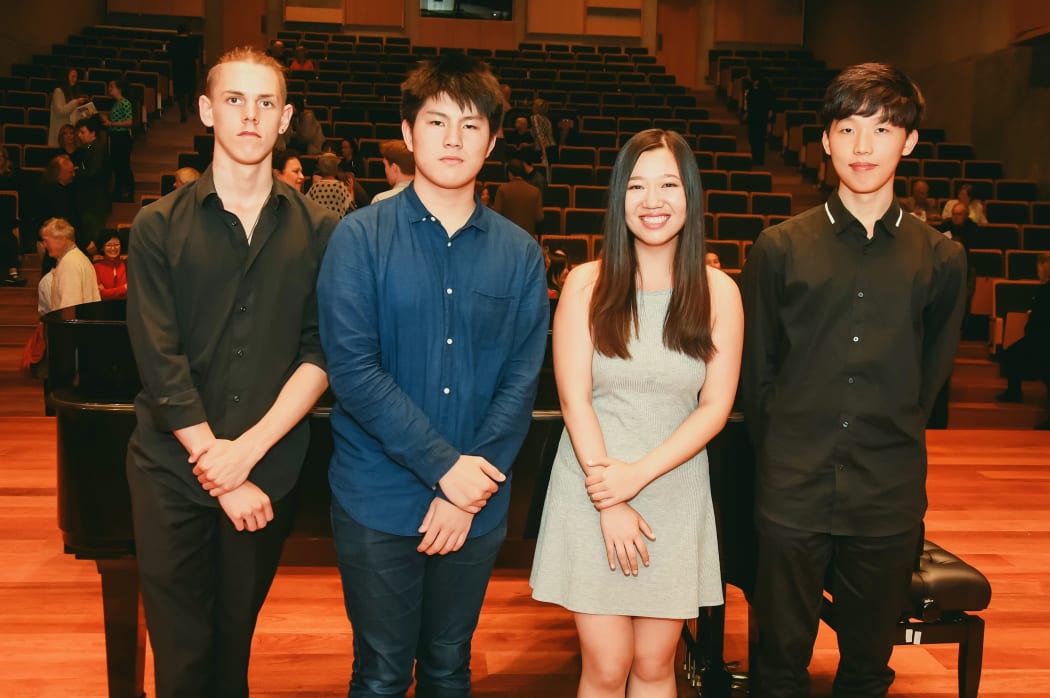

National Concerto Competition performers: Matthias Balzat, Delvan Lin, Siyu Sun & Hye In Kim Photo: Supplied

Auckland cellist Matthias Balzat was the Grand Prize winner of the National Concert Competition on Saturday with his performance of Shostakovich’s first Cello Concerto. Tony Ryan was there and explains how the result of the piano prize was divisive and assesses whether Balzat was the stand out performer. We’ll also hear from winner Matthias Balzat about what it means to with the competition

Matthias Balzat Grand winner of the National Concerto Competition Photo: David McCaw

Tony Ryan reviews National Concerto Competition 2017 – NZSO Conducted by Hamish McKeitch

I love concerto competitions. They are a recipe for intense and convincing performances with that extra competitive edge. But this one was even more special with four towering masterpieces in a single concert. It was an unforgettable night as every performance sizzled with excitement and commitment, but I couldn’t help thinking that these four 17, 18 and 19-year-olds had no business being able to project the expressive depths of this great music with such technical mastery and communicative flair.

Did I agree with the adjudicators decisions? Well, in a concerto competition, I’m sure that every member of the audience chooses their own winner before the official decision is announced, and if that we don’t agree, we tend to think the judges are wrong. But when the performances are all so consistently masterful as the four that we heard on Saturday, I’m sure that every permutation of the order of placings could be found among the members of the audience. However, a few minutes into one performance I leant over to my wife and whispered “this is the winner!” Well I turned out to be right, but I also think that there will have been few people, if any, in the auditorium who would have disagreed. But let’s talk about the performances in their order in the programme.

Hye In Kim – Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor Op. 104 (1894-1895)

The night began with Dvořák’s wonderful Cello Concerto played by Kim Hye In. And while it may not have been quite in the same class as the winning performance, it was a youthful and committed performance that drew attention to every facet of the work’s infinite variety of invention and inspiration. With a famous international soloist, we tend to take lots of things for granted and forget that the skill and artistry that has gone into the preparation will have involved many hours of blood sweat and tears. Somehow, in Kim Hye In’s performance, we saw all the thought and creative imagination that had gone into it, and perhaps that’s what prevented it achieving that last ingredient of a winning formula. I found myself analysing every element of the performance from tempo changes to the sound of the cello in its different registers, the soloist’s integration with the orchestral texture, the acoustic of the venue and so on. During the orchestral introduction, the dramatic change in tempo and dynamics for the second theme seemed extreme, but when the soloist later treated it the same way, I presumed it was his decision and not the conductor’s.

The dry acoustic of the venue also affected that same section of the orchestral introduction, where I couldn’t hear the crescendos and other subtle dynamic variations that the composer took such pains to write. And then, the cello itself had a rather nasal tone-quality in its middle register and I wondered if that was the instrument, the acoustic or the player. There were also a couple of places where soloist and orchestra were not totally together, and I wasn’t sure whether to blame the soloist or the conductor for this. But I don’t mean to sound negative, because I enjoyed and admired Kim’s performance hugely. But I mention it because none of these thoughts even occurred to me in the other cellist’s performance.

Delvan Lin – Rachmaninov: Rhapsody of a Theme of Paganini Op. 43 (1934)

Next came the two pianists, one each on either side of the interval. Both played Rachmaninov and both gave superb interpretations. But if the audience were divided regarding any of the adjudicators’ final decisions, it would be about the relative placings of the pianists. It was a close call and it’s hard to know how the judges were able to separate them.

First up was Delvan Lin with the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini which is one of Rachmaninov’s last major works and it’s a great piece, well-known because of its famous 18th Variation, an ingenious version of Paganini’s original theme. And when Delvin Lin got to that variation, it was a moment of absolute magic. Delvan Lin played every one of the twenty-four variations with detailed attention to the individual character and imagination of each. And he highlighted the contrasts between each variation, as well as conveying the overall architecture of the piece. Perhaps the judges felt that more integration of the connections from section-to-section was needed, or maybe they felt that the choice of work was not as demanding or “concerto-like” as the Piano Concerto that gave the piano first prize to Siyu Sun.

Siyu Sun – Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 2 Op. 18 (1901)

Siyu Sun played the famous and hugely popular Rachmaninov Second Piano Concerto that dates from 1901, much earlier in the composer’s career. This performance had all the power, virtuosity and cantabile beauty that you could ask for. But, for me it was a more conventional performance than Delvan Lin’s, without the same degree of personality that he brought to the Rhapsody. But what she did have was a sense of the music’s romantic opulence and appeal, and this she delivered in spades, but maybe not with a sense of despair-turning-to-hope-turning-to-triumph it demands. But, once again, it was a performance of genuine maturity and mastery and had me wondering how the judges could separate these two magnificent performances.

If these three had been the finalists in a normal National Concerto Competition, we might have been at a loss to try to guess the adjudicators decisions. All three demonstrated musical maturity well beyond their years; all three gave masterful and engaging performances; all three justified their inclusion in the Final concert; and all three proved that they deserved to play as soloists with the NZSO.

Matthias Balzat – Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No. 1 in Eb major Op. 107 (1959)

But then came seventeen-year-old Matthias Balzat with Shostakovich’s first Cello Concerto, and within a few bars we knew who the winner was. The music was in his body, his fingers and his brain as if it could be no other way. The cello seemed like an extension of his body and, for the first time any cares I had about the acoustic, the instrument, the work, the age of the player, or anything else, totally disappeared. He convinced us that this concerto was as great a masterpiece as anything else on the programme and we forgot that this concert was already over two-and-a-half hours long. It was a performance that I’d have been grateful to have witnessed in any context. If the judges hadn’t awarded him the Grand Prize, he’d still have been the winner for me. The fact that this was a competition simply didn’t matter: it was a masterly and charismatic performance by any standard and I will certainly be going to hear this player again whenever I get a chance. Part of the prize is an opportunity to play with the Christchurch Symphony in their next season, so I look forward to that very much.

It’s always hard to say what makes a performance special, but, thinking back to Saturday night, I’m aware of dynamic contrasts that just seemed natural and right, fierce and energetic attack in virtuoso passages that were probably huge risks for Matthias Balzat, but to us were just part of the rightness of his performance. He gave us that rare feeling that “nothing could go wrong”. And the way he was at-one, with conductor and orchestra, was the same as the way he was at-one with his instrument. The NZSO and Hamish McKeich seemed to match every twist and turn of the soloist’s volatile and seemingly spontaneous and charismatic performance. I’ve heard this concerto in concert several times before, but this was special and I doubt that I’m ever likely to hear it played better, communicating as Balzat did, all the harrowing unease that lies behind so much of Shostkovich’s work.

Then, while we waited for the judges’ decisions, we were reminded of the success of many of the musicians who had previously been finalists in the fifty-year history of the National Concerto Competition. Firstly, we had an original composition from violinist Mark Menzies, the winner in 1986, and who’s just been appointed Professor of Music at Canterbury University. He was accompanied by Tim Emerson on piano, who was placed 2nd in 1987. Then a line-up of eight members of the NZSO came back on stage. They had all been finalists (some winners) in the competition at some stage and each talked briefly about what they’d played and a few other interesting memories. Three of the four adjudicators were also winners or finalists at some stage and all continue to have successful music careers. What a great idea to have them back judging this anniversary competition!

The National Concerto Competition Trust had also commissioned Wallace Woodley to compile a booklet listing all the previous finalists and outlining their subsequent careers. This brought back many memories and delightful surprises for many in the audience. The booklet is available to buy for $5.00 from the trust.

This Concerto Competition Final was a special evening and all four competitors should feel very satisfied with their performances. It’s just a pity that, in a competition, there can be only one winner, and on Saturday, it was Matthias Balzat.