Our fates are tied to the fate of our oceans, which generate half of the world's oxygen, as well as provide water, food, recreation, culture, and some $24 trillion of the global economy. But ocean life is under threat by multiple stressors — climate change, acidification, plastics, pollution, overfishing, overexploitation, and dead zones. What can be done now to avert disaster?

Led by Dr Maria Armoudian, a panel including Professor Simon Thrush, Professor Emeritus Nordin Hasan, Dr Rochelle Constantine and Dr Dan Hikuroa looks at how we can better protect the future of our seas.

How whale poo keeps the ocean live

Humpback whale jumping Photo: Wikimedia Commons

According to marine biologist Dr Rochelle Constantine at the University of Auckland, most of the problems facing the ocean are of mankind’s doing. Working in conservation science – otherwise known, she jokes, as the science of guilt – the attitude of researchers tends to be ‘We broke it, so what are we going to do to fix it?’

That idea of tipping points is very much in her mind as she is currently knee-deep in research in advance of several voyages to Antarctica later this year. She’s focusing on humpback whales which breed in the tropics in the winter and go south in the summer months to Antarctica to feed.

And she cites research which has been done into the effect a century of commercial whaling had not only on whale species, but on whole systems of Antarctic marine life. Over two million large baleen whales had been removed from the Southern Ocean over just a few decades, and by the 1960s the whale stocks of Antarctica had collapsed.

“As you can imagine these animals are immense,” says Dr Constantine. “Up to about 50 tonnes in weight. And all they do when they’re down there is feed, consuming massive amounts of primarily Antarctic krill.” (These are the small marine crustaceans which form the bottom of the Southern Ocean food pyramid.)

So, when whales mostly disappeared, ecologists at the time expected there to be a massive boom in krill numbers because the main things that were eating them had gone. They anticipated a further boom in penguin and seal populations (also krill eaters) as they were then recovering from near-extinction.

But why that didn’t really happen has only recently been discovered.

Dr Maria Armoudian, Professor Simon Thrush, Dr Rochelle Constantine, Professor Emeritus Nordin Hasan, Dr Dan Hikuroa Photo: RNZ / Paul Bushnell

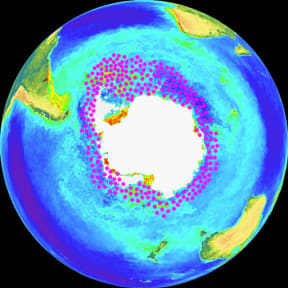

The Southern Ocean is an iron-limited environment, and the micronutrients of iron are needed for life to occur. So the key question was ‘Where’s this iron getting locked up?’ Recent research has revealed that this occurs at the krill stage of the oceanic life cycles. And it was found that whales played a crucial role in freeing up this iron, which was otherwise bound up in the physical structure of the crustaceans.

Where krill are found – concentrated round the Antarctic Peninsula Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“When whales eat krill,” Dr Constantine says, “and poop what remains out their back end, that iron concentration in the whales’ poop is ten million times that of normal background levels.” The whales act, effectively, as iron seeders – taking the iron which was locked up in the system, filtering it through their bodies and releasing it back into the waters of the Southern Ocean to support new life.

Having made this discovery, researchers hypothesised that this was the thing that stimulated the phytoplankton production in the summer months. Whales were needed to make the system productive. When their numbers collapsed due to whaling, the results to the ecosystem were catastrophic.

“I have no doubts,” she concludes, “that we did something really terrible when we removed so much mass that it actually really changed how the Antarctic system functioned.” The sad news is that despite the gradual recovery of whale numbers due to increased protection, it’s unsure whether the full iron-seeding ecosystem can be restored due to other man-made stresses, such as climate change, which is altering the presence of sea ice.

Esperanza Base in Antarctica Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Participants: Dr Maria Armoudian, Professor Simon Thrush, director of the Marine Science Institute, University of Auckland; Dr Rochelle Constantine, marine biologist, University of Auckland; Professor Emeritus Nordin Hasan, founding director of the Institute for Environment and Development and former leader of the International Council for Science for the ASIA Pacific region and advisor to Future Earth; Dr Dan Hikuroa (Ngāti Maniapoto, Te Arawa, Waikato-Tainui), Research Director for Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, University of Auckland.

Links for further reading:

Bottoms up: how whale poop helps feed the ocean

Mātauranga Māori—the ūkaipō of knowledge in New Zealand

Photo: University of Auckland

This session was devised by the University of Auckland's Project for Public Interest Media in association with RNZ.