The stiff poses of Victorian folk etched in glass and stored in a Nelson archive have slowly made their way into the digital era.

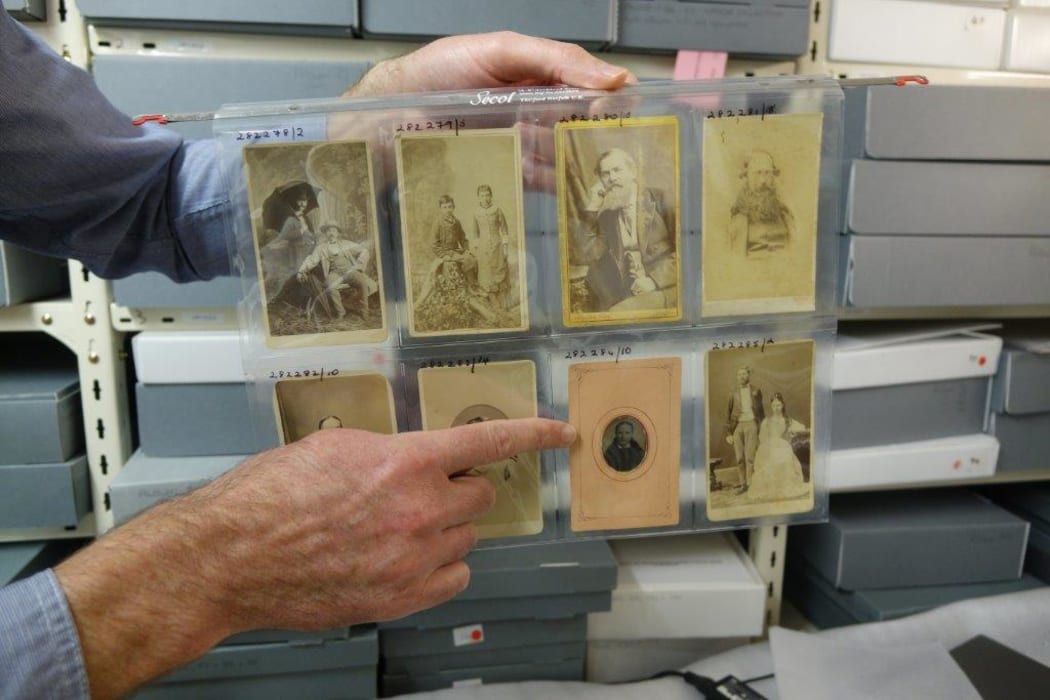

In early times people left calling cards like this. Photo: RNZ / Tracy Neal

The images are part of a long-running project to preserve a rare photographic collection held by the Nelson Provincial Museum, which has been given a last-minute financial boost to help it over the finish line.

Work started seven years ago to scan and digitally archive almost 160,000 glass negative plates, and move the originals from mobile shelving to safer storage.

The project, which has cost around $200,000 so far, stalled last year when the money ran out, but Nelson's civic trust and a private trust, the Bett Collection Trust, recently came forward with a top-up.

The images captured on fragile glass plate negatives, some more than 150 years old, are described by the museum's boss as some of the world's most important.

Darryl Gallagher and Lucinda Blackley-Jimson. Photo: RNZ / Tracy Neal

Chief executive Lucinda Blackley-Jimson said the collection was the jewel in the museum's crown.

"The early images are extraordinary because they show just how much has changed in Nelson, Tasman and Golden Bay. And they're (the images) wonderful because they have that real charm of putting you into a life gone by.

"Then there are also surprising images on glass plates from World War II that we wouldn't have expected," Ms Blackley-Jimson said.

Collection manager Darryl Gallagher said the collection was significant because it was a complete snapshot of a developing region from the 19th century to the 1940s, including at a time when many photographers were wiping plates clean of images in order to re-use them.

It also holds the works of early New Zealand photographers William and Fred Tyree, whose collection formed the backbone of the entire archive, Mr Gallagher said.

The president of the Nelson Historical Society, journalist and author Karen Stade credits a woman named Rose Frank for her part in ensuring the collection survived. Miss Frank became the collection's guardian at the beginning of World War I and later gifted it to the historical society, which in turn gifted it to the museum.

Ms Stade regularly uses the resource and said it was important not only because it was a globally accessible, but it offers a rare glimpse into an English colony.

"It's got significant historical legacy, not only for Nelson and New Zealand but also internationally. New Zealand was the first English colony that has been recorded by photography from its very early days," she said.

Ms Stade said the society was thrilled the project would now be completed this year.

"Because then it will be easily accessible by anyone, anywhere around the world."

Mr Gallagher said the process of converting the images from a negative to a positive digital file was not straightforward.

"Our glass plate processing team photograph the negative and catalogue the information about it. The image itself will get converted from a raw image into a positive one, by an imaging technician."

Snapping an image back then was a much more complicated process than today's point-and-shoot, and required considerable patience from the subject, Mr Gallagher said.

"Sometimes you can actually see braces behind people, to keep them still. People often criticised the Victorian era for the rigidity and the fact the people weren't smiling, but you try standing there for 30 seconds to a minute while holding a natural-looking smile - it's not easy."

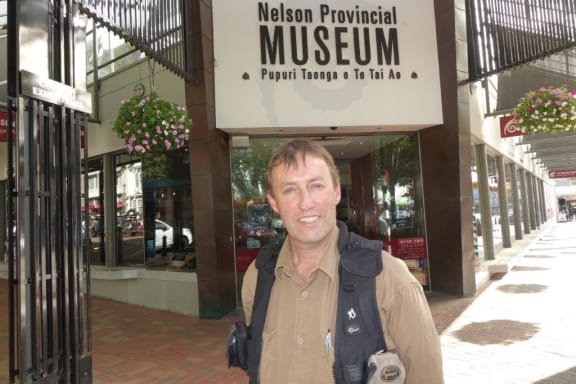

Martin de Ruyter Photo: RNZ / Tracy Neal

The collection also catalogues news events covered by the Nelson Mail, before it went digital in 2000.

The idea to donate almost 30 years' worth of news photographs in negatives was that of then editor, David Mitchell and the paper's chief photographer Martin de Ruyter, who said it was unlikely there would ever be another record quite the same, because photography today was like "candyfloss".

"You know you've consumed something because you've got the wrapping but there's no substance to it - it's there and gone, whereas the images the museum has are there for a period and illustrate development of a community."