Fifty-four refugees detained by Australia on Nauru and Papua New Guinea's Manus Island have been accepted for resettlement in the United States.

Under the deal struck between Canberra and Washington last year, the US State Department announced it was in the process of notifying the first group of detainees about their pending relocation.

Manus refugees checking the detention noticeboard Photo: supplied

The Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull said about 25 refugees from both Nauru and Manus had been selected.

He said a large number of detainees were still being vetted with Washington having agreed to resettle up to 1250.

Yesterday, detainees on Manus Island were issued with appointment slips summoning them to meetings to be notified about their selection for relocation.

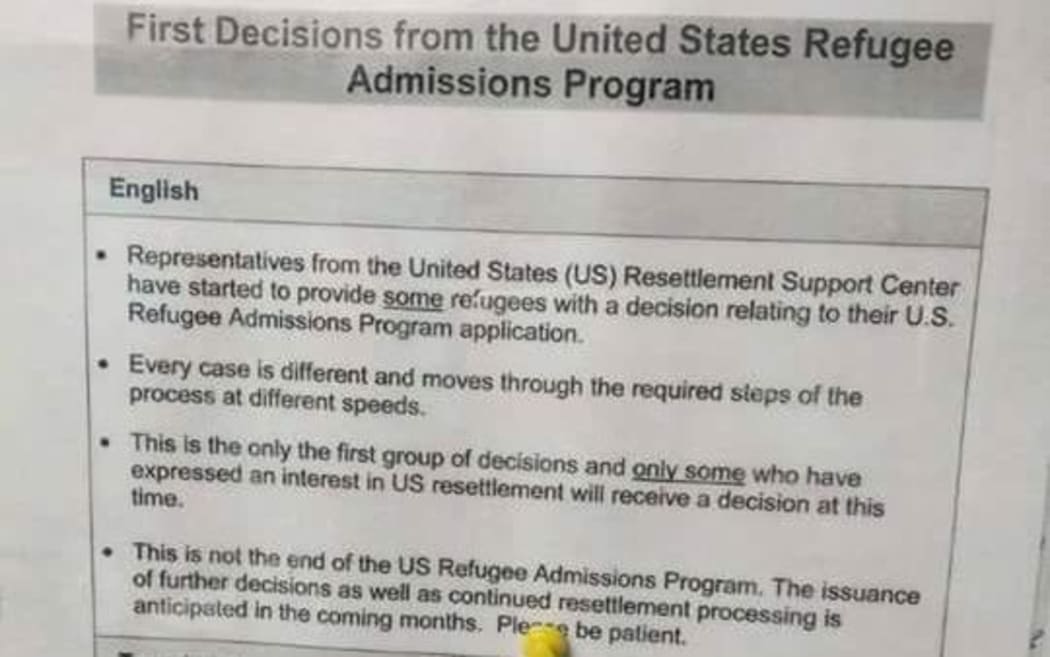

A notice posted in the detention centre assured otheres that today's meetings were not the end of the process and that further resettlement decisions would be made in the coming months.

Refugee advocate Ian Rintoul said three Sudanese refugees on Manus Island had been accepted by the US.

He said they would be flown to Port Moresby this weekend and to the US two days later.

"This is good news for these refugees who have been illegally held on Manus for four years," said Mr Rintoul.

The notice posted in Australia's offshore detention centres about the first intake of refugees for US resettlement. Photo: supplied

Canberra said about 1500 of the refugees it had detained offshore since 2013 were eligible for US resettlement but advocates argued that more than 2000 asylum seekers had been marooned by Australia on Manus Island and Nauru.

The Human Rights law centre calculated that 1783 detainees on Nauru and Manus Island had been assessed as refugees and that of the more than 2000 people "warehoused" offshore by Australia, 169 were children.

About 200 men on Manus had not been granted refugee status, according to the Australian government, with those men facing repatriation, refoulement or further detention in a new prison camp being built in Port Moresby.

Some refugees with family members in Australia had not applied to be moved to the US and the Law Centre's Daniel Webb said for those people the US deal offered "no way forward."

"There are a handful of families ripped apart by offshore detention. Fathers separated from children. Sisters separated from brothers. For them, the US deal won't end their pain. It is not a pathway for their family to finally be together again," he said.

"For them, the way forward is painfully simple - an absolute no-brainer. Permanently ripping apart families is fundamentally wrong. This handful of families must be reunited in Australia - it's a matter of basic decency."

Protest in Mike compound, Manus Island detention centre, 22-8-17 Photo: Supplied

Mr Rintoul agreed US resettlement would not provide a solution for all of Australia's offshore detainees.

"Even if the US deal is met in full, there are not enough places for all those who need protection. The government should immediately halt its moves to forcibly close the Manus detention centre until there is a safe solution for everyone on Manus Island," he said.

"The forced closure and forced transfers are pushing people into unsafe conditions in Port Moresby and East Lorengau, when there are no plans for ensuring they have a secure future."

Canberra moved about 100 detainees from Manus to a Port Moresby motel last month as it continued to coerce about 600 refugees to leave the detention centre for a 400 bed 'transit centre' in nearby Lorengau.

The Kurdish journalist and detainee Behrouz Boochani said letters had been received by some refugees about the centre's looming closure on October 31 and presented them with their options for relocation.

They were instructed to either move to the transit centre, find accommodation in the PNG community, organise voluntary repatriation or resettlement in a third country.

Mr Boochani said drinking water was being restricted and food quality deliberately degraded as part of efforts to force the men out of the detention centre and into the Manus community where refugees were regularly attacked by locals.

He noted refugees were protesting peacefully in the Manus detention centre "every day at 2pm because they don't want to live in PNG."