An Australian court has ruled in favour of a journalist who claimed covering crime and court cases exposed her to life-long trauma. Mediawatch asks veteran crime reporter Gary Tippet, who gave evidence in the trial, and long-serving RNZ court reporter Ann Marie May about the special stresses of covering crime and the courts.

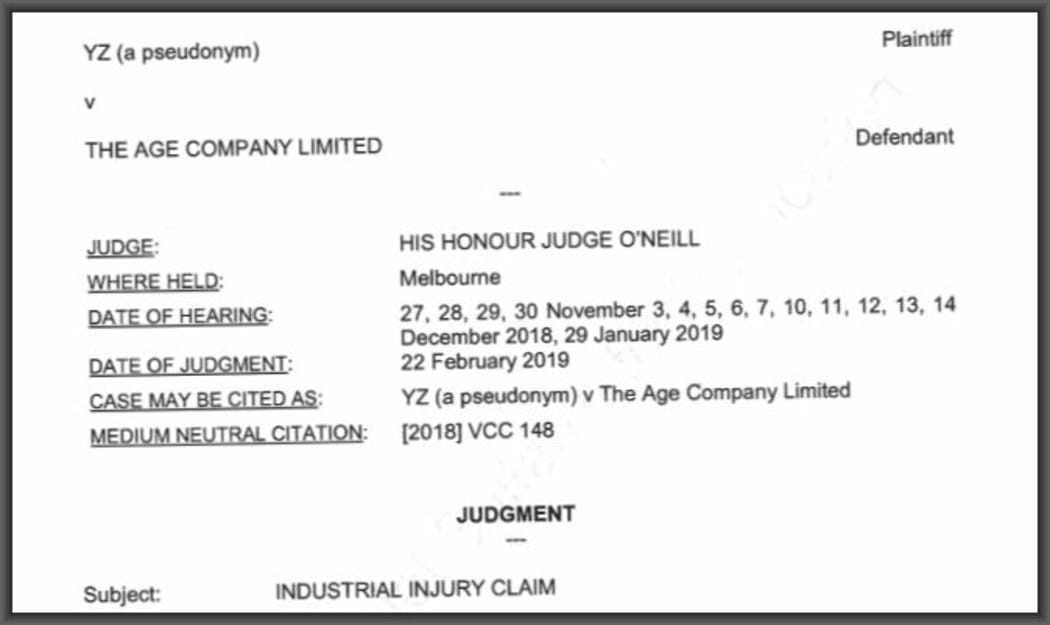

The Victorian court judgment which found in favour of a former journalist. Photo: screenshot

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is fairly well-known these days - so well known it's often referred to by its initials alone.

PTSD is most often used to describe the after-effects of war and disaster on people who find it impossible to live a normal life long after their initial exposure to the stresses.

It’s only in recent years that media companies have begun to address the mental health of employees repeatedly exposed to distressing scenes and stressful circumstances, often with no prior training in how to cope.

And it may end up costing them.

Last week, a court in Australia ruled - for the first time in that country - a journalist’s employer was liable for the effects of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and depression.

A newspaper crime and court reporter - identified only as YZ in the judgement - was awarded $A180,000 in damages after a trial lasting three weeks.

For almost a decade until she volunteered for redundancy in 2013, she worked for Melbourne’s main daily paper The Age - published by Fairfax Media, the parent company of the Stuff chain which publishes most of the papers in this country.

Judge Chris O'Neill ruled that "she is significantly scarred because of her work at The Age."

"She did not receive any training over the period as a crime reporter about how to deal with death and tragedy, save for one day of a two-day training course. The second day of the course dealt with post-traumatic stress, but she was called out to attend a murder scene," the judgement said.

The court was told the reporter repeatedly asked superiors for support in the wake of stressful stories.

One was the death of four-year-old Darcey Freeman, who was thrown off a bridge by her father in 2009. The court heard she requested a transfer away from crime reporting the day after that and was given a court reporting role a year later.

Her mental condition worsened covering murder trials, including that of Darcey's father, the judgement said.

"She went back to the newsroom and said “I’m done, I can’t do this anymore. She said she felt she was surrounded by death and misery. She was in tears in the newsroom but completed writing the story. To this point, she had attended the scenes of about thirty-two murders.

Despite her evidence that she was obviously distressed in the presence of editors at the news desk and other Age staff, rarely did anyone inquire as to her welfare.

The judge said there was a "clear indication" an underlying psychological disorder was emerging.

But you won't find any reports about this trial - or this potentially precedent-setting ruling - in The Age or any other paper published by the company.

Gary Tippet, former crime reporter for Melbourne newspaper The Age. Photo: supplied

Gary Tippet worked alongside the reporter known as YZ at The Age.

He’s covered a good deal of violence and trauma too. He won Australia's prestigious Walkley Award for a harrowing account of an abused child who killed his molester with an axe years later.

During the trial he gave evidence that 10 years ago he had submitted a report to the powers that be at The Age urging them to act on the need to support stressed journalists.

"I pointed out then, when I made the report, this could end in litigation and be very financially damaging. We got virtually no feedback. We wanted the management sending people on these jobs to engage with us," he said.

"I understand (this ruling) to be a world-first and a precedent for media companies to be aware of - but I'm not confident they will," he told Mediawatch.

Mr Tippet is now a freelance writer who has also studied the effect of trauma on journalists and what media companies should do about it.

"(YZ) was getting sent to terrible jobs even when she was expressing the fact that she was suffering from the effects of the things that she saw," he said.

Mr Tippet began as a journalist back in the 1970s when he says newsrooms were full of reporters who had been-there-and-done-that in Vietnam without any knowledge of the effects of trauma and stress, let alone effective support or treatment.

Back in 2012, he told Mediawatch he got no preparation when he started out as a cadet just out of school:

“I was put on the police rounds as a cadet. They said 'there’s a man missing in a forest' and by the time we got there, they’d found a body. As a young person you cover lots of road accidents and you knock on people’s doors and do the ‘death knock’. Being exposed to this stuff is like water torture. Drip by drip it does you harm. We know that now.”

A photojournalist at the same paper did not succeed with a similar action in 2012.

Is it possible that reporter YZ was simply not suited to the job of reporting crime, and it doesn't mean most reporters would not be affected in the same way?

"No," Mr Tippet said emphatically.

Photo: supplied

"The level of traumatic stress covering crime disaster and murder is significant. That's not to say most people aren't resilient or can't cope with it but it's not an outlier," he told Mediawatch.

"The simple answer is provide the training at the beginning of their careers so they know what they are in for," he said.

Should media here pay attention to this ruling?

"To do court [reporting] as a long-time thing you need to be thick-skinned," said RNZ’s long-serving chief court reporter Ann Marie May.

"You are seeing what the jury sees, including graphic crime scene pictures of things like a body badly damaged in an attack," she said.

She grew a thick skin straight out of school working as a stenographer in court before training as a journalist. Her first case involved six gang members on trial for rape.

"The things they had done were not things they told young ladies about at Sacred Heart College," she told Mediawatch.

"I became accustomed to hearing that stuff at an early age," she said.

She told Mediawatch she never felt she needed to be taken off court reporting duty because of the distressing nature of the cases.

But she said there are two court cases she has not been able to forget.

One was a domestic incident in which a family including small children were violently attacked by their father armed with a knife. Only after finishing a report for Checkpoint, she was moved to tears

"I just felt so awful because of the children. The chief reporter told me: 'Go home - now'," she said.

Another case she covered where a man was tried for murder reappeared in a nightmare.

If media companies are found liable for damages in more cases where reporters have suffered PTSD and trauma, it may make them more risk averse.

Is it possible that reporters who 'do the right thing' and raise the alarm when they suffer symptoms of stress could end up being sidelined from big stories because employers fear liability?

"I don't think this will open up the floodgates - or that reporters will say they've had a mental trauma and seek to be paid $180,000," Ann Marie May said.

"I think people just need to be more aware and listen," she told Mediawatch,