Now-retired former Commissioner of Works Bob Norman built roads, dams, canals and viaducts for 40 years, and says the government again needs the kind of expert advice the Ministry once offered.

Preserved AB 778 hauling the Kingston Flyer Photo: CC BY 2.0

New Zealand's second-to-last such commissioner, Norman presided over the former Ministry of Works and Development for three years in the early '80s. He also worked on many projects as a civil engineer, including some of the Think Big projects of the 1970s.

"There is no longer a major agency serving government that is able to do this, but what we have got is a public, a very intelligent and critical public, and they've had enough and they want to sort this out," Norman says.

Norman says our once "world-leading" rail transport system is grossly under-utilised and our rural road network was never designed for heavy trucks.

He believes a fractured approach to transport has led to this over-reliance on roads over rail.

"We [MoW] designed and built a flexible rural pavement system. It was not ever designed for the sort of traffic that is being carried now. And right now of course it is just getting pounded to pieces - it can't keep up.

"Let's not kid ourselves that we have built a system that can manage the type of haulage that is going on."

Norman's career started just after WWII when the country was in dire need of repair.

"We came back after 18 months of service with the Army and there was New Zealand, and people don't realise that they had lost the services of 140,000 people who were on active service, and that was the dent in the intellectual capital that the country had been denied.

"So what we got back to was a whole lot of broken down farms and villages and gravel roads, and broken down bridges and over-crowded schools and hospitals, and the country had been denied that huge resource for six years."

The government at the time had a "get stuck in" approach, Norman says.

"So we did just that and so away we went and it was really great, halcyon years. We were busy putting in so much infrastructure and it really was a great ride."

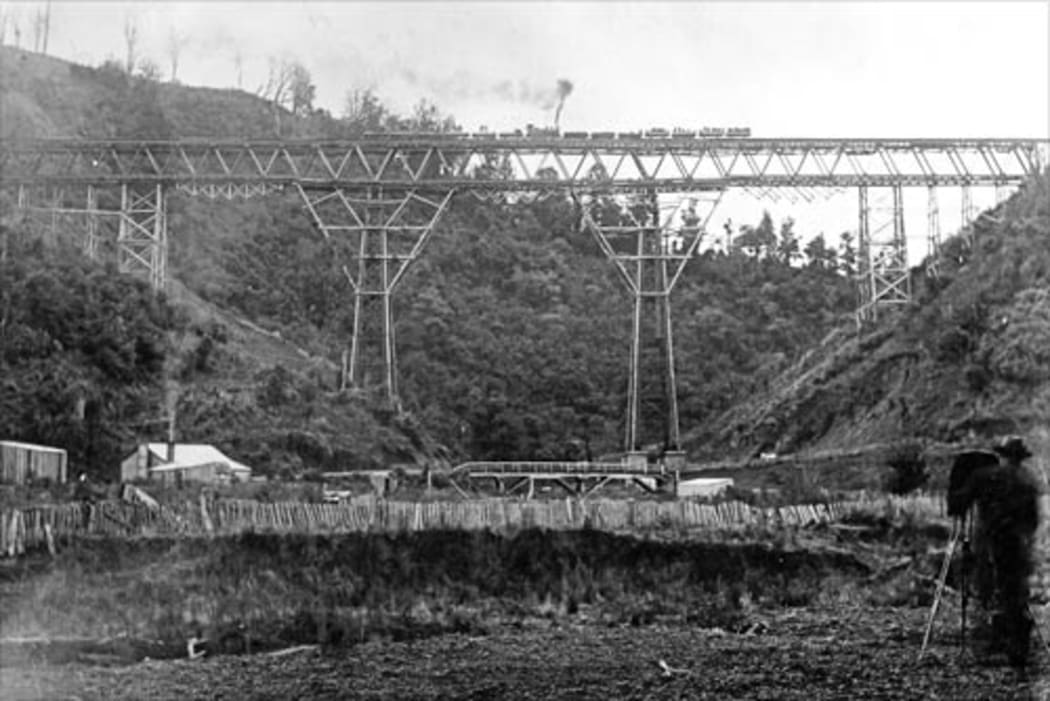

Building rail infrastructure dominated the early part of his career, he says.

Makōhine viaduct near Ōhingaiti between Hunterville and Mangaweka. Photo: CC BY 3.0 NZ

"New Zealand's railways opened up the entire country. Here we were - a hunk of rock sticking up 3000 metres into the trade wind belt - and a bundle of Kiwis came down from the UK and we built one of the world's finest rail systems.

"It was a narrow gauge system, which was quite appropriate for the terrain which we had to travel, and it was really quite an exercise. We had some of the world's highest viaducts, the Ōtira tunnel tunnel five and a quarter miles long was the longest railway tunnel in the world."

Having built the infrastructure, New Zealand made its own locomotives to run on the new narrow gauge tracks.

"Our engineers designed and built a steam engine called the AB - now, this AB steam engine led the world in steam engines for 50 years. It was the most efficient locomotive ever designed in terms of tonnes of draw bar pull per pound of steam.

Euclid R-15 dump truck. The backbone of the New Zealand Ministry of Works haul truck fleet on hydroelectric power projects from the 1940s into the mid 1970s Photo: contractormag.co.nz

"So we built these magnificent locomotives, these ABs and they did all the haulage for our railway system and so I was very lucky to be in just towards the end of that."

One of Norman's last rail projects was the final leg of the East Coast railway between Wairoa and Gisborne.

Roads then came to dominate the national transport agenda, he says.

Newmarket Viaduct Photo: Wikicommons

Big infrastructure projects often mean people are displaced, he says, and the construction of the Newmarket flyover in Auckland involved negotiating the purchase of a block of privately owned homes.

"It involved displacing a whole lot of people from houses and we negotiated the whole thing, except one, and the one property we could not buy - we could not negotiate - was owned by an old lady named Mrs Pearce - and she absolutely refused to move.

"And here we were, with a huge flyover in the centre of Auckland and the minister said - I think it was a marginal seat - 'no way are you going to move Mrs Pearce' and so we redesigned the bridge so the structure flew right over her property.

"It never disturbed her in any way, and finally in the general conditions of contract was a special clause which dealt with Mrs Pearce who was not to be disturbed.

"We went over at the end of the job and we congratulated ourselves, it was all done, we put in the last cables and poured the last concrete and then old Mrs Pearce died."

As Commissioner of Works towards the end of his career, Norman was asked to build the Ngauranga Interchange in Wellington.

Wellington urban motorway Photo: CC BY 2.0

"Well, we'd had a terrible experience 40 years earlier when we built the Petone level crossing ... a whole lot of scaffolding all over the Hutt Road, the queues of traffic were bumper-to-bumper from Ngauranga, from Thorndon to Lower Hutt and happened every day."

He knew from these past mistakes that a new approach was needed.

Ngauranga Gorge. Photo: Supplied/NZTA

"We found out that the Germans had developed a system called incremental launching and by this way you didn't have any scaffolding at all: you put the piers up but the roadway was left totally undisturbed and then you built all the bridge at one end and you pushed it over.

"They called it the toothpaste bridge."

This was a first in New Zealand, he says.

"The contractors would have nothing of it, they thought it was too much risk and so what we did, we bought the gear and we gave it free to the contractor.

"We also took all the risk for the problems that might arise because we were into innovative construction - what a success story that was."

Norman says the government lacks a top-level independent group of engineering advisors to advise it. A recent example is forestry where there is no oversight.

"Look what happened in Tologa Bay: there you've got a community brought to its knees on the East Coast by indiscriminate private forestry because there was no State Forest Service to regulate the way they got rid of the trash.

"Down came the trash and laid waste to all the riparian farmlands in the Tologa Bay area, it inundated houses and wrecked our roads and bridges along the East Coast."

Norman says New Zealand's early engineering pioneers left a remarkable legacy which should not be squandered.

"I'm not a socialist or a communist or whatever but we need the resources in central government.

"Our heritage should not be subject to market competition, it should be subject to cooperation.

"Things like transport should be run by a single authority which looks after roading and rail and makes the right decision on the disposition of those freight runs."

Playing Favourites with Bob Norman

Bob Norman QSO, is a former civil engineer and author of To Get to the Other Side: a Personal Encounter with Some Bridges Around the World. Audio