Subscribe free to Black Sheep. On iPhones: iTunes, RadioPublic or Spotify. On Android phones: RadioPublic or Stitcher.

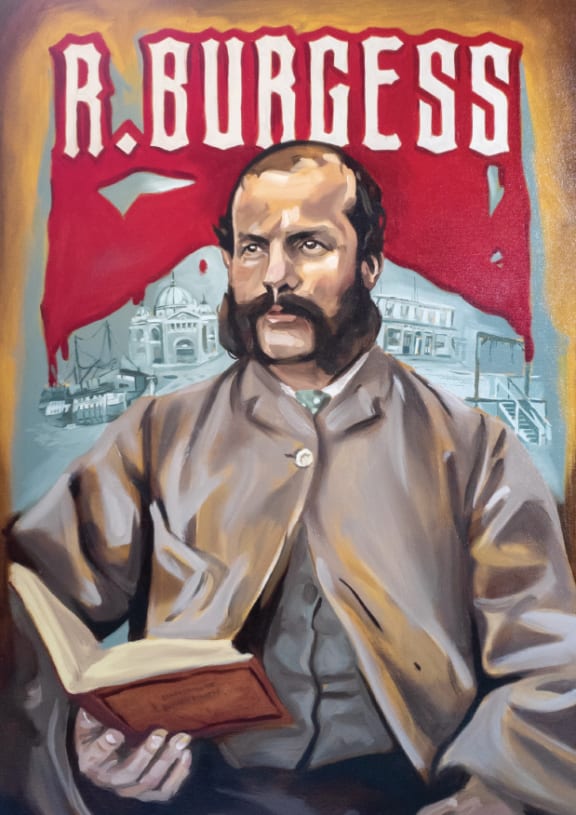

Richard Burgess poster by Massey University student Kane Wills Photo: Kane Wills

Richard Burgess may be the most prolific murderer New Zealand has ever seen.

It’s estimated the death toll his gang of outlaws inflicted while roving the goldfields of the South Island in the 1860s ranged anywhere up to 35 people.

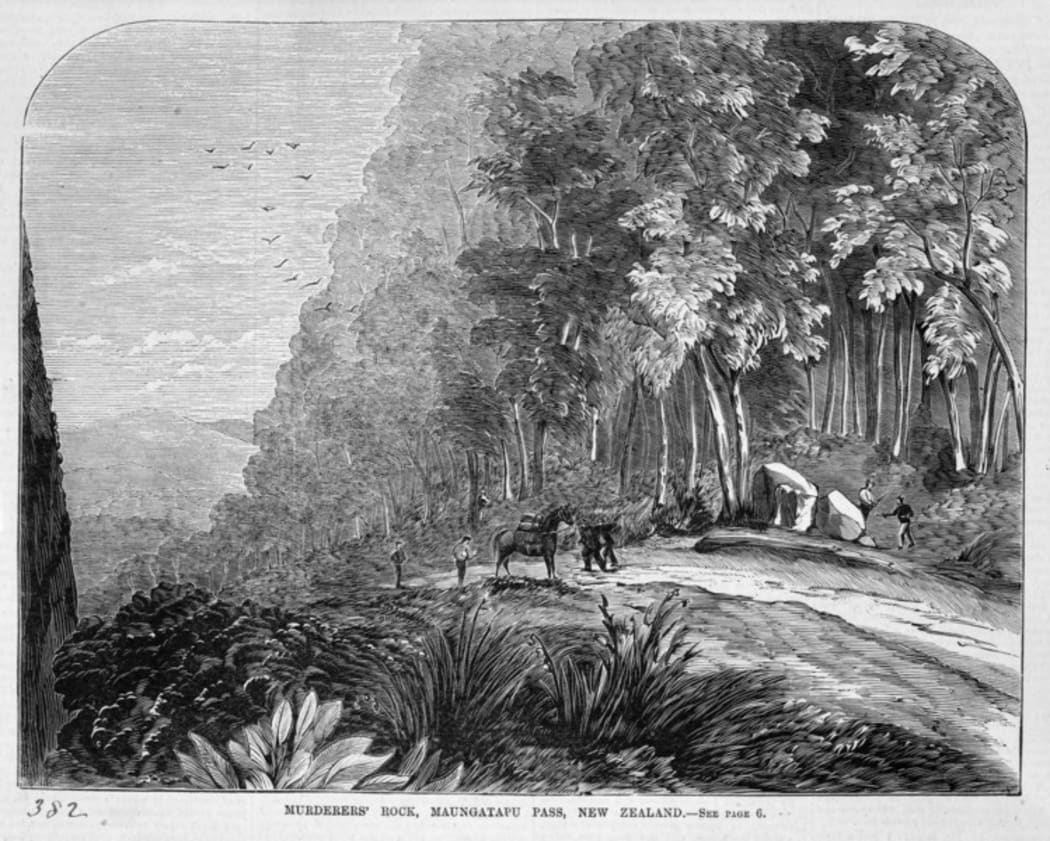

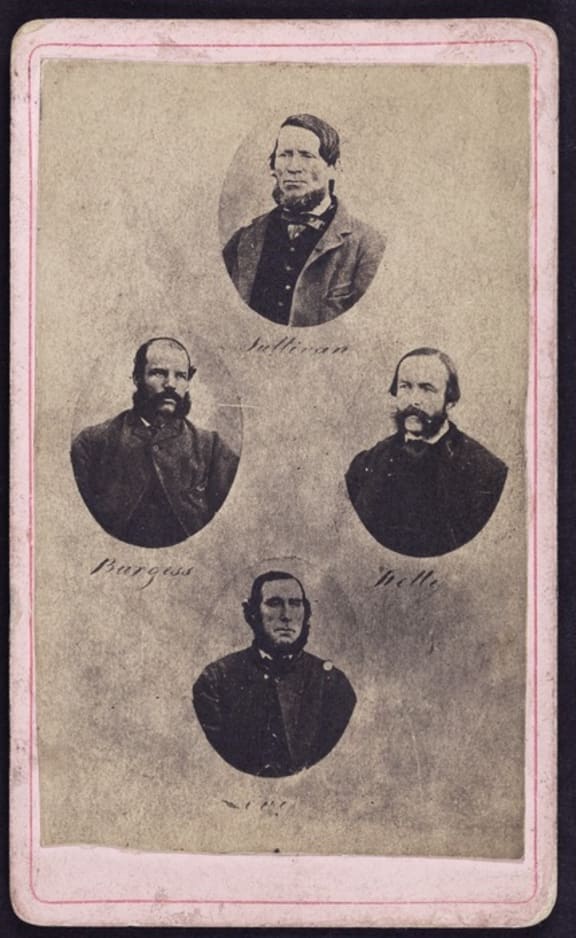

The Burgess gang are best known for the so-called Maungatapu murders, crimes which saw all but one of the gang hanged. The lone survivor was Joseph Sullivan, who turned traitor to save his own skin.

Burgess' story has inspired several books and magazine features. Currently, a play about his gang’s exploits is touring the Marlborough Region.

He sealed his place in New Zealand history with a 46-page confession described as “without peer in the literature of murder” by the famous American author Mark Twain.

“It certainly does make for amazing reading,” says Wayne Martin, author of Murder on the Maungatapu. “Right the way through he’s quoting anecdotes from classic texts and scripture.”

Burgess had a love of literature instilled by his mother while growing up in London’s Hatton Garden in the 1840s. But although she passed this interest on to her son, she wasn’t able to curb his violent, criminal streak .

“He followed your classic Victorian street criminal way of life,” says Wayne Martin. “[He went] from pick-pocketing to crimes of violence [which] eventually caught up with him and saw him transported to Australia.”

Martin describes Burgess as “hopelessly addicted to crime”. And with more than 80 percent of the police force having resigned to seek their fortune in the gold rush in the 1850s, Australia wasn’t the best place to kick a criminal addiction.

An 1866 Australian wood engraving of the holdup scene. Photo: Ebenezer and David Syme, August 27, 1866, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, Accession No. IAN27/08/66/8

From his late teens and into his twenties Burgess roved the goldfields of Melbourne as part of a gang, robbing miners. Eventually those crimes caught up with him and he was introduced to the horrifically brutal colonial justice system - in particular, the floating prison hulks anchored off the coast of Melbourne where he spent eight years of his sentence.

Wayne Martin believes the brutality of those prison ships is what turned Burgess from a relatively normal criminal into a monster.

“The prisoners on those hulks swore that if they got out they were not coming back to a place like this. They were not going to leave witnesses to testify against them,” he says. “That was the seed of the monster he became and also this policy of killing not to leave witnesses.”

Burgess was eventually released in 1859 but didn’t remain in Australia for long. He fled for New Zealand with a partner in crime called Thomas Kelly.

“Australia had become too hot for him… He fled to New Zealand.” says Wayne Martin. “The New Zealand goldfields were getting underway so there was that added lure. [Burgess and Kelly] always followed the gold.”

Four separate photographs of the four men involved in the Maungatapu Murder. They are Thomas Joseph Sullivan, Philip Levy, Richard Burgess, and Thomas Kelly. Photo: Ref: PA2-2593. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23151265

The pair initially settled in Dunedin as part of a gang, robbing gold miners throughout the Otago region. But a bungled robbery at a campsite near the Tuapeka River led to a gunfight with the police and Burgess was again locked up.

While in Dunedin Prison he received 36 lashes for his part in a prison riot. After that incident another prisoner claimed that Burgess went down on one knee, clasped his hands together and swore to “take a human life for every lash and indignity” that had been laid upon him.

After being released from prison in 1865 he did his best to try and fulfill that oath.

Burgess and Kelly trekked from Dunedin to Hokitika. They formed a new gang that travelled up and down the West Coast committing robberies and murders.

Exactly how many people the gang killed is unknown. Wayne Martin estimates there were upwards of 20 victims, which he says would make Burgess “New Zealand’s worst serial killer”.

The gang were eventually caught after they travelled up to Nelson where they murdered five men on the Maungatapu track. One member of the gang, Joseph Sullivan, turned traitor in exchange for a free pardon.

At this point Burgess wrote his famous 46-page memoir. It was partly intended to record his life story, with the ulterior motive of implicating the treacherous Sullivan directly in the killings and diverting blame from two other members of the gang, Thomas Kelly and Phillip Levy.

Despite having confessed to the murders, Burgess pleaded not guilty. This gave him the chance to confront Sullivan in court in what Wayne describes as “the highest most riveting drama”.

“These guys are defending themselves, but doing so with great skill,” Wayne says. “You’ve got Sullivan on the stand for 12 or 13 hours undergoing vicious cross examination by Burgess and Kelly; and parrying them off with equal skill.”

In the end the jury found the gang guilty and all but Sullivan were hanged for their crimes.

Listen to the full Black Sheep podcast to hear about Richard Burgess’ final dramatic moments at the gallows, for more detail of the brutal prison hulks and for the chilling details of the Maungatapu Murders.

Listeners of Black Sheep may enjoy Eyewitness, a series which tells the stories of dramatic moments in history through the eyes of those who witnessed them firsthand.