Between Hawaii and California is a swirling vortex of rubbish twice the size of Texas.

Known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, it's largely plastic waste that has been corralled into one place as ocean currents converge.

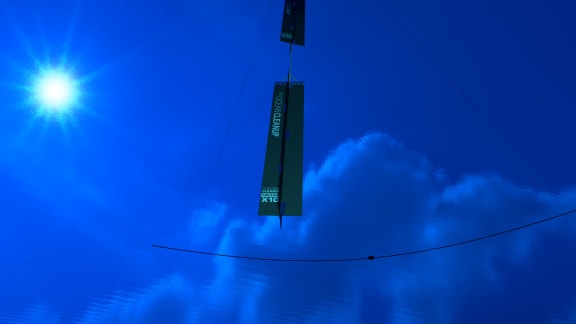

All images in the gallery above are courtesy of theoceancleanup.com

Eventually the contents of the patch - which include nets, crates, buoys, and even combs and toothbrushes - will degrade into micro-plastic fragments that fish will ingest and introduce to the food chain.

It's the kind of large-scale problem you wouldn't expect a Dutch teenager to be taking on, but Boyan Slat decided to do something about it when he was in high school.

The result, seven years on, is The Ocean Cleanup Foundation.

So far, Slat has raised millions of dollars for his plan and just announced new technology to remove half of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch within five years.

He tells Jesse Mulligan that it all started on a diving trip to Greece when he saw more plastic than fish.

"There was this consensus that it would be impossible to clean it up, but at the same time I really didn't see any serious proposals to see whether it could be done."

Physically cleaning the oceans with nets would take "tens of thousands of years and billions of dollars" Slat says.

Instead of chasing the plastic, he had the idea of letting it come to him.

"We've developed a passive system which uses very long floating barriers basically acting as an artificial coastline where there is no coastline, using the natural ocean currents for our advantage."

Slat's TED talk on the project went viral and allowed him to start crowdfunding his clean-up idea.

He says clean-up efforts are best directed at the five areas in the world where converging currents (known as gyres) had led to a congregation of ocean plastic.

"I chose the North Pacific to start as it's by far the largest one - a third of all plastic of all the seas and oceans combined is there.

"It's an area about 2.5 times the size of Texas. Some people imagine it as a floating island of trash, but it's much more dispersed than that. Even though there's a lot of plastic it's also spread out over this vast area."

The good news is most of this trash has yet to degrade.

"Most of the plastic in these patches are still large objects, only three percent has broken down into these small and hazardous microplastics.

"It's not too late to clean up but it also underlies the urgency - these large objects will all become these microplastics over the next few decades if we don't clean it up."

So how does it work?

A very long U-shaped floating barrier which will collect and concentrate the plastic floating in the ocean.

The barrier will be about 1.2km in length, 4 metres deep (deep enough to collect almost all of the plastic).

A huge 100-metre anchor will be 600 metres down, creating sufficient drag to slow down the clean-up system to a pace of 7cm per second.

The forces acting on the plastics - waves, winds, currents and so on - will also act on the system which means it will always be where the rubbish gathers.

"And now, because of the plastic magnet effect, we are able to clean up much more plastic, reducing clean-up time from ten years to five years."

The recovered plastic also has value, and the plan is to sell it to companies for reuse.

Eventually, the project will be self-sustaining, he says.

"Companies like furniture companies, toy companies, car companies - they can brand [their products] as being made out of ocean plastic."

This gargantuan clean-up could happen fast - even in one generation - and not just in the Pacific, Slat says.

"According to the current predictions, within the next 25 years, if we deploy 50 systems, the oceans could be clean again