"We humans have terraformed Earth, and what you see is an exponential increase in human effects on the planet … [happening] roundabout 1950.”

Colin Summerhayes, Emeritus Associate at the Scott Polar Research Institute & member of the Anthropocene Working Group

Geologists are debating whether to add a new epoch to the geological time scale, one that reflects the enormous impact that we humans have had on the planet’s physical, chemical and biological processes.

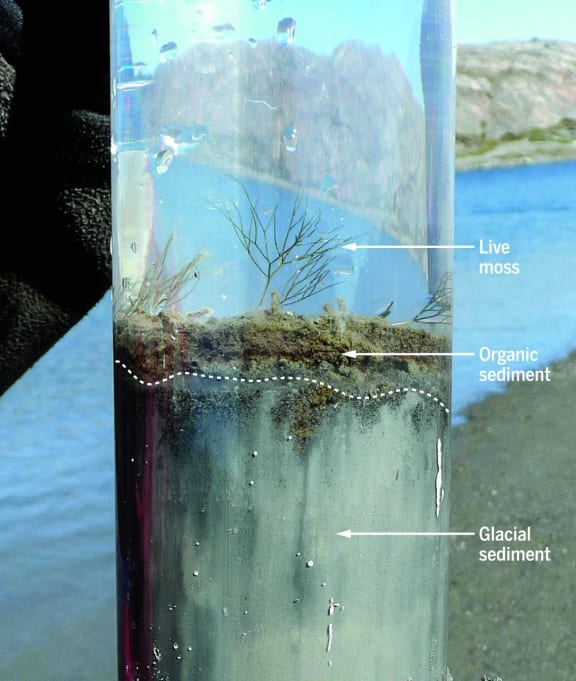

This sediment core from west Greenland shows an abrupt transition from glacial sediments to non-glacial material, as a result of climate warming causing glacier melt and retreat. The recent non-glacial material includes plastics, fly ash, radionuclides, metals, pesticides, and reactive nitrogen that are all a consequence of human activity. Photo: JP Briner

The new epoch would be known as the Anthropocene, and would see the end of the current epoch, the Holocene. Up for debate is the exact date that would mark the beginning of the new epoch, and the actual measure that would physically mark the boundary between the two periods.

The geological time scale is a way of measuring the Earth’s 4.6 billion year history in manageable – and meaningful - chunks. We are in the Holocene epoch, which dates back 11,700 years. The Holocene is a subdivision of the Quaternary period (which dates back 2.58 million years), which is itself part of the Cenzoic era, which falls under the Phanerozoic eon.

Geologically distinct boundaries mark the beginning and end of different parts of the time scale. The end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene epochs is the end of the last great ice age and the beginning of the current warm period.

Probably the most well-known boundary is that which marks the end of the Cretaceous period and the beginning of the Paleogene, 66 million years ago (it also happens to be the same boundary as the end of the Mesozoic era and the beginning of the Cenozoic era): this is the mass extinction event that saw the end of non-avian dinosaurs, most likely caused by a large asteroid impact.

As the title of a recent paper in Science put it the Anthropocene has to be ‘functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene’, and this is what the Anthropocene Working Group is currently debating. The working group is a committee of the International Commission for Stratigraphy, which in turn is the largest and oldest constituent scientific body in the International Union of Geological Science, and it is responsible for deckiding on the geological time scale.

New Zealand-born scientist Colin Summerhayes is Emeritus Associate at the Scott Polar Research Institute and is currently Erskine Fellow at the University of Canterbury. He is one of the members of the Working Group, and says “the evidence we now see is strong enough for us to put a boundary in.”

“Our feeling is [the boundary of the Anthropocene] should be around 1950, and the reason for that is that this is when the exponential curve of human activity really rises, and what we can see is that increases in the production of materials, such as plastics, brick and concrete went through a massive upswing at the end of World War Two.”

A decision will be made by the International Commission for Stratigraphy, which meets in South Africa in September.

Last year on Our Changing World, Veronika Meduna interviewed award-winning science journalist Gaia Vince about her book 'Adventures in the Anthropocene."

A story about the Great Acceleration and the recent Science paper featured on RNZ earlier this month.

In early 2015 an international team of scientists warned that we had crossed four out of nine major planetary boundaries.