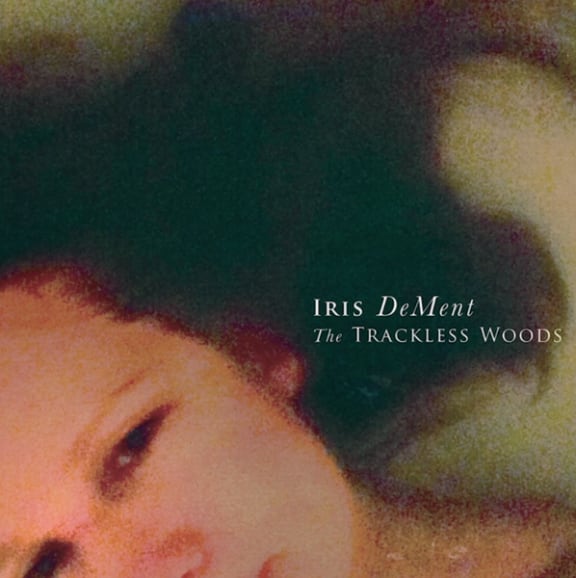

Nick Bollinger reviews a new album by American roots icon Iris DeMent that has its roots in 20th century Russia.

Iris DeMent makes some of the most authentically southern music you'll hear. Her voice, her songs and her country gospel piano all point directly to her Arkansas roots. But her new record has a very different set of roots, geographically and historically. All seventeen of the songs on The Trackless Woods take their lyrics from poems by the twentieth century Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

Over the almost quarter-century since her extraordinary debut album Infamous Angel, one of the consistent features of her music has been the personal nature of her lyrics, which draw on the specifics of her life story, describing places and people, sometimes even naming them. Parents, husbands and several of her thirteen brothers and sisters have appeared in various DeMent songs which, taken as a whole, create a picture of where she comes from; a large family of farmers and labourers from the border of Arkansas and Missouri, displaced to California when hard times hit the farm. But these new compositions take her not just inside someone else's world, but one that - outwardly, at least - seems very different from her own. Born in 1889 of aristocratic roots, and by her own account a distant descendant of Genghis Khan, Anna Akhmatova grew up in St. Petersburg where in the early years of the twentieth century she became an important figure in the city's bohemian poetry scene. Initially inspired by the Symbolists, she gradually moved towards a style rooted in a more concrete reality. It's a different reality from DeMent's, but there's a plainness and economy of language that the two writers share, and which is one reason Akhmatova's words flow from DeMent with such apparent ease.

For all their basis in the day-to-day particulars of her own life, DeMent's songs have always had an existential dimension to them. When they describe forms of suffering, as they often do, the very specific nature of that suffering - the loss, say, of a parent or sibling - is surprisingly universal. The particulars of Akhmatova's suffering were undoubtedly different from DeMent's. The years immediately following the revolution had seen the flowering of the Russian avant-garde, in which the poet thrived and produced some of her best-known work. But renaissance soon gave way to repression and from 1925 to 1940 Akhmatova's books were officially banned, while many of her friends and colleagues, including her son, were forced into labour camps and worse by the Stalinist regime. And the depth of her grief is measured in the restrained yet ultimately devastating sense of loss in lyrics like the one called 'The Last Toast'.

The songs, DeMent says, came to her at the piano, a book of translations of Akhmatova's poems on the music stand, often turned to a random page. So particular was the environment to the songs' creation that DeMent decided she had to record the album exactly where she had composed it, bringing studio equipment and musicians into her Iowa home. And the recording certainly captures that intimacy. The other players and singers are subtle. They include legendary names like guitarists Leo Kottke and Richard Bennett, who co-produced the album with DeMent. But for much of the record one hardly notices they are there.

I've kept looking for the reasons The Trackless Woods works so well when the worlds it brings together - those of a Russian poet and an Arkansas rustic - seem so far apart. In addition to the things I've identified, there's the fact that the poet's rhythms are very song-like and the translations DeMent has worked from - mostly by Babbette Deutsche - gently highlight her use of rhyme. DeMent has even said she believes Akhmatova must have conceived some of these poems as songs.

There is also the shared sense of place. It is said that Akhmatova refused to emigrate, despite enduring great hardships, as she believed a poet could only sustain their art in their native country. But perhaps the most crucial connection for DeMent is the most personal one. She and her husband, the singer-songwriter Greg Brown, have a daughter Dasha, who they adopted from Russia in 2005. DeMent says that in gaining a family her daughter had to give up the land of her birth, and that in setting these poems she has tried to give Dasha back some of the country she has lost. What makes that gift even more poignant is that so many of these lyrics, written against a background of purges and repression, mourn the loss of that country as well.

Songs: 'Like A White Stone', 'Broad Gold', 'From The Oriental Notebook', 'The Last Toast', 'Listening To Singing', 'And This You Call Work', 'Not With Deserters'.