Music Historian Graham Clark has just released a book on one of the unsung heroes of Kiwi music.

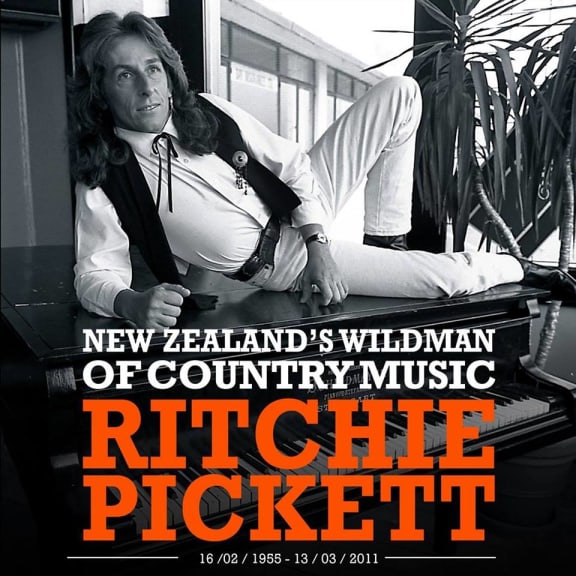

The story of Kiwi country music legend Ritchie Pickett Photo: Supplied

Waikato born Ritchie Pickett cut his teeth in 70s rock bands Graffiti and Think, toured the country with rock 'n' roller Tom Sharplin and became one of the stars of TV's That's Country in the 80s. Best known as the front-man for Waikato band The Inlaws, Pickett was a prolific song writer and a master at the piano.

Pickett died in 2011 at the age of 56, but his legend lives on in his music and this new book Thanks For The Clap.

Ritchie Pickett was the wild man of Kiwi country rock, who left behind a catalogue of hellraising tales, outrageous bon-mots and unfulfilled promise.

As well as being a chronicle of Pickett’s musical achievements, the new book by Graham Clark is, at his own admission “a story of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.” Some of that is reflected in its ribald title, Thanks For The Clap.

Clark explains: “Ritchie was in possession of a very dangerous tongue, a very sharp and finely honed weapon which he would use on any occasion. ‘Thanks for the clap’ was something that he would use to a burst of indifferent applause at the end of a song, if he didn’t think he was getting the attention he deserved.”

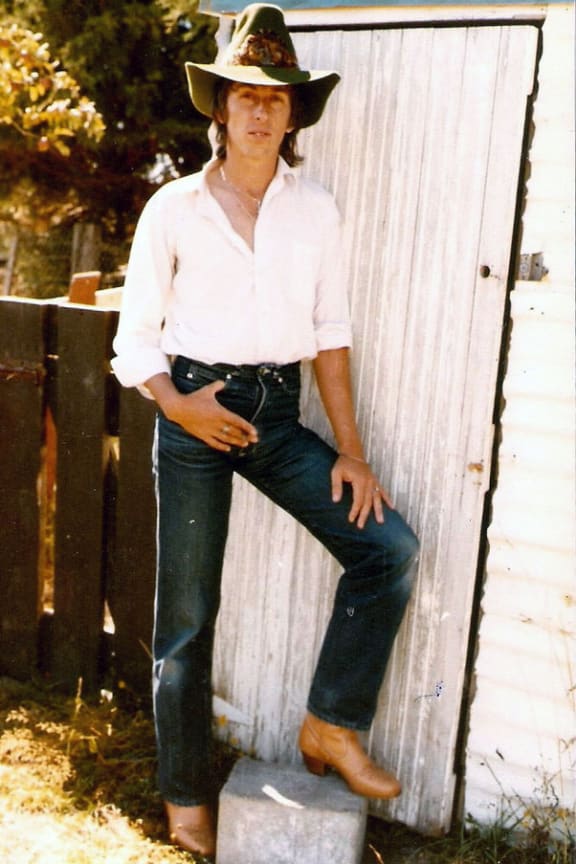

Ritchie Pickett in the early 1980s Photo: Courtesy Charmaine Pickett collection via AudioCulture

Another Pickettism: “Applause to the musician is like a banquet. Thanks for the fish and chips.”

Pickett's wildman reputation was well deserved. On one occasion at a country music festival, when Richie wasn’t getting the attention he thought he deserved, he doused the keyboards in lighter fuel and set it on fire.

In spite of his early love for honky tonk heroes like Hank Williams and Patsy Cline, the piano-pounding Pickett came to many peoples attention in the prog-rock era of the early 70s, when he joined Hamilton prog band Think. The group included guitarist Kevin Stanton, who would go on to find Australasian fame with Misex. (Stanton died in May this year.)

Though according to Clark, Pickett spent much of that decade “in denial of his country roots” he was eventually kicked out of Think for being ‘too country”.

This was followed by a spell in Australia, where he got heavily involved in the drug scene centred on the notorious ‘Mr Asia’. At one point Pickett was living with drug couriers Doug and Isobel Wilson, who were eventually murdered.

“His father had to go to Australia and get him out of a very tricky situation and bring him back to New Zealand. He was on death’s door. It’s lucky he survived.”

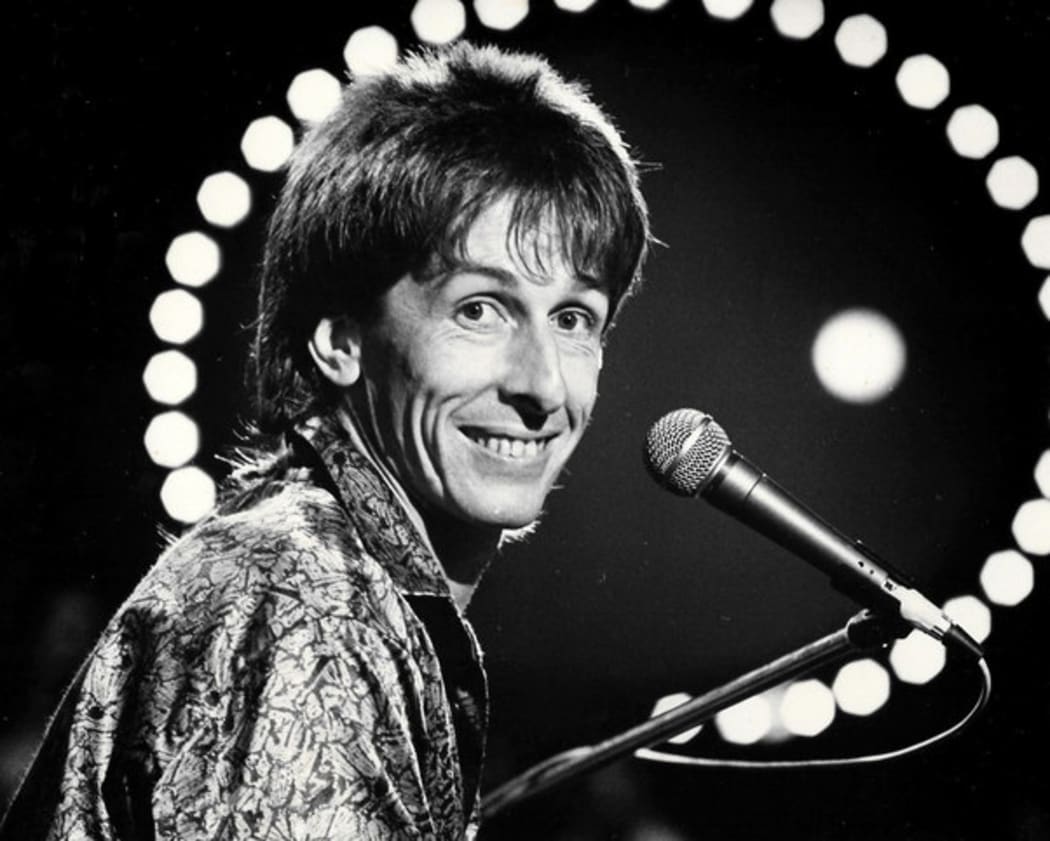

Back in Hamilton, trying to rehabilitate himself but not strong enough to pick up a guitar, he wound up seated at his first instrument, the piano, and rediscovered his country roots. It was around this time that his talent was spotted by Ray Columbus, who gave him a prominent role in the television series That’s Country.

Ritchie Pickett on the set of That’s Country, early 1980s Photo: via AudioCulture.

Though in 1984 he recorded with his band The Inlaws the classic New Zealand country rock album Gone For Water, the following decades saw many memorable live performances yet little in the way of recordings.

“Ritchie was a serial procrastinator,” says Clark. “He knew that he had something that was special. To me he always seemed like he was waiting for someone to come out of the wings and give him a recording contract or something.”

He came close a couple of times. There was talk of an American deal, and of Cher considering one of his songs.

Yet in the end his legacy is a handful of great original songs (try ‘3A.M. Hamilton Sunday Morning’), a kick-ass live album (The Wicked Piano-Pumping Pickett) and the memories of those who knew him or saw him in his glory.

His death in 2011, partly a consequence of his abusive lifestyle, was “a trainwreck… in slow motion.”

“I really can’t understand how it didn’t quite happen for him,” says Clark. “Just as he strove to achieve he also strove to sabotage himself. It was just the nature of the man.”