On International Women's Day, Otago University history professor Barbara Brookes has provided a snapshot of women's lives in colonial New Zealand.

Professor Brookes' new book, A History of New Zealand Women, asks what a history of New Zealand would look like if the country's development was looked at through the eyes of women.

Photo: Bridget Williams Books

She provides a narrative that "starts from a viewpoint of wives and daughters, and grandmothers and sisters ... from those who considered their lives as distinct from history's 'great men'".

The following passage from her book gives a glimpse into the lives of both Māori and immigrant women, and their day-to-day lives before the suffrage movement was in full swing.

Working for independence

From the start of European colonisation, Māori women were quick to supply newcomers with items for trade, from flax fibre to potatoes, fish and fruit.

Flax was highly valued by Māori, who used nearly all parts of the plant in some way - especially the fibre, which was used for clothing and many other items.

Europeans sought the flax for rope, and admired the skill of the women who scraped the leaves with shells to produce the fibre, producing half a hundredweight a week.

The Sydney traders were said in 1843 to be ''dependent on native women and their shells for the cargoes they obtain''.

Māori families drove pigs down from the Manawatū to Wellington to supply the settlers with fresh pork, and in return purchased blankets, tobacco and "other necessaries".

Women hawked firewood, potatoes, maize and wheat, carrying heavy loads of 50 to 60 pounds in flax kits.

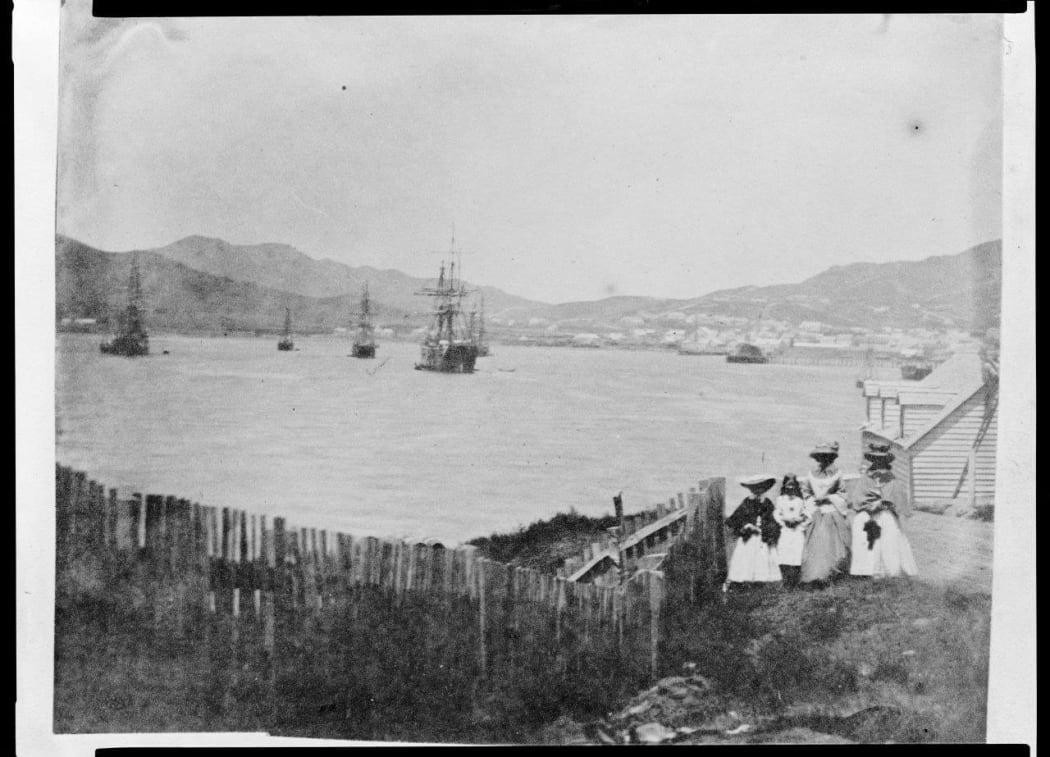

Looking South along Mulgrave Street towards the site of Wellington Railway Station, with a group of unidentified women and girls in the foreground. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library, PA1-f-019-15-5

Immigrant women also took to trade, sometimes supplying Māori women with new goods. Susan Waters set up a store soon after her arrival with her family in 1842 and wrote to her sister, "e sell whatever we can buy, anything or everything; and are getting a tolerable business."

She was quickly engaged in dressmaking, "mostly for native women".

Dressmakers were in high demand; indeed, sewing was second, in terms of women's employment, only to domestic service.

Writing to her sister in 1853, Louisa Rose remarked how she had to wait patiently in Christchurch for an overburdened seamstress to complete work.

She suggested that a Mrs Lewis might consider emigrating: "f she is a good dressmaker even merely good plain workwoman she would get plenty of employment here ... Workwomen are as much wanted here as labourers."

Just as men set up small businesses, so too did women, as historian Catherine Bishop has described.

By careful analysis of the records, Bishop has shown how businesses often operating (for legal reasons) under a man's name were in fact run by women.

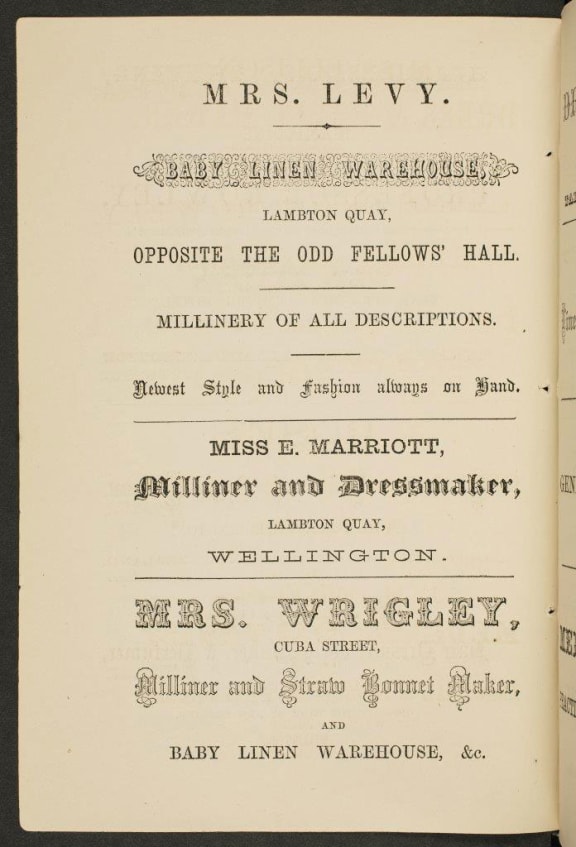

Sarah Masters, for example, ran part of Masters and Perry drapers in Wellington in the 1850s. Another Wellington resident, Jane Levy, married to Solomon Levy, ran a babies' linen warehouse on Lambton Quay in 1866.

Millinery, toy and grocery shops were run by women whether married, widowed or single.

Bull's Wellington almanac and mercantile directory, for the year 1866 - including ads for Mrs Levy's linen warehouse. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library

The opportunity New Zealand offered for independence greatly appealed to Mary Taylor, an educated middle-class woman who felt stifled by English expectations of female domesticity and the rigidity of class.

She noted:

"There are no means for a woman to live in England but by teaching, sewing or washing. The last is the best, the best paid the least unhealthy and the most free. But it is not well enough paid to live by. Moreover it is impossible for any one not born to this position to take it up afterwards."

On joining her brother in New Zealand in 1845, Mary found the freedom she was looking for. She taught, bought land, built a house and dealt in cattle.

When her cousin Ellen Taylor joined her in 1849, they made plans to open a women's clothing and drapery shop.

In 1857, Mary wrote to her friend Ellen Nussey, detailing how the work satisfied her: "t is just the difference between everything being a burden and everything being more or less a pleasure."

She attributed her former "depression of spirits" to the fact that previously her judgement "was always at war with my will.

"There was always plenty to do but never anything that I really felt was worth the labour of doing. My life now is not overburdened with work, and what I do has interest and attraction in it."

Working amicably with her cousin, alternating duties in the shop with housework, Mary operated a thriving business.

Grace Hirst and her daughters also began trading soon after their arrival in Taranaki in the 1850s. Grace's well-off Yorkshire relatives supplied the goods - 'cloth, blankets, shoes, paper, household appliances' - that helped the family establish themselves in that decade and the next.

In Canterbury, products of all types, from "a flitch of bacon to a pair of boots", were on display in "a wonderful storehouse of miscellaneous goods" visited by Sarah Amelia Courage in the 1860s.

Here she acquired numerous small appliances, from a telescopic toasting fork to a nutmeg grater, to ensure she became "a model housekeeper".

A party of men riding around the East Cape in 1866 found themselves short on feed for their horses.

An elderly local woman offered to provide them with seven cobs for one shilling, saying that was all she had. After receiving payment, she found some more and charged another shilling.

"By carefully dividing her attentions amongst us, she artfully contrived to raise 5s or 6s out of as much grain as would barely have sufficed for one legitimate feed for the smallest horse belonging to the party."

Mrs Jane Cross, known for her "shrewd and sound common sense", ran a shop in Parnell, Auckland, in the 1870s.

There she sold, among other things, butter supplied to her weekly by a Mrs Truss. An "esteemed and steady business woman", she also weighed the oxalic acid needed by a milliner, Mrs Gilbert, for the straw plaiting used in her hats.

This network of women's business activities - making and selling the butter required by households, making the hats and weighing the chemicals required for their construction - was common in growing towns where confectionery-makers, drapers and dressmakers catered to the needs of their clients.

At Mrs Walker's Drapery Establishment on Lambton Quay, Wellington, for example, customers could get "eathers cleaned, dyed, curled, and dressed in the French style in all the fashionable shades (including black)".

In shops, public houses, hotels, boarding houses, in their own homes and in the homes of others, women worked for independence, to supplement the family economy, and to support themselves when deserted or widowed.

While wages for female domestic servants stagnated in rural England, the scarcity of help in New Zealand allowed women to set better terms.

The Christchurch labour market report for June 1864 noted the demand for barmaids, who received £2 to £3 per week (comparable to surveyors' men); dressmakers were said to earn £35 to £40 per annum, more than the £25 to £30 per annum a female domestic servant could hope to earn (and less than half the income of a male domestic servant).

"Nurse girls" might hope to earn £20 to £25 per annum, while working girls between the ages of twelve and fifteen could expect to earn £12 10s to £15 per annum - about £1 to £2 less per annum than farm boys of the same age.

But active as they were in the paid labour market, women also carried the burden of unpaid domestic labour in their homes.

A History of New Zealand Woman is published by Bridget Williams Books.