Five months without work, scant food and the whole nation against you... Katy Gosset hears a first-hand account of the long battle that was the 1951 Waterfront Dispute.

Baden Norris Photo: Katy Gosset/RNZ

Subscribe free to Are We There Yet. On iPhones: iTunes, RadioPublic or Spotify. On Android phones: RadioPublic or Stitcher.

It was 151 days, a long 151 days and some men who lived through it will never forget it…

Baden Norris is one of them.

"It was my blackest period of my life because I had no money, or very little. I had a daughter [who] was in hospital with melanoma. You couldn't get another job. You'd be pretty unpopular if you did."

So how did it all begin?

Baden describes himself as “Lyttelton material”, born and bred in the little port town like his father, his grandfather and great-grandfather before him.

“It was the centre of the universe when I was a child. I never wanted to be anywhere else.”

He worked in a factory at 13, went to sea at 15 and then, in his 20s, being "Lyttelton material" led him to work on the wharves.

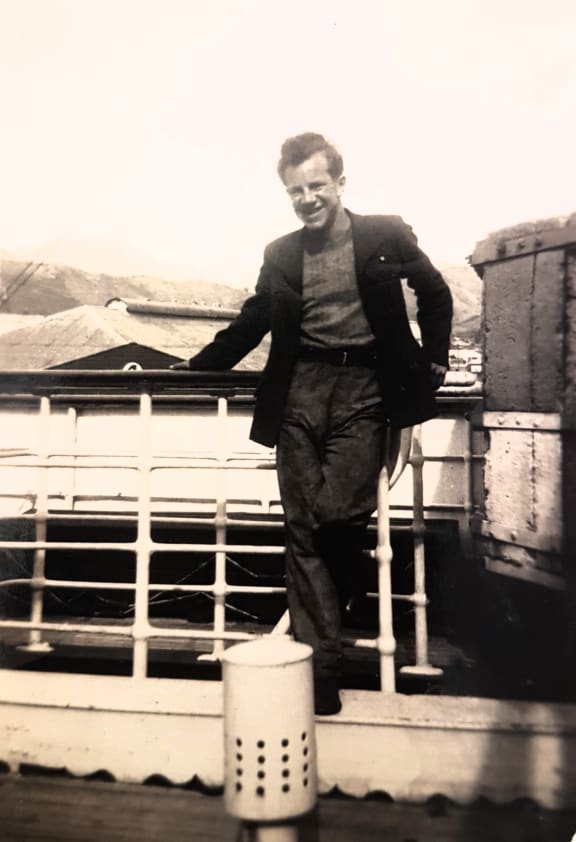

Baden Norris on the waterfront Photo: Supplied

Being a watersider wasn’t an aspiration, as such, but, by then Baden was married, with a child, and money had become more important.

And on the waterfront, a man could make good money, not because the job was so well paid, but because there was plenty of overtime.

It was also a place where Baden found camaraderie among like-minded types who shared his love of the sea.

"Companionship.. there was an awful variety of men on the waterfront [with] interesting backgrounds, particularly of maritime worlds. You almost joined a club."

But trouble was brewing on the wharves.

Strike or Lockout?

The union movement had become divided. By 1951 the waterfront workers supported the Trade Union Congress, a group that had splintered away from the main union, the Federation of Labour.

New Zealand was emerging from the Second World War and the Government offered a wage increase to workers.

Except it wasn't across the board.

Baden Norris said wharfies had to apply to a separate tribunal for the pay hike and it was turned down, on the basis that the workers were already well paid.

But he said this was only because they worked so many overtime hours.

"So [the workers] said "We will refuse overtime until we get some satisfaction" and, of course, that's how it all started."

But their employers responded that, if the men would not work overtime, they couldn’t work at all.

The ship owners, and later the Government, called the dispute a strike but, to the workers, it was a lockout.

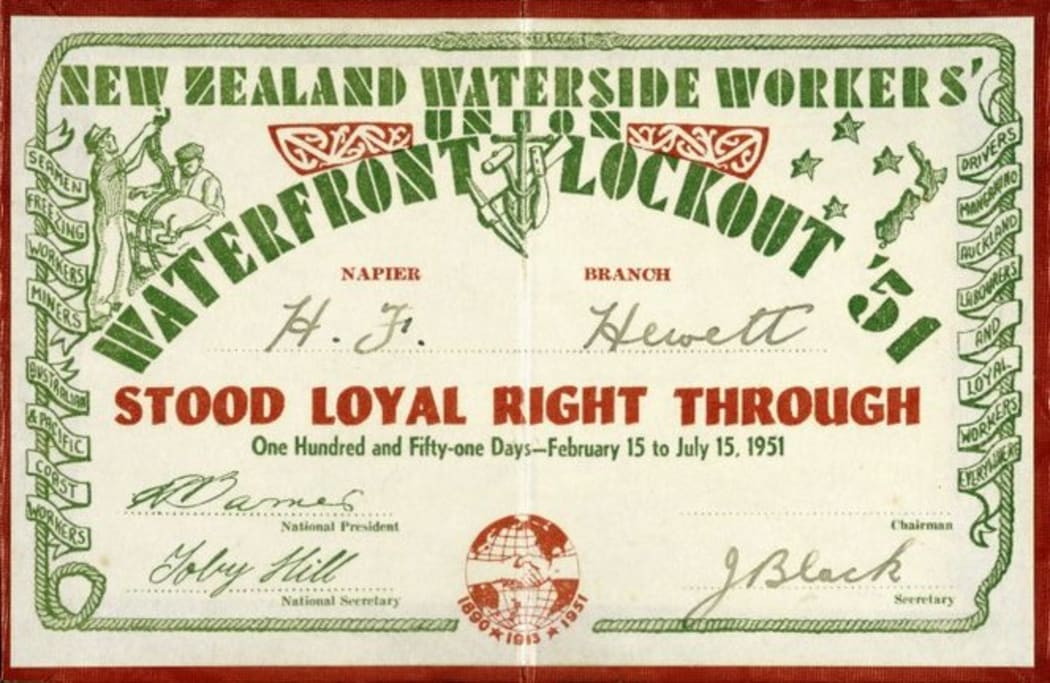

Photo: New Zealand Waterside Workers' Union : [H F Hewett], Alexander Turnball Library

A State of Emergency

On February 22, 1951, the Prime Minister, Sidney Holland, announced a State of Emergency.

He told the nation "A small group of men possessing great power in our industrial system declared war on the people by calling a strike in one of our principal key industries."

With the state of emergency came new and stringent regulations and, over time, Baden Norris and his colleagues found these were beginning to take a toll.

"It was illegal, for instance, for a mother to feed her son. One would think that would be impossible but it wasn't. The law stated that you weren't allowed to."

Baden Norris in Lyttelton Photo: Supplied

Regulations also meant the workers were constantly watched and so they couldn't risk collecting the food they had stored at their depot. Family members had to be sent instead.

"I always feel sad that my dear old mother would have to sneak up from the depot in a big overcoat so that nobody could see what she was carrying - that really saddened me - tough times."

Baden Norris said the police also had wide powers to stop and search people. He recalled on one occasion a man was jailed for several weeks after he objected to having his belongings searched.

"Those sort of things, you wouldn't think would have happened in New Zealand."

But the most challenging regulation for the Norris family was an inability to travel while their daughter lay sick in a Christchurch Hospital.

"We weren't allowed to leave the port - that was the darkest moment, when you couldn't even do what any child should expect: her parents coming in as visitors."

Fortunately, an aunt gave them money to take the train to visit their daughter and she made a full recovery.

“Tough Times”

Still, day to day living was hard. The family kept fowls and luckily they laid every day.

"I also had a good crop of potatoes so we largely survived on eggs and chips."

Meanwhile, the watersiders still met regularly to organise food distribution. Some farmers offered them crops in return for unpaid work in their paddocks.

The workers also had teams of slaughtermen who distributed meat amongst the affected families, although a hierarchy still existed.

Baden, who had worked at the wharves for just five months before the dispute, was a "newcomer" and eligible only for a "flap", a cheaper cut of meat.

Still, the men helped each other. About 8000 watersiders were out of work around the country but 4000 more were miners, freezing workers, drivers and other workers who had gone out in sympathy with them.

Baden said, when there was spare food this was taken over to the West Coast "in the "dead of night" to share with the miners. The watersiders then brought back coal for elderly members of their community.

People queuing outside the Gear Meat Company in April 1951. It's thought this was as a result of the Waterfront Dispute. Photo: Evening Post Newspaper, Alexander Turnball LIbrary

A Town Divided

And yet the hardest part was being cut off from their own communities.

The dispute meant goods weren't being unloaded from the ports as quickly and that led to shortages for both shops and households.

The emergency regulations imposed by the Government had also effectively gagged the media so the waterfront workers' side of the story wasn't being told.

"Nothing was to be printed that supported the watersiders at all and the newspapers took it like a lamb. One might have thought they'd object to the fact that their media's being interfered with, but they didn't."

Baden Norris said the impact of this often, one-sided reporting left the port town "split right down the middle".

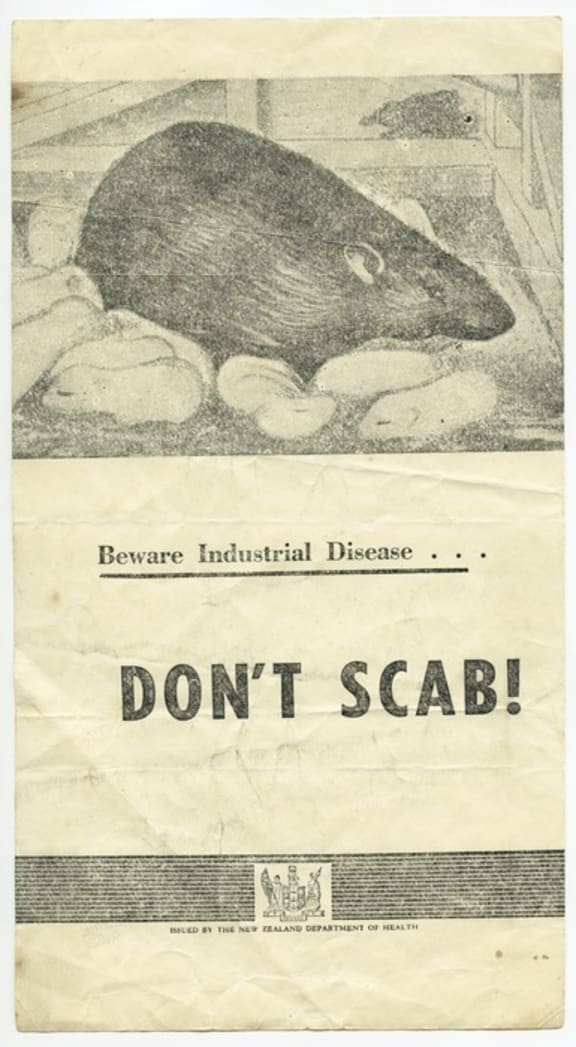

A flier issued by industrial unions during the waterfront strike in 1951 Photo: Alexander Fry, Alexander Turnball Library

Families too were affected as the workers' children were in the same school classes as youngsters whose parents had taken the men's jobs.

"Even [at] school, the annual picnic had to be postponed because of the bitterness."

And he believed that rancour lingered on in the township.

"It's still there in Lyttelton. You hear a lot of people talking about someone and they'll say "Oh, yeah, but his father scabbed."

A Return to Work

In the end, in mid-July, worn down, the men gave in and returned to work on the Government's terms.

But Baden Norris says many workers, in particular, the many returned servicemen on the waterfront, struggled to move on.

"A lot of men thought that they've done their duty but they were branded by the Government as enemies of the state. That's what saddened me mainly. Certainly, a lot of the ex-servicemen never got over that."

And Baden admits he's also struggled to get over it, regretting that he can't let go of what happened.

"A lot of people say "Get a life. Forget all about that", but I can't forget it. I'd like to be able to but, deep in my head, I'm still bitter."

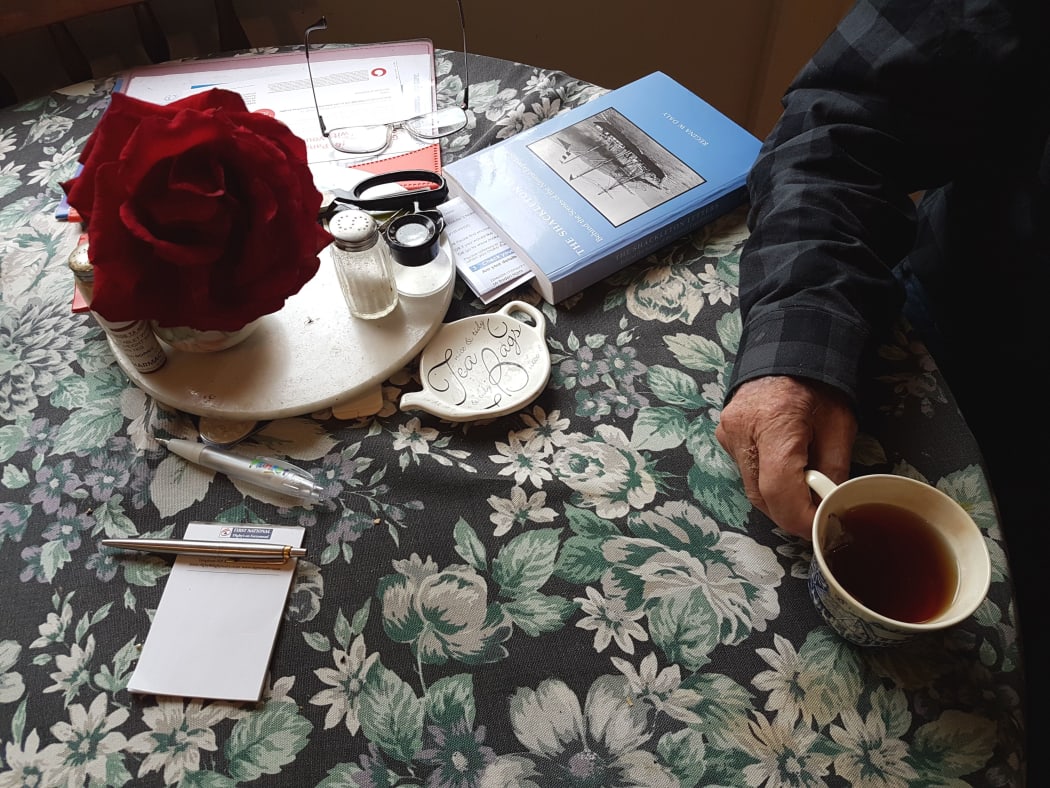

Despite those regrets, Baden Norris has lived a full life. He has written books, travelled widely and become an authority on Antarctica, visiting the ice on numerous occasions.

Photo: Katy Gosset/RNZ

And now, in his nineties, he is still "Lyttelton material". An account of Shackleton’s journey lies on the breakfast table, prints of ships line the walls.

And memories of the Waterfront Dispute are there too, the less fond ones mingled with the reminder that tough times can also bring out the best in people.

"One man, I never knew who he was, came up to shake my hand in London Street in Lyttelton and when I opened my hand there was a ten shilling note he had pressed into it.

He took off into the crowd without me even [able] to thank him."

And throughout that challenging period there were many other small acts of kindness, a bag of fruit or other items of food left at his gate.

"They may not have sympathised with what you were doing but they just couldn't see you starve."

"It had its darkest moments but it also had its brightest moments."

And, as he looks back, he has put the experience in some context.

“It’s a bit like war. It's the most exciting period of your life if you happen to be unfortunate enough to be participating in it but I'd never recommend it to anyone."

Baden Norris Photo: Katy Gosset/RNZ