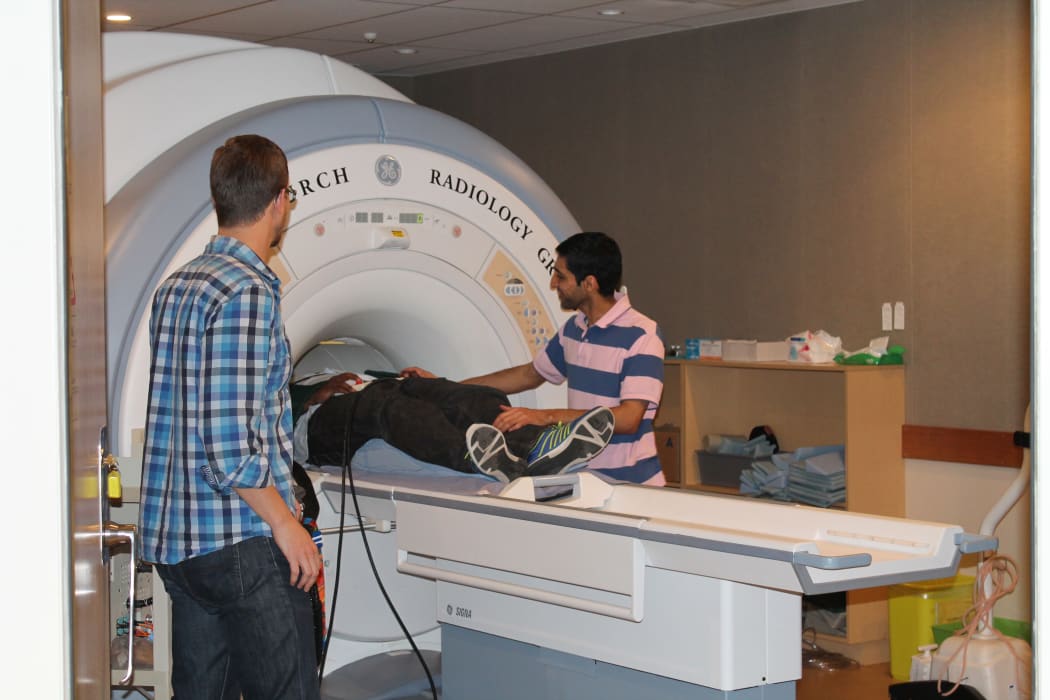

Christchurch collaborators are helping to run the scans. Mustafa Almuqbel prepares a research team member for his MRI. Tracy Melzer of the New Zealand Brain Institute is in the foreground. Photo: Katy Gosset

For many space is still the final frontier.

And when it comes to a mission to Mars, everyone wants to know what's out there. But NASA also wants to know what's within. Specifically, what's within the brains of its astronauts and what might be changing while they're taking part in long space missions.

Mathias Basner, of the University of Pennsylvania, leads the research. Photo: Katy Gosset

Mathias Basner, an associate professor of sleep and chronobiology at the University of Pennsylvania says currently, the neurological impact of long duration space travel is still unknown.

"There’s only four humans who have consecutively spent more than a year in space and the shortest trip ever possible to Mars is approximately two years.”

As part of his research, co-funded by NASA and the German Aerospace Center, his team has been scanning the brains of individuals living in what are known as "analogue settings".

These are other extreme and isolated environments, including Antarctica, that mimic the conditions astronauts might experience in space. He says the team is looking at whether exposure to such environments causes neuro-structural changes. "Does anything change with brain structure and function when people are in this isolated, confined and extreme environment for a prolonged period of time."

Mathias Basner says the results will be relevant to NASA's plans for Mars.

People who will travel to Mars and back will experience the same thing. They will be confined to a very closed space, spent together the whole time with only a few people. And it's, of course, you know, a very extreme environment and very hostile and dangerous to humans.

The Christchurch Connection

Mathias Basner's team recently arrived in Christchurch where, in collaboration with the New Zealand Brain Research Institute, they prepared protocols to scan the brains of crew who have wintered in Antarctica. The 13 French and Italian staff from the Concordia Research Station will all be tested immediately after returning from the ice throughout November and December.

Ruben Gur and Christchurch PhD student, Mustafa Almuqbel, view images from the MRI scanner. Photo: Katy Gosset

He says a collaborator, Alexander Stahn from the Centre for Space Medicine in Berlin, has already conducted similar tests on crew at the German Neumayer Station in Antarctica.

He says these showed that the hippocampus region of the brain, which is important for both memory formation and visual/spatial orientation, actually shrinks during the Antarctica winter.

So the idea there is, if you're always in the same environment, no variety, always with the same people, and then also the psychological stress associated with living in this isolated, confined and extreme environment, that that actually is the cause for these structural changes in the hippocampus.

He says those scans were done before and after the winter period in Antarctica. However, this research will add a further test, scanning the crew members before, immediately after their return and then a further six months later to assess whether the hippocampus recovers.

He says that’s why the collaboration with Christchurch researchers is important, enabling the crew to be tested straight after leaving the ice. “We want to get them as soon as possible, when they’re leaving this environment, because we don’t know how long these changes are going to last.”

Tracy Melzer, the MRI research manager at the New Zealand Brain Research Institute, says his role is simply running the scans and ensuring the project is a success. But he hopes further collaboration will be possible. He says New Zealand punches well above its weight in brain research and he hopes that local investigators will be involved in some of the project's future analysis.