Wildlife poachers are usually poor and desperate to risk life and limb, while those who sell the products have little chance of getting caught, the author of a book on illegal wildlife trade says.

John Pameri, head of the security at the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in central Kenya, holds a Rhino tusk his team took from a Rhino that was shot dead by poachers earlier in the week at the security headquarters on December 9, 2010. Photo: AFP PHOTO / ROBERTO SCHMIDT

US science journalist Rachel Love Nuwer has spent a decade covering the topic of poaching.

Her book Poached is the story of how she pursued the poachers, their associates, and the people who buy their illegal goods, as well as the activists that try to stop them.

Pyramid of death profits

Nuwer says it's the people at the top of the chain who profit the most.

You can think of criminal enterprises -whether it's drugs or wildlife crime - as a pyramid.

"At the bottom you've got ... in this case the poachers: these are oftentimes poor men living around national parks or other protected areas, they're paid the very least, they might get $100 to kill an elephant.

"By the time it moves up the chain to the bosses in Asia controlling this, to the people selling it, you're talking about something that's worth a lot, lot more.

"There's very little risk of getting caught."

She says the scale of poaching is "massive".

Indian forestry officials on an elephant look at a one-horn rhino as they conduct a census of the endangered species at the Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary, some 45km from Guwahati, March 18, 2018. Photo: Biju BORO / AFP

"It's estimated to be worth up to $23 billion annually and it ranks [fourth] just behind drugs, arms and human trafficking in terms of the world's biggest contraband industries."

The trade is also on the rise, she says.

"Since the 1990s and 2000s, wealth in particular countries - especially China and Vietnam have increased, which enables a lot more people to be able to afford products like ivory or rhino horn.

"These were products with a really long history in these countries but ones that were always out of reach for a majority of people.

"Now that more people can afford them, yes, trade is picking up."

Rare animal parts in demand

The demand for these products is based on a range of different needs.

"It's extremely multifaceted. You have everything from people shopping for jewelry - ivory jewelry or rhino horn jewelry; to people here in the US or in Japan who want an exotic pet that happens to have been poached from the wild; to people looking to traditional cures and remedies.

"Traditional Chinese medicine is alive and well in China and in Vietnam, and things like rhino horn are traditionally used to treat fever.

"A grandmother might keep a little bit on hand to treat her grandchildren when they get sick.

"Finally there's these newfangled uses for things like rhino horn. In Vietnam it is developed as something of a cancer cure and also something of a party drug - it's something you grind up after a night of heavy drinking and then you and your friends take a shot of it mixed with water and it's just this ultimate display of wealth and power."

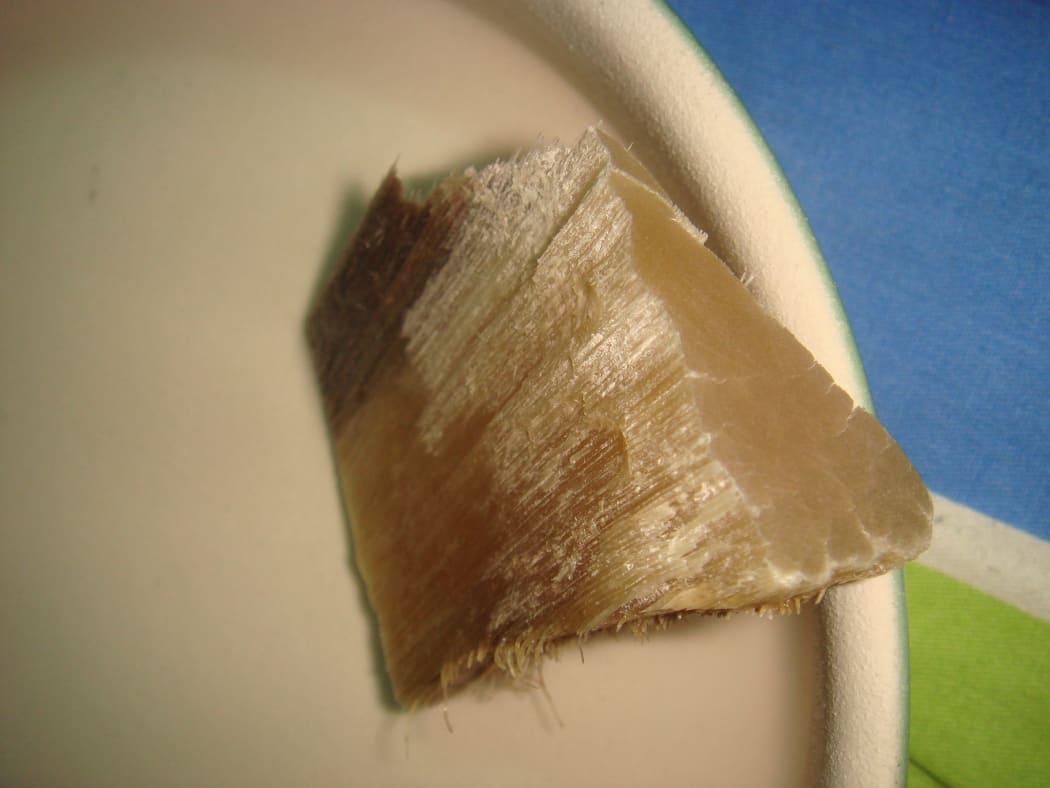

A rhinoceros' horn with a plate used to grind it to powder. Photo: Creative Commons / Thang Nguyen

She says she interviewed one of the people using rhino horn in that way.

"He was a wealthy businessman … we arranged to meet at a kind of trendy restaurant, we were surrounded by Vietnamese clientele, also foreigners, he brought his very young mistress along.

"At the beginning of the meal he handed me this tin box, an cookie tin, and oreo tin, and I thought 'oh great, now I have to eat all these oreos as a sign of thanks' but I open the tin and instead of cookies being inside there was a piece of rhino horn."

She says he was totally unafraid of any chance of getting caught.

"Midway through the meal he actually took the horn out and started grinding it up to show me how he uses it and he even offered me a shot.

"Keep in mind there's people all around, the waitress is coming over to our table but he just had no compunction about doing this because he knows there's zero chance of him getting caught or apprehended or in trouble.

"He also told me that he actually knows that the horn doesn't work as a hangover remedy, he just continues to do it because all of his friends do, so that all just illustrated to me how far we have to go to stop the trade.

"For some consumers the rarity is actually a plus, the rarer it is the more it shows how special and important and rich you are, for being able to buy one of the last ones - likewise for these animals being illegal."

Plight of the poacher

She says as long as there's this high demand for these product, poachers are going to continue the illegal trade - even though many may not like doing it.

"If there was no demand for these things no one would bother going into a park to risk their life to kill a rhino or an elephant," she says.

"Poachers are killed all the time attempting to poach and it's not fun business either, it's really difficult work."

Another person she met with in Vietnam was pangolin poacher, who welcomed her into his home for a meal cooked by his wife.

"His name was Tom Ho … he specialised in pangolins because they paid the most. He told me that the reason he began poaching was because his son was born with a brain defect."

Pangolins are thought to be the world's most trafficked mammal behind humans. Photo: Creative Commons / Flickr / Adam Tusk

"Tom Ho lives in a part of Vietnam where the average annual income is around $700 per year. He was an agriculturalist - a farmer. He had no money to pay for his child's hospital bills.

"He also blamed the Americans for his child's defects, he was in a part of Vietnam that was heavily bombed during the war.

"Tom Ho said he really hated poaching - he said 'you know, I go into the jungle at night, I come out and I'm covered in leeches and mosquito bites, I'm cut up from all the thorns. It's really horrible work but I'm gonna keep doing it because I want to help my kid and I want to feed my family."

She says she had gone into her project with a lot of preconceived ideas about poachers being evil, heartless individuals - but really struggled to condemn Tom for his choices and sympathised with others who would see no other options but following that path.

Curbing demand: A new science

She reiterates that solutions to poaching need to target reduction in demand - but doing so is a new science with little research, she says.

"We're going to have to target different users in different ways. For people like the wealthy rhino horn user I met, it's probably going to be figure out a way to convey to him that it is not cool to do this and also perhaps making him afraid that he could get in actual trouble for it.

"For some people - for example women who buy ivory in China there is some evidence that simply knowing about the plight of the animal can help."

For example, she says there was a big campaign run by the International fund for animal welfare

"It depicted a mother elephant walking with a baby elephant and the baby was so excited, saying 'mom I have teeth now' and the mother was not saying anything back because she knew that now her baby might be poached.

"This poster got so much positive feedback from women in China who said that 'I didn't even realise that elephants had to be killed for their ivory, I'm gonna never wear my ivory bracelets again'.

"For others, that might actually have the opposite effect and make users dig in their heels and say 'we don't care about these animals, we just want the rarity'."

The problem is also partly a cultural one.

"In China for example, animals are really seen as a commodity to be used for human productivity benefits."

Still, she says China has really ramped up its confiscations of illegal wildlife products coming across its borders, and the country's ban this year is probably the single greatest move for protecting elephants.

"China was the number one destination for poached ivory.

"So far the results of that ban in China have yet to reverberate into the field - poaching is still high and trafficking of ivory into China is still high, but at least you can't go into a store and buy a piece of ivory."

Controversial solutions

While bans can be somewhat effective, there are some conservation factions pushing for the opposite.

"There is a very strong contingency in conservation especially in Southern Africa of sustainable trade in wildlife products," Nuwer says.

"South Africa for example … we can credit South Africa with the return of rhinos."

She says South African officials had the wisdom to allow private individuals to own, breed and make profits off wildlife through for example tourism like trophy hunting.

"Many South African private rhino owners today would very much like to see international rhino trade reopened so they can sell their rhino horn to China, to Vietnam and use that money to protect their animals because poaching is at such an all time high right now.

"Certain nations - especially in southern Africa - would love to see the ivory trade reopened because they have stockpiles right now of all this material sitting there that they say could be auctioned off and used to pay for protections of animals in their countries."

Volunteers carry elephant tusks from storage containers to a burning site on April 22, 2016 for a historic destruction of illegal ivory and rhino-horn confiscated mostly from poachers in Nairobi's national park. Photo: AFP / TONY KARUMBA

She's not convinced that's going to work, however.

"Past examples … show us that it is impossible to prevent illegal trade of these materials leaking into the market.

"When you have a legal trade, it provides a smokescreen for illegal trade and thus an opportunity and encouragement for poaching."

Corruption, greed and resourcing

Indeed, the number one problem in policing bans - and the same problem a legal trade in animal parts would face - is corruption, she says.

"Much of the poaching is enabled by bribes, by corrupt officials, by corrupt rangers.

"Sometimes I think they get lucky but oftentimes officials at airports are paid to look a different way.

"The thing about wildlife trade is it's a really low risk high profit industry and these goods are often mixed into other channels of criminal trafficking so you might find rhino horn thrown in with arms; tiger bone thrown in with cocaine, that kind of thing.

"There was a recent bust in China for example of … an air security official who was working with traffickers in Guangzhou and he was just ensuring that everything they checked in their luggage was let through.

"In other cases however we're talking about huge quantities - tonnes and tonnes of materials, so ivory, pangolin scales - and those are usually going out on cargo containers on ships, or shipped by mail.

"While many traffickers try to conceal their goods, they're also working with corrupt officials who are helping them get through."

She says resources for those defending against poaching is another problem.

"Oftentimes rangers are just completely ill-equipped to do their jobs.

Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Kenya Photo: http://www.rachelnuwer.com/

"They don't even have good socks or gear for going into the field where poachers might be funded by wealthy bosses from the city who are giving them the latest equipment and weapons."

She says different management can help a lot, as in the example of Zakouma National Park in Chad, where poachers on horseback rode in from Sudan and reduced what had been one of the largest elephant herds in Central Africa to 450 - a loss of over 90 percent - between 2002 and 2010.

"Everyone wrote this park off as a lost cause 'the elephants are going to die there's nothing we can do about it', but then this non-profit group called African Parks come in.

"They take over management from governments, so they completely overhauled how the park was run: they weeded out corruption, they stayed during the rainy season when most of the poaching was taking place, and now not only has poaching been reduced to effectively zero, they're actually seeing new elephant births."

She says she also sees hope in grassroots movements in Vietnam that teach younger people to get excited about conservation.

However, she says she oscillates between mild hope and despair, and says if poaching is to really be stopped, it must be tackled on the same scale as other illegal trade - in arms, drugs and human trafficking.

"Wildlife trade really isn't seen as an equivalent crime as those other categories of crime, but to tackle it, it really needs to be.

"If we just cared about stopping this enough, if we all just decided okay this is something we're going to do, we would be able to do it."