“When you’re thrown into some place that’s very foreign and very different, you get distilled down to your very essence and you understand your own country and culture with a clarity that’s not otherwise possible."

Photo: Supplied

Writer and psychology professor Andrew Solomon is fascinated with places in major transformation – cultural, political and spiritual.

He talks with Wallace Chapman about what he's learned, traveling 7 continents over 25 years.

Salman Rushdie calls Andrew Solomon's latest book Far and Away: Reporting from the Brink of Change“a beautiful book" and "a portrait of our world”.

On travel:

Andrew Solomon: When you’re thrown into some place that’s very foreign and very different, you get distilled down to your very essence and you understand your own country and culture with a clarity that’s not otherwise possible.

I started, as most people do, as a tourist, which involves going and looking at it. But I think I was always an open-minded tourist. I had the sense that when I went to these different places and saw them that I had to try and understand what they were like and not simply look at them as a way of affirming how happy I was to be in my own culture.

But over the years as I began writing and began having these serious encounters with other places, I wanted to become a traveller and see if I could enter into the reality of the places I was going.

In the end, I did a lot of in-depth reporting and I went into war zones and I did all of these other things that feel quite daredevil in retrospect. But I think you can start quite early on to make yourself a traveller instead of a tourist – and I tried very hard to do that.

On Greenland:

Kangerlussuaq in Western Greenland Photo: Greenland Travel

Andrew Solomon: The landscape of Greenland was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. The quality of the sun refracting through the ice in the Kangerlussuaq ice field will stay with me forever. It was like being inside the most beautiful piece of diamond jewellery that you can imagine.

But I was also very moved by the life of the Inuit. One of them said to me, memorably, “I know that where you came from you built great civilisations and great governments and came up with remarkable works of art, but us, in this environment, for thousands of years we’ve survived.” And I was tempted to say that that was the greater accomplishment.

And I found people very receptive, they were very open. I was trying to work on the subject of depression. They aren’t a particularly verbally communicative people in general, but they made an enormous effort to talk to me about their experience. It felt like a much more intimate and embracing place than I would ever have guessed or imagined.

In a typical Greenlandic winter everybody used to be stuck in an igloo. If you’ve ever been in an igloo, you cannot imagine how tiny they are. The way people kept warm is they were all physically lying on top of one another. The only other source of warmth or light would be a seal fat lamp, which does not throw off a great deal of warmth or light. Now they live mostly in Danish prefab housing, but even so, because there’s no natural source of fuel, their houses are tiny. If you’re in a situation like that and you’re very emotional and you have big arguments and dramatic things happen, it’s deadly to go outside.

It’s so cold and so dark that you’d die after you’d been outside for ten minutes. So if you have an argument with someone you have to sit there and continue to stare at the person you just had an argument with. And you will find if you undertake doing that, that it’s better or easier or preferable to restrain some of your emotionally outgoing nature in favour of relative silence, because relative silence creates less friction in that constrained situation. So [the incidence of depression there], it’s a result of the climate but it’s not a response to the climate itself. It’s a response to those circumstances.

On meeting the Cambodian humanitarian Phaly Nuon:

Phaly Nuon Photo: Courtesy of Kelly Wetherington

Andrew Solomon: During the Khmer Rouge period, she managed – unlike most educated people in Cambodia – to remain alive, and how she remained alive, it’s a long story. She had children with her. Her eldest daughter was raped in front of her and then killed while she was forced to watch. Her baby died because she was malnourished and couldn’t produce breast milk. And she had one other child who lived. And she kept going for that one other child. Her husband had been taken away.

She got through the Khmer Rouge period and then she was in a resettlement camp. And in that resettlement camp she observed that there were many women who had somehow survived the horrors of the Khmer Rouge but who were sitting in front of their tents barely able to move and failing to take care of their own children.

And she went to the people who were running the camps – she was educated and could speak languages so she could communicate readily – and said ‘What are you going to do about this?’ And the people who were running the camps said ‘We have our hands full trying to deal with infectious disease, we can’t do anything about it’.

So she undertook to figure out what she could do for these women. She said she realised that she had to teach them in three stages. She said, first I would try to teach them to forget. I would try to teach them to forget by crowding their minds with other new things to talk about, not that they would ever really forget what happened but that it wouldn’t occupy their whole minds. And after I had taught them to forget I would teach them to work. Some would never do more than clean houses, some had a gift for crafts. I found something for each of them to do that had some meaning for them. And then after I had taught them that, I taught them to perform manicures and pedicures. And I said ‘I beg your pardon?’

And she said ‘The thing people had most lost in the Khmer Rouge period when so many rose up against so many was the ability to trust anyone. These women hadn’t had a chance to feel beautiful in five years. And I filled my hut with steam and I invited them in and I handed them these sharp implements. And bit by bit they allowed one another to use these sharp implements’ she said.

‘And as they did that, as that barrier that you could never make yourself vulnerable to another person began to fall, they began to speak to one another, and they began to remember what it was like to trust somebody. And when I was finished I would tell them that those are not there separate things – to forget, to work and to trust – but three parts of a single way of being in the world. And when they understood that they were ready to go out into the world again’.

On his 2002 visit to Afghanistan:

Andrew Solomon: I went with my heart in my throat thinking it was going to be a punishing but fascinating experience that would leave me with a story to tell. I got there and I loved Afghanistan. I loved the Afghan people, I loved the things that I saw. I wrote about the resurgence of culture following the fall of the Taliban. It was really about how a society can be reborn in the wake of oppression. And there was a moment that’s always struck with me particularly that doesn’t feature as large in the story as it might.

I had wanted to buy a fur hat, and I’d bought one of those little fur hats that you may have seen - all of the Afghan leaders and tribal people wear them. And I was walking back through a crowded market at a time when very few Westerners would walk through such a marke.t My translator had said “It’s perfectly safe. We can walk straight through here.” And as we were walking along he said to me ‘Put on the hat’.

And I said 'Oh. I think it looks a bit silly and a little bit affected – you know, foreigners trying to go native’. He said, ‘No, put on the hat’. I said ‘I really don’t think so’. He said ‘Please put on the hat’. I said okay, and I put on the hat. And all around me, suddenly, everyone burst into applause. I couldn’t think what was going on, and I looked around. One of them stepped forward and gave me a hug and said ‘You are a foreigner but you are wearing a proper Afghan hat in the proper Afghan way. You are here within our culture. We want you to know that you are welcome here.’

On lessons travels has taught him:

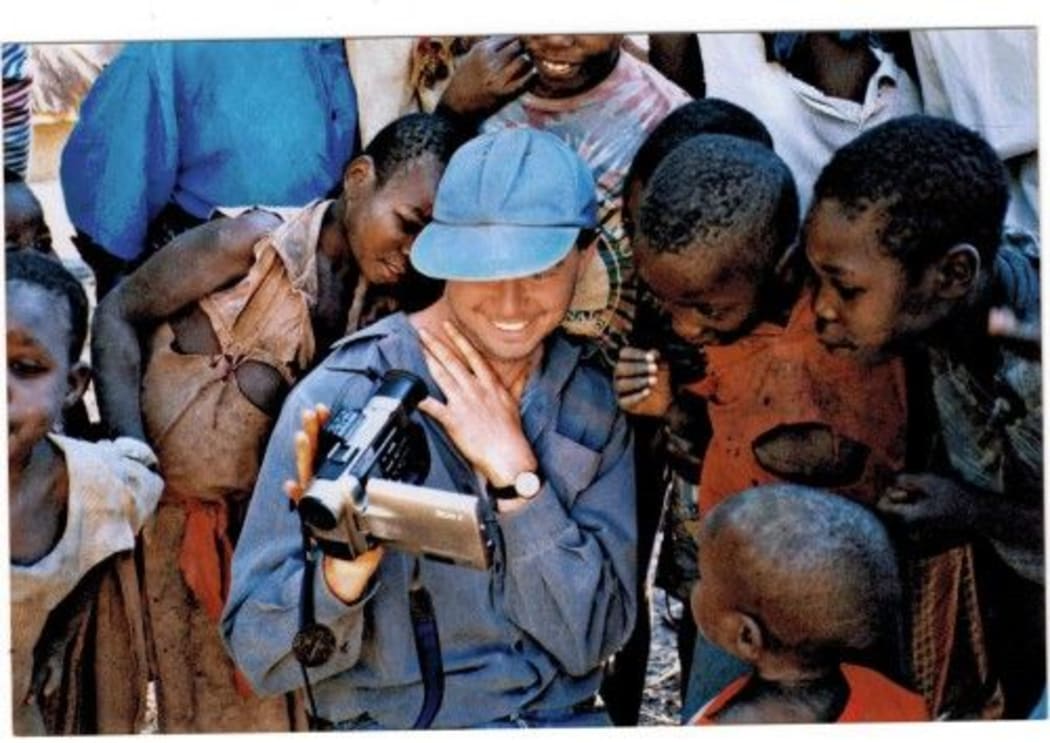

Andrew Solomon in Zambia in 1997 Photo: Luca Trovato (Courtesy of Andrew Solomon)

Andrew Solomon: The first thing I’ve learned is that places go through phases of hope and those phases of hope are immensely beautiful. And sometimes that hope is fully realised and the places where it has arisen move on to freedom and democracy. But frequently you need to have hope occur over and over and over again before that hope is realised. And that process in which peoples’ hopes rise up and they’re dashed and they hope again is itself valuable. Hope is valuable even if it gets disappointed. It stays with people forever and they hold on to it.

It’s very difficult to hate anyone whose story you know. And it’s very difficult to sustain a profound enmity with an entire nation if you’ve actually really engaged with it and allowed it to engage with you. So while I think hope is often disappointed and the world is full of terrible governments and evil and repressive regimes, I think if you can get people to interact with other people, you will find there’s actually a basis for much more hope about diplomatic process than citizens ordinarily have.

Watch/listen to Andrew Solomon’s TED Talks