Engineers are creating miniature rivers and beaches in the Water Engineering Laboratory at the University of Auckland, to study how water flows and better understand how floods and tsunamis behave.

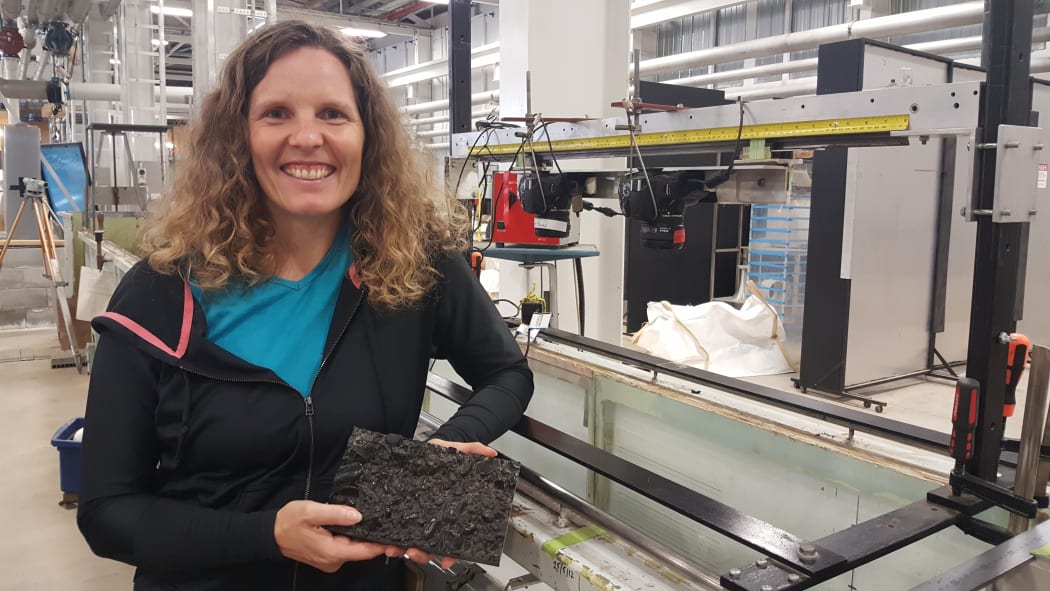

Engineer Heide Friedrich. She is holding a piece of moulded 'riverbed' covered in small pebbles. Water flowing above this rough riverbed is photographed and videoed using the cameras mounted above the flume. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Subscribe to Our Changing World for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

Engineers model what happens in streams and rivers using a flume, which is a long tank along which water flows. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Dr Heide Friedrich is an environmental engineer at the University of Auckland. She specialises in studying the behaviour and impact of water in rivers and streams – which is difficult to do because water is transparent.

“It’s about making the invisible visible,” says Heide.

She does this by creating simplified streams and rivers, using flume tanks.

“What we're doing," says Heide, "is bringing the river or ocean into the laboratory."

The Water Engineering Laboratory is impressive. It’s the size of a large warehouse, half a rugby field in length. There is a big underfloor reservoir to hold water that can be pumped around the many large pipes to various-sized flumes or water channels.

The biggest feature in the room is a steel flume that’s one and a half metres wide and over 40 metres long – it is one of the largest flumes in the southern hemisphere.

The key feature of the flumes is that they are about moving water.

“If you have the water not moving, not dynamic, there’s no life in there – it’s dead,” says Heide.

The researchers are able to get water moving really fast if they want to - water flow in some of the flumes can be more than a thousand litres a second.

The Water Engineering Laboratory at the University of Auckland contains a number of flumes, including one that is 40 metres long. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

To understand how water flows along different kinds of river beds, engineers create realistic scaled-down versions of the real thing in the lab. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

But as big as the flumes are and as fast as the water is flowing, these are much smaller than natural streams and rivers. The trick is to downsize, but keep conditions realistic.

“Scaling is really important,” says Heide, who points out that the flumes can’t be infinitely small “as you are going to lose the specifications or characteristics you are studying.”

The value of measuring water in a flume is that it can be completely controlled – there is none of the chaos and potential danger of trying to measure a river in flood, for example.

“By controlling it we always reduce the system,” says Heide.

“That’s the challenge between science and engineering. Science has a holistic approach, whereas in engineering we are reductionist. We reduce it so much so we can really identify what is force, and what is action and reaction.”

Heide and her colleagues are studying more than just water. Think of waves at a beach – they usually stir up lots of sand. A river is moving sediment, leaves, branches, and – during a flood – maybe entire trees.

So the water engineering laboratory has sediment pumps as well as water pumps, and dotted around the room are containers of different-sized materials, ranging from fine sand to coarse pebbles and even larger rocks.

To make close observations about what is happening in each flume, the researchers increasingly use cameras mounted above the flume.

Heide is interested in teasing out how different kinds of rivers and importantly river beds, respond to different amounts of water, such as during a big flood. Engineers then use this information to design better bridges and flood banks.