Language is very fluid, it's evolving through space and time. I prefer to think that there is no such thing as "English, German or French", rather there is inter-language. - Professor Jonathan Stalling

American Associate Professor of English at the University of Oklahoma, Jonathan Stalling has created Sino-English, a new alphabet for 350 million Chinese across the globe that may be struggling to learn English. As a specialist in Chinese-English poetry and language Dr. Stalling is utilising ancient poetics to help Chinese speakers to learn spoken English more efficiently. His invention has world-wide applications.

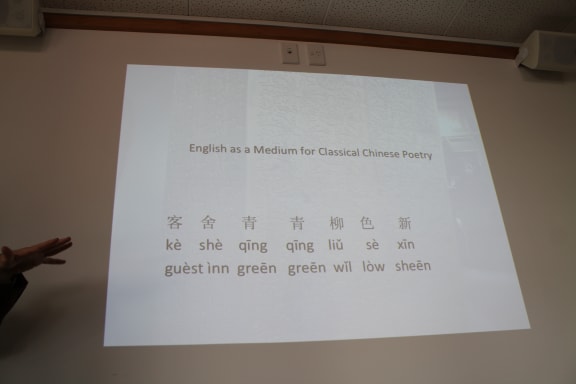

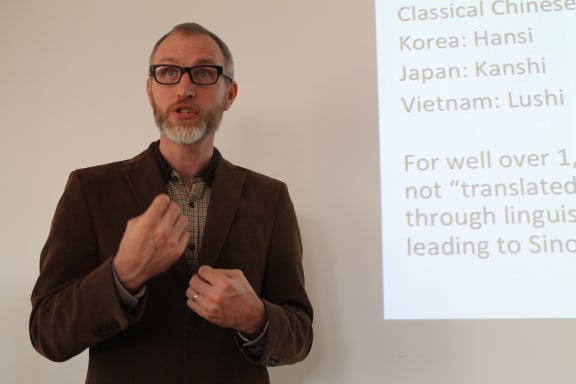

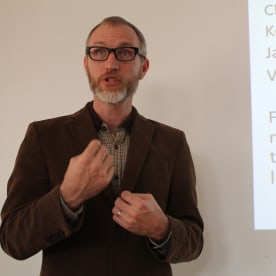

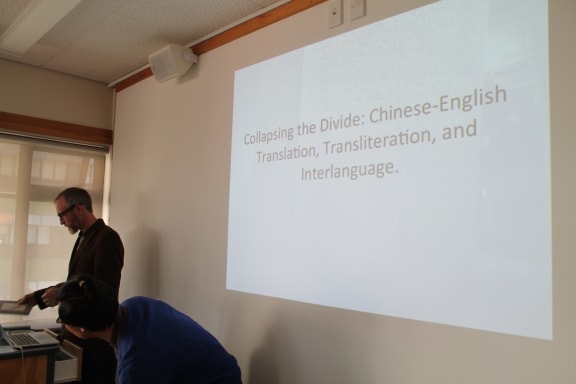

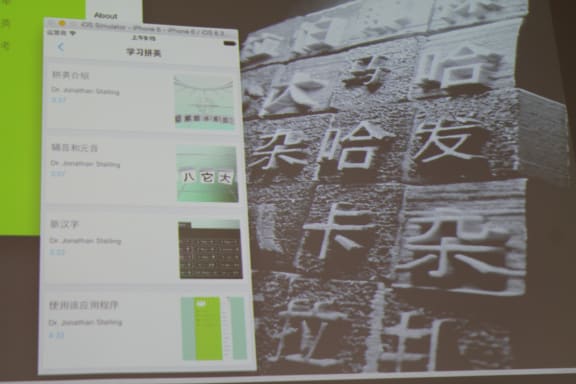

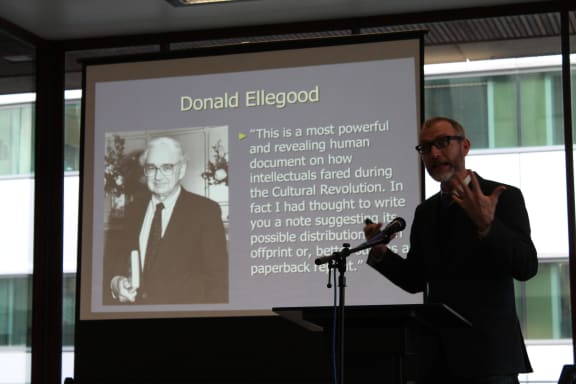

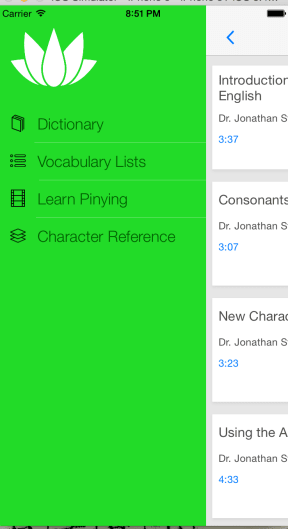

Invited by the Confucius Institute at Victoria University to share his unique knowledge, Dr. Stalling gave public talks at the New Zealand Centre for Literary Translation and the National Library about his creation; a new alphabet and new way of learning to write and speak English through the phonetics of Chinese characters - a project he calls ''Sinophonic English''.

Dr. Stalling is the founding Editor of Chinese Literature Today magazine responsible for publishing Sandalwood Death by Nobel Prize winning Chinese writer Mo Yan among other literary luminaries.

Dr Stalling is also the author of the new Tinfish Press publication Lost Wax: Translation through the void which explores the complexity of translation between Chinese and English through his poetry.

In Lost Wax, Stalling presents a sequence of poems about his wife's work as a figurative sculptor as she moves her pieces through the bronze casting method (from clay, to wax, to bronze). In Lost Wax, Dr. Stalling's poetry becomes the "parallel literary art work" through the process of it's translation and re-translation.

Dr. Stalling became the first western Poet-in-Residence at China's prestigious Beijing University in 2015 and routinely travels the globe to discuss his innovative approaches to bridging Chinese and English through poetry, translation and pilot digital platforms, these projects can be viewed on his TEDx Talk.

"There are more speakers of Sino-English than there are Americans alive!" Dr. Stalling tells me.

I'm with him on the wind swept sixth floor of the NZCLT at Victoria University sampling excerpts from his funky Sinophonic English Opera Yingelishi and witnessing his remarkable live performances. His concepts are dynamic, its brain expanding stuff.

Sino-English: a new global language Photo: Photo courtesy Professor Jonathan Stalling

"I believe we will be able to move beyond and between our languages more freely, intuitively and effectively as soon as we start using different writing systems to bridge languages rather than imagining them as walls between them.''

Jonathan Stalling was 12 when he first learned to speak Mandarin. His parents would drive him 50 miles from his hometown in Arkansas to take lessons at the home of his Chinese tutor. Through all of high school until he learned to drive himself. Now that's dedication.

Why the drive to learn Chinese? Were there any other students?

"No, I was it. I grew up in a small arts community in Arkansas back in the 1970's called Eureka Springs. It's very beautiful." Arkansas, the southeastern U.S. state bordering the Mississippi River is known for its resplendent parkland, mountains, rivers, hot springs and caves.

"My step-father taught Chinese martial arts, so I grew up in a family of Qi Gong and Tai Chi practitioners and other martial arts. My father is an abstract expressionist Buddhist and my mother is where I get my English side, she's very Victorian and an artist with a deep love of poetry and literature," he tells me.

"In between this is the inter-language space, the inter-cultural space of my Bohemian upbringing under the roof of counter-culture artists in Arkansas. By the time I was old enough and had some agency - Chinese was where I made my life choice. I learned to memorize classical Chinese poetry through my high school years."

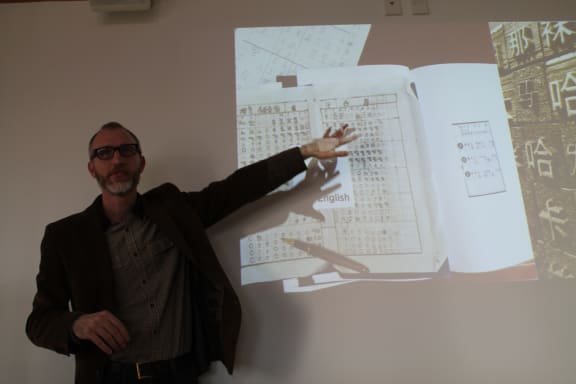

Sino-English Photo: Photo courtesy Professor Jonathan Stalling

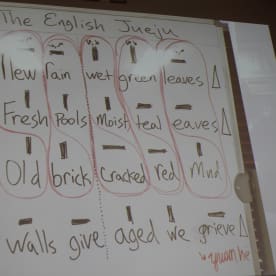

Your new alphabet Sino-phonic English where did it all start?

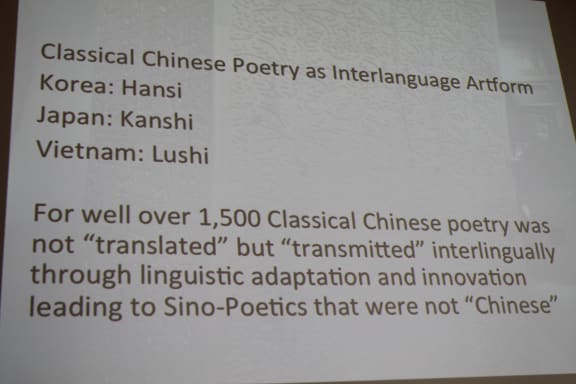

"It started in inter-language itself, between English and Chinese. These two global languages have a long history, almost 200 years old in terms of print. The first printing was in the 1840's of phrase books that would teach English using Chinese characters." he explains.

"Almost all Chinese users will use Chinese characters to memorise English and that has had a lasting imprint on the form of English that's been created during that time. It's now one of the dominant forms of English on the globe. There are 350 million speakers of China-English - a fusion of the two global languages."

Is this where the term "Chinglish" comes from?

"The word "Chinglish" is a loaded term. We think of the term in the context of the late 19th Century with the Chinese diaspora moving out [around the globe]. They met with resistance, part of that resistance would be turned into cultural productions that would try to dehumanise the Chinese diaspora."

Dr. Stalling tells me that the very first phrase book published in Canton in 1843 was titled; Language of the Red Haired Barbarians.

The title is an eloquent reminder of how the Chinese must have viewed the British, particularly in the lead up to the two Opium Wars in the mid-19th century involving Anglo-Chinese disputes over British trade in China and China's sovereignty. The wars and events between them weakened the Qing dynasty and reduced China's separation from the rest of the world.

Dr Luo Hui introduces Professor Stalling at Victoria University Photo: RNZ / Lynda Chanwai-Earle

"I prefer to use the term "Sino-phonic English" a word of my own creation to talk about what this really is; an "English" with saturated Chinese phonemes (one of the units of sound that distinguish one word from another in a particular language) which have been redistributed into diction and grammar. This has matured into various dialects."

It's worthy to note how this hybrid inter-language is now a dominant form of English spoken worldwide.

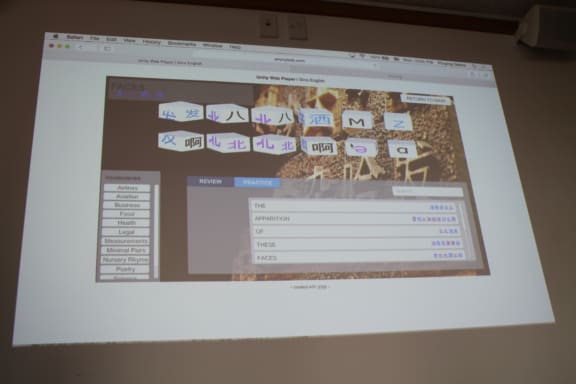

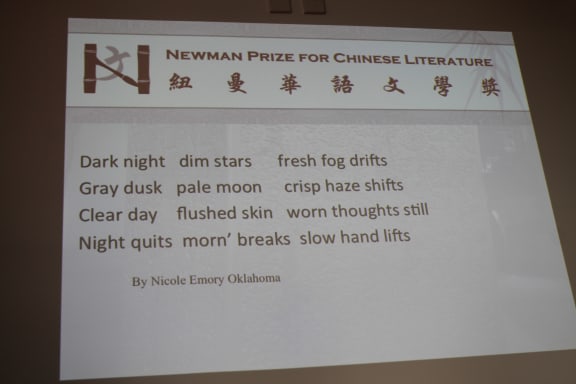

"My opera "Yingelishi" works with the history of the term "Chinglish". I took these phrase books and rewrote one into a libretto which became the opera Yingelishi he tells me. " I wanted to challenge the history of the reception of the sound structure in the Western imagination. Rather than hearing this as a form of ridicule I wanted to re-situate the whole thing, make it poetic in the form of an opera."

Sino-English: a new global language Photo: Photo courtesy Professor Jonathan Stalling

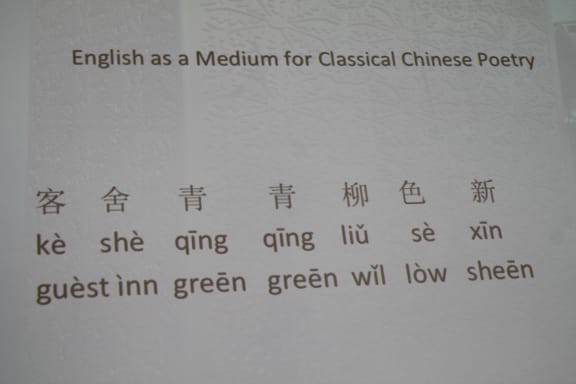

Simply put, how does it work?

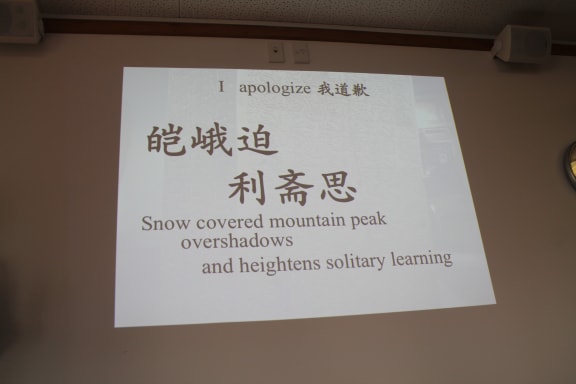

In Dr. Stalling's opera a woman sings in English – “Oh my god! Oh my god! Oh! Robbery! Thief! Thief! My passport! All my belongings!” – But the literal Chinese translation of the word "robbery" or "ro-ber-ee" means "beautiful waves, wisdom."

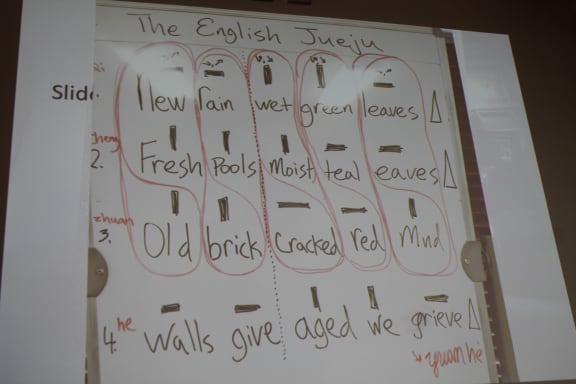

"English" is pronounced by a Chinese speaker as "Yingelishi" or "Yin-ge-li-shi". This word becomes the new inter-language. When "English" is translated into Chinese characters the word becomes a poem "Chanted, songs, beautiful, poetry ..."

"So how can we make the word "English" with Chinese characters without that disruptive nature? The word "yin-ge-li-shi"has sounds that pop up between consonants called "echo vowels" [that disrupt the speaking and learning]."

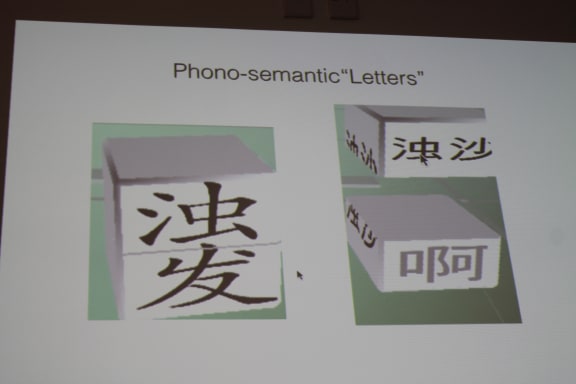

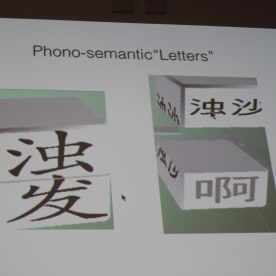

"So what I did is I invented a way of using Chinese characters, that cut the character into consonants and vowels and redistribute them evenly to make the English language phonetically and accurately as letters. That will allow the Chinese user to see the character, understand the sound in the correct order and to pronounce the English word more accurately. This is the new inter-language that one can learn more intuitively and quickly."

My goal is not to "fix" but to deepen our understanding of inter-language. I want to recreate at the DNA level of the phoneme of the sound of these languages and fold them together to make a new form. We think of writing systems as walls between languages, but really they're bridges.