Food industry groups spend massive amounts on research to support health claims, producing biased science, Professor Marion Nestle says.

Photo: RNZ / Richard Tindiller

Prof Nestle has made it her mission over the last 50 years to shine a light on food politics and what she says is questionable dietary science that cooks the books in favour of food and beverage companies that pay for research.

Food researcher Marion Nestle. Photo: Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons

She has written a book about it: Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat.

She tells Afternoons' Jesse Mulligan she's always been interested in how the food industry influences nutrition and health.

"In the United States, the food and beverage and alcohol industries together spend about $US30 billion a year on marketing their products.

"I'd like to get those numbers smaller - in 2016 for example the Kellogg's company spent $30m just in the United States to advertise pop tarts.

Photo: supplied

"That money was just the money that was spent through advertising agencies for pop tarts. That's one product.

"Nowhere is there a federal agency that spends anywhere near that amount of money on nutrition or health education for the entire population.

If the marketing is done well, you won't even see it.

"You're not supposed to notice it, it's just supposed to hit you in some emotional way that you react to unconsciously without really realising what's going on."

Those efforts have been effective, she says, and it's amazing how food marketing is largely left out of discussions about health and food choices.

"One of the things I like to do is go on Google images and look for diagrams of influences on food choice. There are dozens of these diagrams and they talk about taste preference, religious preference, peer pressure, cultural preference - all kinds of things that influence food choice - they almost never mention food industry marketing.

"As if food choices were made in an environment that was devoid of advertising marketing and efforts to sell food everywhere."

She says funding research is one of the ways food companies try to get people to buy more of their products.

"As I'm fond of saying, we have available in the United States an average of 4000 calories a day per capita - and that's men, women, little tiny babies, ancient old people - 4000 calories is roughly twice what the country needs."

Coca-Cola and the Clinton emails

The response to Prof Nestle's 2015 book Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning) offers a political and personal example of how the food industry tries to manipulate research and reporting on it.

Hillary Clinton speaking during a Colorado Democratic party rally in Colorado in October. Photo: AFP

"I was totally shocked, I was reading about the Russians hacking the emails of Hillary Clinton's campaign advisers. It never occurred to me that I would have anything to do with it, but I started getting messages from people saying 'Marion, you're in these emails'.

She says she had been giving talks about her book, which had just been released.

"An adviser to Hillary Clinton who travelled with her was also a consultant with Coca-Cola getting $7000 a month for her services, and so her emails to the vice president of Coca-Cola were picked up as part of this.

"I was just astonished to see the notes from my talk - excellent notes by the way - passed up through the chain of command and ending up hacked by the Russians.

"One insight was that they're keeping an eye on people all over the world who might be saying something critical, but the emails also expose Coca-Cola executives' efforts to influence reporters who are writing about research and also to influence researchers."

She says Coca-Cola was funding studies, aiming to show three specific things:

-

That sugary beverages have nothing to do with obesity and type-2 diabetes.

-

That research linking sugar-sweetened beverages to obesity or type-2 diabetes is flawed and not worth paying attention to.

-

That physical activity is more important than anything else in maintaining body weight.

Photo: RNZ / Diego Opatowski

The global energy balance network (GEBN) is an example of this Prof Nestle says. The GEBN was group of researchers who argued that physical activity was a more important factor in body weight than what you ate - the now defunct group was funded by Coca Cola.

"These investigators [researchers] neglected to mention that they were funded by Coca-Cola, so the exposure of that connection by the New York Times caused an absolute scandal."

The tobacco playbook

Prof Nestle says she feels a little uncomfortable picking on Coca-Cola.

"Because - as I explain in my book - food companies do this across the board. It's just that Coca-Cola got caught because of its exposure of its emails."

She says that while writing Soda Politics she noticed how prevalent industry-funded research was elsewhere.

"So, I was paying attention to Coca-Cola funded studies, but then I noticed that there were many studies that were coming up - one after another, after another - and I thought 'that study has to be sponsored by some food company'.

Photo: Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons

"There's a study that came out a few months ago that said that mangoes were better ... at treating constipation than fibre supplements.

"I thought 'who would do a study like that, I wonder who funded it': bingo - the National Mango Board.

"More recently, a study about chewing gum being an excellent vehicle for getting vitamins into your body, and I thought 'oh, come on, you have to be kidding me, who would do this study, who funded this?' - well, the company that makes vitamin supplemented chewing gum, of course."

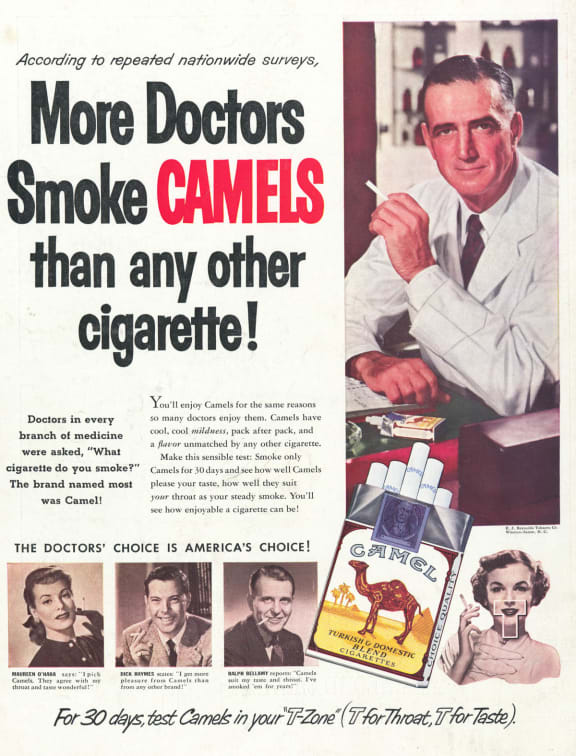

Cigarette advertisement, 1952. Photo: Stanford School of Medicine

These industry groups are simply taking pages out of what she calls the tobacco playbook, beginning with the cast-out of good science.

"The tobacco industry, years ago, when confronted with preliminary - and better than preliminary - evidence that cigarette smoking was associated with lung cancer said all they had to do was to cast out all the science: to create enough doubt so that people would continue to smoke.

"They did that very effectively in the United States for about 50 years before things tightened up around them."

She says other elements of the playbook are:

- Co-opt scientists

- Get scientists to argue for you that the science isn't there

- Create front groups that also argue about the science

- Promote self-regulation

- Promote personal responsibility as the fundamental issue

- Use the courts to challenge critics and unfavorable regulations

"And then to do a lot of lobbying behind the scenes. Funding research is absolutely part of that - and the food industry does all of those things."

The bias of science and the science of bias

People who do the studies say the conduct of their science is fine - and it well may be, Prof Nestle admits - but there's also evidence that funding does have an effect on the results.

"The funding effect is the observation that the great majority of industry-funded research comes out with results favourable to the sponsors' interests," she says.

"Bias can occur at any stage in the research process, but Lisa Bero and her colleagues from the University of Sydney have demonstrated that the place that bias is most likely to occur is in the framing of the research question."

She says research that looks at the effects of diet in general is very different to research looking at whether a particular product has a specific health benefit.

"This is research that's aimed at getting a marketing advantage for the product," she says.

For example, there was one "very meticulously designed and carried out study" that showed rats that were fed pomegranate juice had higher levels of antioxidants.

"I thought 'of course … all fruits and vegetables have antioxidants, if you feed any fruit or vegetable to a rat it's going to have higher levels of antioxidants - but compared to what?

"And, why would you care when there's not much evidence that antioxidants do very much for people who are healthy anyway."

"The pomegranate people are especially interesting because they put so much money into research - $35 million, I think. That's a lot."

The pomegranate company POM Wonderful responded to Prof Nestle's challenge, by saying that "comparing the health benefits of our product to other juices is not a key objective of our extensive research program".

"To which I would ask, 'if you're selling 'health,' why wouldn't it be?'," the professor says.

Another example is macadamia nuts.

"The FDA approved what it calls a qualified health claim for macadamia nuts and I should tell you I adore macadamia nuts … The FDA essentially allowed them to use a claim that I thought was so hilariously funny.

The "qualified health claim" the FDA allowed was:

"Supportive but not conclusive research shows that eating 1.5 ounces per day of macadamia nuts as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, and not resulting in increased intake of saturated fat or calories, may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease."

Approval of that convoluted, largely redundant message led to a headline the day after it was approved: "Go nuts folks, FDA declares macadamia nuts heart-healthy".

Prof Nestle says consuming a very wide variety of relatively unprocessed foods is good dietary advice.

"So, yeah, eat fruits and vegetables ... but is it really better to eat pomegranates than some other fruit? I don't think so."

To regulate or not to regulate

It's the most highly processed products that are the most profitable, she says.

"So, there's an inherent contradiction there between public health and the economic interest of food companies.

"Their job is not to be concerned about public health, it's to sell food products - as many, to as many people as possible, at the highest cost they can get away with charging."

She says that means there's no point getting the companies to try to work together to make food healthier and less processed - and argues it would be better simply to introduce regulations.

"We do have one example of a voluntary food situation working, and that was in Britain, which got food companies to agree across the board to reduce the sodium in their products.

"They did, and stroke incidence and prevalence decreased - it was very effective - but now a new government has come in and kind of let that go, but that's a very rare example.

"What we've seen in the United States is that nobody wants to go first - it would be much easier for food companies if there were regulations and then everyone would be on the same level playing field."

Professor Marion Nestle is the Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University. She is also a professor of Sociology at NYU and a visiting professor of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University.