Hector’s work and encouragement to publish results marked the beginning of the growth of science in New Zealand. People stopped thinking that you had to send material overseas to have it described.

Simon Nathan, Hector's biographer

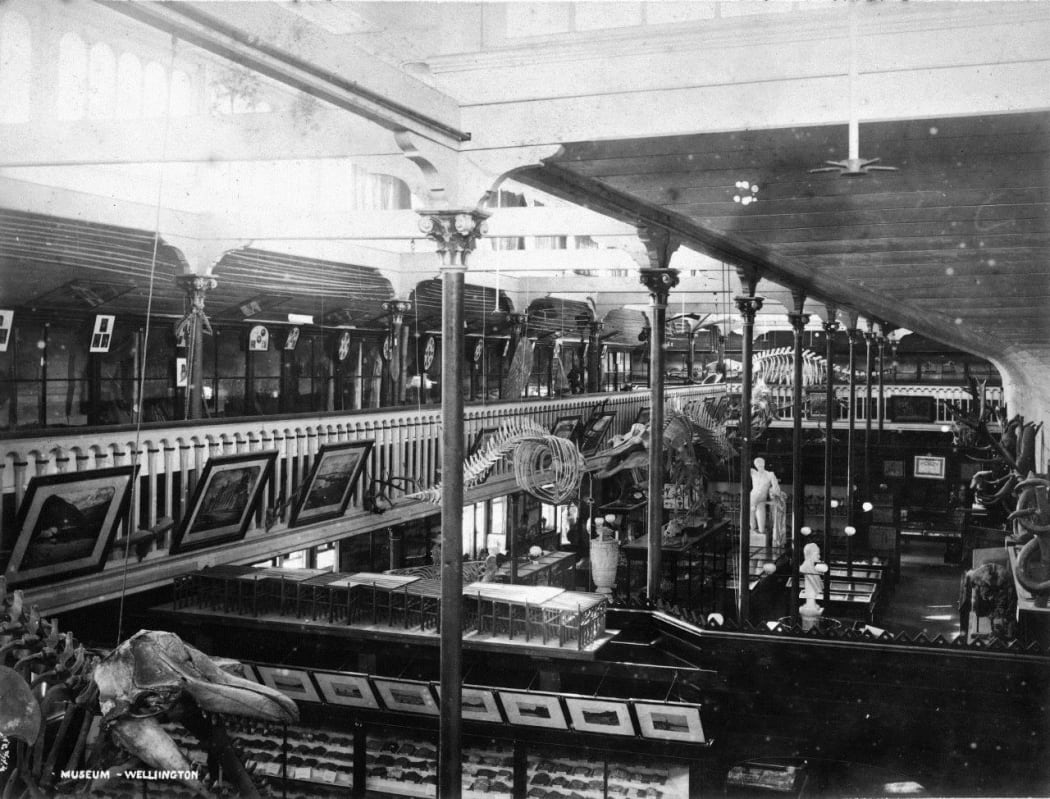

The interior of the Colonial Museum, founded by James Hector, seen here in 1880. Photo: Alexander Turnbull LIbrary

It’s 150 years since a young James Hector arrived in Wellington to take up his position as New Zealand's first government scientist. His legacy continues to this day, with several science institutions that can trace their beginnings to Hector’s insistence that New Zealand needed them.

The Colonial Museum he founded is now Te Papa Tongarewa, the Geological Survey he headed has since evolved into GNS Science and the New Zealand Institute has become the Royal Society of New Zealand.

We also have Hector to thank for the MetService, Wellington’s botanical gardens, and the fact that time is standardised across the country. His name lives on in more than 50 plants and animals, with Hector’s dolphins perhaps the best known example.

Simon Nathan, a geologist, science historian and biographer. Photo: Simon Nathan

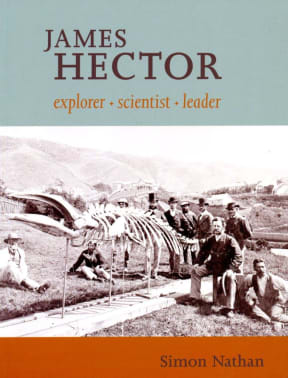

In his new biography – James Hector: Explorer, Scientist, Leader – science historian Simon Nathan charts Hector’s rise to becoming NewZealand's go-to person for anything to do with science.

Hector first came to New Zealand to carry out a geological survey of the Otago province, but after gold was discovered in Central Otago, he was appointed New Zealand’s first government scientist, tasked with the management of a nation-wide geological survey.

Hector’s own definition of his job was far broader than geology. During a year he spent in London he had been inspired by various learned societies and initiatives to start museums. When he was asked what he needed to carry out a geological survey of New Zealand, he asked for a museum to store any specimens he would find and for a laboratory to analyse mineral samples.

He thought of it as part of the job. He was exploring a new country and as well as looking at the rocks he should be looking at the plants and animals and he was very strong on weather recording.

Once several institutions were set up, Hector went through a “biological period”, collecting fossils, dispatching other naturalists across the country to collect plants and animals and focusing his own efforts on describing New Zealand’s whales and dolphins.

As it turned out, he was so busy with fieldwork that he couldn’t attend the opening of the Colonial Museum, leaving scientist-cum-politician Walter Mantell to design the layout of the collections and exhibits.

Mantell’s most notable association was with Richard Owen at the British Museum, whom he supplied with crates full of moa bones. Simon Nathan says Mantell was regarded as the moa expert in New Zealand, but in the end, it was Owen who gained fame and fortune from the reconstruction of the largest moa skeleton. This colonial relationship was typical of the time, with New Zealand scientists being seen as mere collectors.

"One of the reasons we can be grateful to Hector is that he was very keen that anything that was done under his direction should be published."

To this end, he founded the first scientific journal in New Zealand, the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, which he edited for 35 years.

Up to that point every specimen was usually sent to Britain for experts there to work on it. All plants and animals and fossils. Hector’s work and encouragement to publish results marked the beginning of the growth of science in New Zealand. People stopped thinking that you had to send material overseas to have it described.

You can also listen to Simon Nathan's interview with RNZ's Kim Hill, in which he explores Hector's relationship with Julius von Haast.

Hector had his fingers in many pies, but he was good at delegating. “He was fairly controlling, but also encouraging. He encouraged staff to write up scientific papers and he directed them as to where they should go. He told them what they should do but left the doing to them.”

He employed the same approach to the study of New Zealand’s natural history, appointing Walter Buller and Frederick Hutton to study birds and John Buchanan to describe plants. His own focus turned to cetaceans, New Zealand’s whales and dolphins.

Simon Nathan thinks that Hector wanted to use his medical training and his knowledge of anatomy and dissection techniques to make his own contribution. “He described a lot of [species] in a major paper on what was then known about whales and dolphins in New Zealand, and that’s where he first described Hector’s dolphin. The interesting thing for people studying the dolphins now is that it was much more widely spread when he described it than it is today.”

One of Hector’s lesser known contributions is the standardisation of time across New Zealand. Back then, time was determined astronomically and every town had its local astronomer. It was only in 1868, when the first Cook Strait cables were laid to allow for the transmission of telegrams that it became important that offices in different places had the same opening hours.

Photo: Simon Nathan

Always a diplomat, Hector suggested that the time at longitude 172’30’’, which runs through Christchurch, should be used as a national standard to avoid an argument between the new capital Wellington and Dunedin.

“Because of that New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to have a standard time.”

Simon Nathan says Hector would be gratified to know that many of the organisations he founded are still here today. “He would have had a little chuckle that he had the weight of responsibility for all those organisations on his shoulder.”

James Hector: Explorer, Scientist, Leader is published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand, and Simon Nathan will also speak at the History of Science conference at Victoria University next week.