Director Sophie Fiennes spent five years making Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami - a film that gets close to the Jamaican icon, both on stage and off.

Grace Jones Photo: supplied

“I think there’s an honesty, and there’s a generosity in allowing herself to be filmed in such an unguarded way”, says Sophie Fiennes. “She’s not in control of those moments.”

This is Grace Jones; raw, complicated, unpredictable. Yes, there’s that fierce Jones we know, the one who tells Robbie Shakespeare [of Sly and Robbie, the most famous reggae rhythm section in the world] that she’s “pissed off” at him. The straight-up Jones who tells a French TV producer off for giving her a tacky set and babydoll dancers for a performance. Who shouts at her manager for not sorting things out.

But we also see her in vulnerable moments, naked - sometimes literally so. We see the world as she sees it, trying to sketch a Parisian skyline, running up a hill to catch the last of the Jamaican sunrise with her camera, sucking the life out of a plate of oysters.

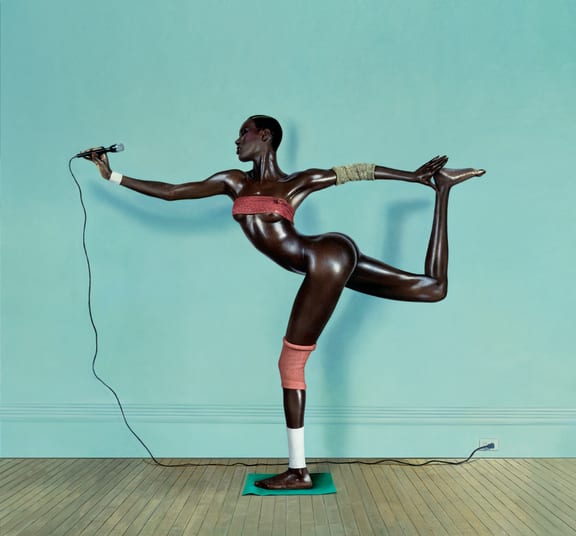

Grace Jones - Island Life cover, 1985 Photo: Jean-Paul Goude

It makes a stark contrast to the Grace Jones we see on stage, or in the iconic photos that her photographer ex-partner (and father of her only child) Jean-Paul Goude presents - the armoured, androgynous warrior woman.

“That was what affected me, was when I realised that she was challenging herself to show that part of herself that she’d never shown," Fiennes says.

"There was a kind of armour, and a performative pleasure in what she has created of herself. She’s her own Svengali.”

Jones wanted to be an actress - and had some notable roles in the 80s, as a stripper vampire queen in Vamp and as a warrior in Conan The Destroyer alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger, and as scary Bond henchwoman May Day, but it’s the music stage where her theatricality has always played out best.

As Jones purrs over a champagne breakfast in the film: “If the lights should go out, if the electricity fails, I can still perform, and hold the audience, in the dark.”

For Grace Jones: Bloodlight And Bami, Fiennes knew she wanted to film her in concert, building a specially designed theatre set, where Jones, in her ornate headpieces, prowls, strides, kicks and sashays around the stage. At one stage she even hula hoops, all with 6 inch stilettos on. It’s pretty impressive, for someone approaching 70.

Jones lives in the moment when she’s performing, and this is mirrored in the documentary. There are no talking heads discussing outrageous incidents in her past (and there are a few), no ex-partners or other musicians talking about how they see her, no old footage from the height of her success.

“There’s something hermetic about everything being in the present moment. As soon as you step out of that, you break that magical contact with the Grace that’s right in front of you.”

But the past is all there, and obviously plays a big part in Jones' life.

There is a photo shoot with Jean-Paul Goude, with whom Jones has remained close.

Fiennes says “I always think it’s funny when men see that scene, and they say ‘what, that small ugly little old guy was the person that made her buckle at the knees?”

Grace Jones in Jamaica Photo: still from Bloodlight and Bami

“Their collaboration was the erotic motive in that relationship. He took a lot of the credit for it, and I think increasingly now people are seeing that Grace brought a lot to it herself.

"But the thing that interested me was his gaze, the way that he’s looking at her, the way that she understands he will see her, and what she can be in front of his camera - what she can become, and the tension in that - the erotics of that.”

During a family reunion in Jamaica, there is talk of the beatings Jones and her siblings received at the hands of Mas P, their minister step-grandfather. And though she embodies the ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ adage, we see her hurt, we see that she is an abuse survivor, and that she carries that weight.

“On that trip, she was trying to see if she could confront, with her parents, that childhood. But actually they weren’t able to go with her, or her brothers, or talk about it. So there is something that is impossible to heal.”

It’s obvious that Jones likes to party. In her memoir, published in 2015, she talks about the disco being a place to lose yourself to find yourself.

“That hedonistic, dionysiac, bacchanalian kind of - you know, letting rip, is a big part of her personality.” Fiennes says.

Fiennes spent five years filming, on and off, and two years on the edit. Unsurprisingly, she says she’s become very close to Jones. “She said that I was her soul sister. She’s good fun to be with, too. She is intense, but I’m quite intense too, so we’re quite well matched.”

Sophie Fiennes on location. Photo: Remko Schnorr_

It was Jones that proposed the documentary to Fiennes, after they met at the premiere of the film she’d made about Jones' brother Noel Jones, the charismatic leader of a pentecostal church. “She totally understood the film. We immediately had a rich and intense conversation, where she talked about the culture she experienced. I remember her saying to me ‘Honey, I am church burnt. To a cinder. To a crrrrisp.’

It’s an example of Jones' inventive way with language. She takes joy in it’s delivery, and we hear her accent slip from thick Jamaican patois, to coarse cockney swearing, to purring Parisian.

Despite the close relationship, Fiennes says she could never claim to really know Jones.

“For me, the proper philosophical insight that I felt from the footage, that I took into how I shaped the film, is that we are all much broader in our personalities and who we are than we’re expected to be, or we want to pretend we are.

"Different situations bring out different parts of ourselves, so I could never claim to know what an unpredictable situation could produce in Grace. I could say that about people I’ve known my whole life, we can never fully know anybody. It’s a challenge to know even oneself.”

Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami plays at the Dome Cinema (Gisborne) on 8 March and the Rialto Dunedin and Rialto Newmarket (Auckland) on 9 March.

Grace Jones and her band play Queenstown Friday 2 March and Auckland City Limits Festival on 3 March.