"You could have had a sibling too," startled the 11 year old looked at me long and hard. "You had an abortion too?" - excerpt from "Mothersonhood" by Professor Dai Fan, Sun Yat-sen University.

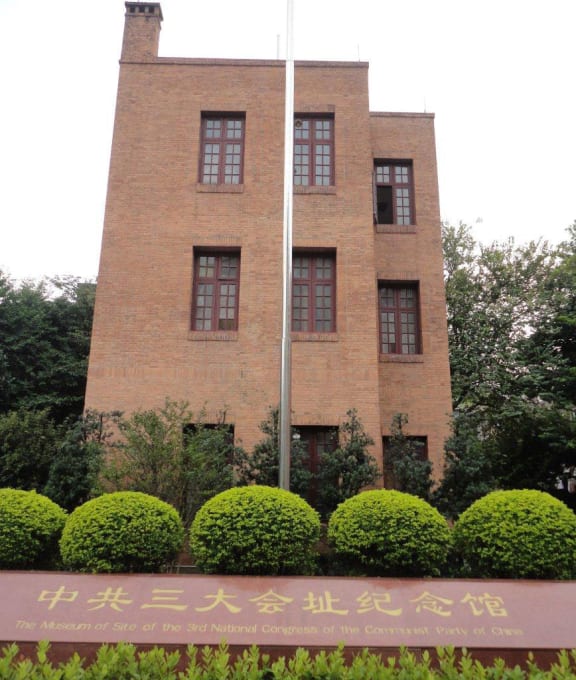

On a recent trip to participate in an international writer’s residency at Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Southern China, I heard the Head of Creative Writing Professor Dai Fan reading from her non-fiction story titled Mothersonhood about a difficult conversation she had with her only child.

She was explaining how she had no choice but to abort the sibling he would never know – her personal take on the enforced one child policy in China.

The one child policy

The one child policy was part of the "family planning policy" to help control the burgeoning population of China and the demand on water and other resources. It was controversially introduced between 1978 and 1980 and was formally phased out in late 2015.

Ethnic minority communities among other exceptions were exempt. 36% of China's population was subject to a strict one-child restriction in 2007 and 53% were allowed to have a second child if the first child was a girl.

The policy was enforced in rural areas through fines based on the income of the family. "Population and Family Planning Commissions" existed at every level of government.

The Chinese government claims that around 400 million births were prevented. A survey in 2008 reported that 76% of the Chinese population supported the policy, however the one child policy was particularly controversial outside of China because of concerns over human rights abuses and perceived negative social repercussions.

The residency saw 12 writers from around the globe meeting at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, the birthplace of my own mother, so it was a return to kin for me in some ways.

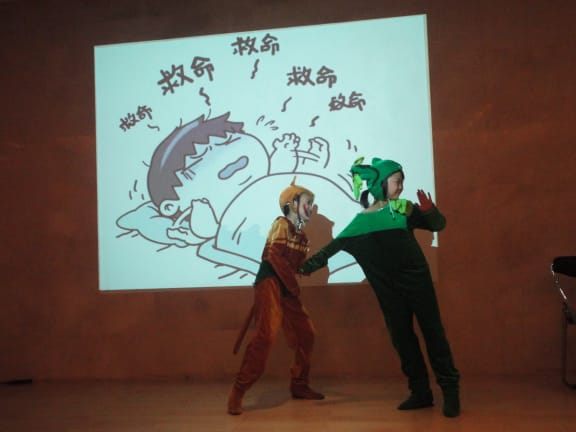

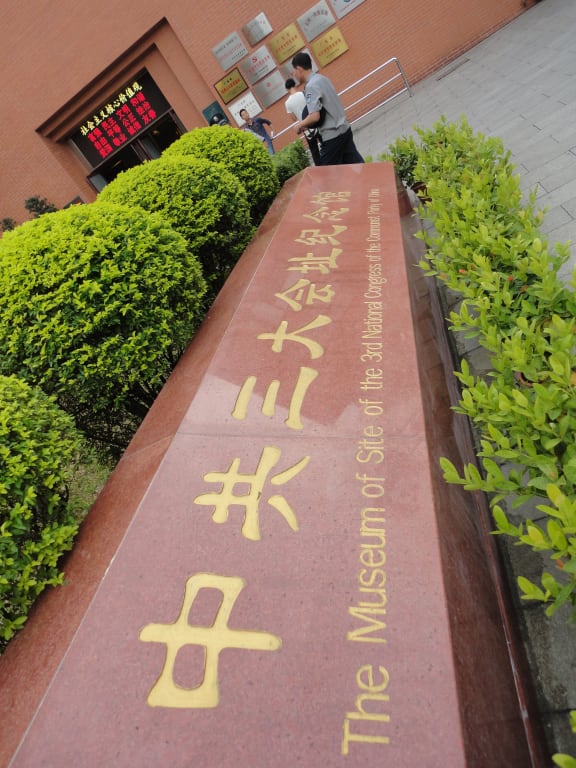

Changing demographics, China's two child policy Photo: RNZ / Lynda Chanwai-Earle

The auditorium hummed with students, writers and academics at Sun Yat-sen University but the crowd fell into a hush as Fan read from her creative non-fiction short story collection. One story was about growing up in China during the 1960's with a social naivety around sexuality, another story reflected the cruelties of the Cultural Revolution but the story that really gripped was Mothersonhood.

Later, while the group were based in Gudou, I asked Professor Dai to tell me more about her life growing up as a child on the university campus and the story behind Mothersonhood.

The silence between us prolonged. "Are you crying?" "No." Yet tears streamed down faster than he could wipe them.

"My name is Dai Fan, Dai is my last name. I was actually born on the campus of Sun yat-sen University - the university has been my world but it made me feel trapped. I felt that my world was far too small. I used to think that everyone grew up on a campus! This inspired my numerous trips abroad after 1994, just to see the world."

"My parents taught Russian and English. I grew up there, I got three of my 5 degrees there. My MFA in Creative Writing is the best degree I have. It started me on a new career path - I started writing and organising things like this residency.

Tell me more about your piece Mothersonhood where you revealed you'd had an abortion to your only child, your son?

"Every time I read it I seem to understand a bit more about what it really means to me.I don't really know about the benefits [of the one child policy]. People would like to have the choice. Even now people would like to have the choice and many lives are lost - and that's painful."

And your son, he's 26, almost 27 now? Is he looking at children himself?

"We never talked about it again. He talks about having children but not in the near future."

The two child policy

On 29 October 2015, the Chinese government announced the new two child policy which became effective from 1 January, 2016.

Although most couples will be restricted to two children, issues remain. After decades of the one-child policy, with a national birth rate well below replacement level of 2.1.

China's new challenge; how to provide for an older population while also encouraging younger residents to have more children.

I asked Fan what her thoughts were on the changes to a two child policy:

"If I had the choice I would have had two children. In theory I think it's a nice thing. The Chinese character of "good" consists of two radicals; one is daughter, one is son, so "daughter" and "son" together is good."

That's what makes a lot of people think that one daughter and one son together would make an ideal family.