Dr Helen Taylor from the University of Otago has now created a website for people to bet on the speed of the hihi, or stitchbird, swimmers to raise money for the rare avians.

The hihi or stitch bird is a rare species and currently lives in only four areas in New Zealand.

Dr Taylor has been working with hihi for two years. Her previous research has looked at small populations and the effects of mating between relatives.

“We know that inbreeding can be problematic for male fertility across a wide range of mammals including plants, but no one has looked at it in birds before,” she says.

Dr Taylor says hihi used to be widespread, but populations diminished after human arrival. Reduced to a single population on Hauturu (Little Barrier Island) in the Hauraki Gulf, The Department of Conservation have now established six more populations on predator-free off shore islands and fenced sanctuaries.

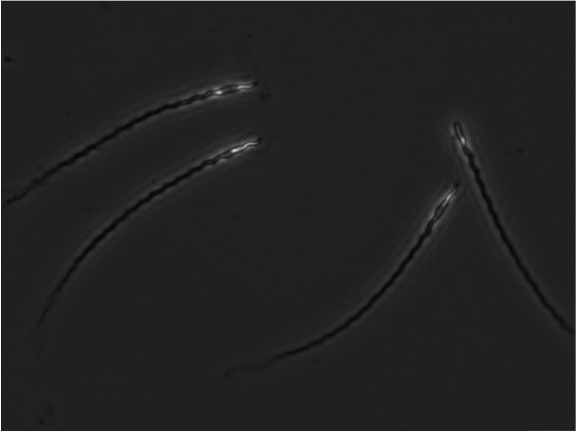

One of the problems with dwindling numbers of hihi is the lack of genetic diversity, and it is Dr Taylor’s task to look at the quality of hihi sperm to see how fast the sperm are swimming, and assess the length of the sperm a - longer sperm swim faster.

“We’re [also] looking for abnormalities, [for instance], does it have two heads, two tails [or] a missing head?” says Dr Taylor.

“[These] things are going to stop it [from] swimming at all. If it can’t swim, it can’t fertilise the egg.”

The big question next is: how is the sperm extracted from the birds?

Instead of a penis, male and female birds have what is called a cloaca, which is used for both reproduction and getting rid of waste.

“During mating season, the cloaca area in the males gets very swollen and we can use a technique called cloacal massage where we very gently squeeze side to side, and back to front and get a little bit of semen,” Dr Taylor says.

The process next is to put the collected semen under a microscope. But before heading to the physical lab it is important to inspect the semen while it is fresh and a mobile testing lab has been created to use on site when the researchers head out to remote locations.

“We need to keep the sperm warm, and if the sperm isn’t warm, it will die,” she says.

This mobile lab allows Dr Taylor to look at the swimming speed of the hihi sperm.

The team have collected sperm swimming speed data from 128 males from 4 sites and have set up a website to raise money for hihi conservation. Anyone can place a ten dollar bet on the bird they think has the fastest sperm.

To place your bet and help the race for the survival of the hihi head, to the Hihi sperm race website. The bet runs until 22 April.