Lionel Carter first started exploring the oceans using sextants and sonar - now he's using satellite scanning and computer analysis.

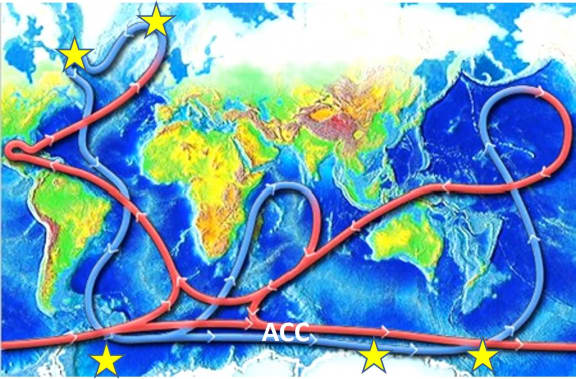

He began his career working out the boundaries of New Zealand's exclusive economic zones and was involved in the discovery of the Pacific Deep Western Boundary current - the world's largest deep sea current.

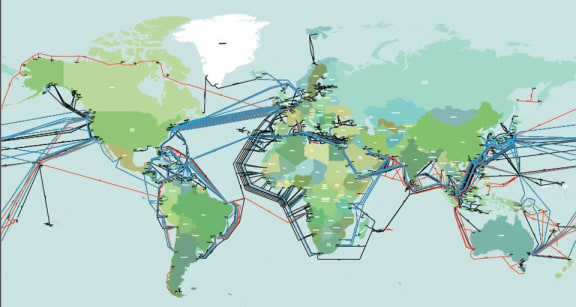

Right now he's involved in the International Cable Protection Committee working out how to prevent undersea landslides and submarine volcanoes from cutting the cables which reach across the ocean floor.

Read an edited excerpt of the interview below:

When were these cables first laid?

New Zealand was involved in one of the early lays, that was the Trans-Tasman cable, linking the West coast of the north island with Sydney. We were doing that work in 1988, so these cables really came to the fore in the late 1980s and since then they under pin the internet.

How do you lay the cables in the first place?

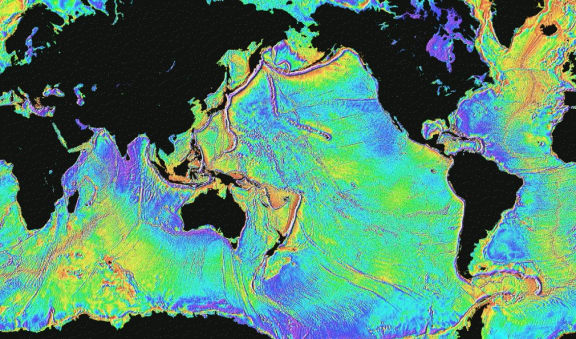

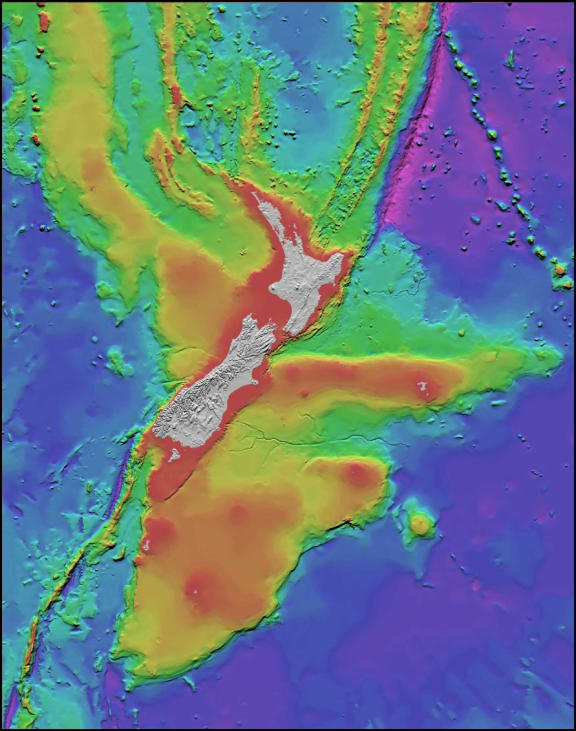

They’re laid out with great care. Let’s say we’re going to lay a cable from the West Coast to Sydney. The first thing we do is a route survey and we do that on the data we have available and then we take a ship out and map the seabed upon a route suitable for cables. Satellite mapping and these mapping systems that are now on ships where they can map 10, 20 kilometres of the seabed. So we’ve mapped the seabed and we decide where the cable should go. The cable ship comes out with the cable coiled within several tanks on the vessel. Then the vessel starts out at the West Coast of the North Island, lays it across the continental shelf. Shallow water. Then we go down to a four-five kilometres depth. Laying it all the time but laying it under tension so you don’t form like a ball of knitting on the seabed. So we run steaming along at about two-three knots and then we arrive back in Sydney. So it’s quite straightforward, but the key thing is picking the route. What are we avoiding? Are we avoiding underwater volcanoes, are we avoiding fault lines? That’s where the geology comes in – picking the safest route.

When we’re looking at the directions that these cables are going in; across to Australia and across to the United States as well, what are they crossing when we’re talking about volcanoes and other activities.

This is where the fun comes in. I am sure the listeners have heard of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Lots of earthquakes and volcanic activity. Just look at the cities around that Pacific Rim. You’re looking at Tokyo, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Vancouver, New Zealand. You have to go through hazardous zones to serve these major metropolises.

Those cables in the Mediterranean, Caribbean and the Pacific, they do have to cross these tectonic plate boundaries. The boundaries are colliding, they generate earthquakes, landslides, volcanic activity… so these cables we do have to find the best way through these hazardous zones.

What are the greatest risks to these cables?

The greatest risk is us. When you’re on the continental shelf in waters of say, 200 metres and shallower, the key antagonists are bottom trawling, and ships anchors. That accounts for about 70 percent of cable faults. So when this thread comes into the shallow water, they wrap steel wire around it to give it extra protection and they bury them. If you’re in Singapore, they bury them at something like 10 metres below the seabed. But most likely they’ll be less than 3 metres below the seabed.

When you go into the deep ocean, that’s when we’re getting into the natural hazards. The big risks there are submarine landslides and a tabidity current. As these landslides take off they mix with water, so you’ve got what is more or less a muddy slurry taking off down the slope and as it goes down the slope it pings these cables one after the other.

We had an event in 1929. About 22 cables were broken in the North Atlantic and that was an indicator that the seabed was far from ‘still waters run deep’. It was considerably mobile.