"The sperm is on a race to get to the egg, and I'm on a race to get the sperm under microscope." Helen Taylor, University of Otago

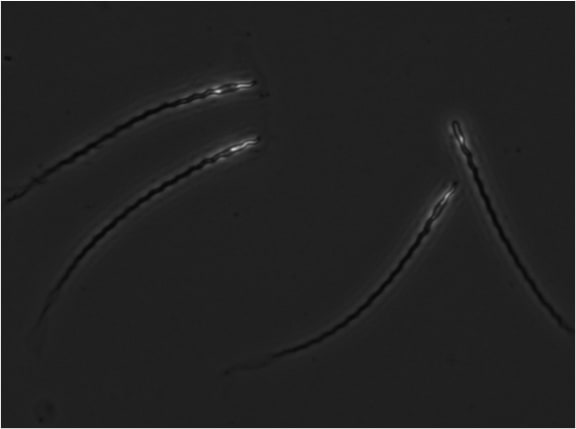

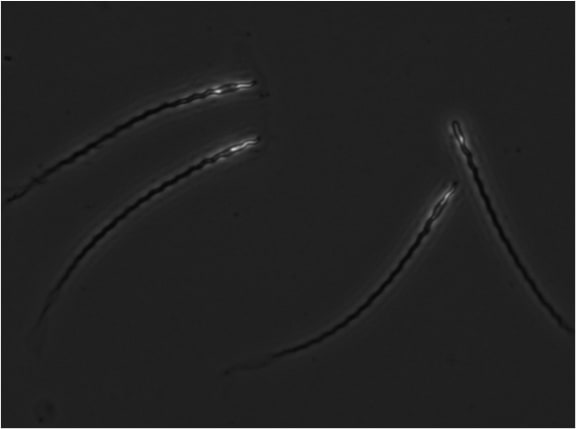

Dunnock sperm, seen under a microscope. Photo: Helen Taylor / University of Otago

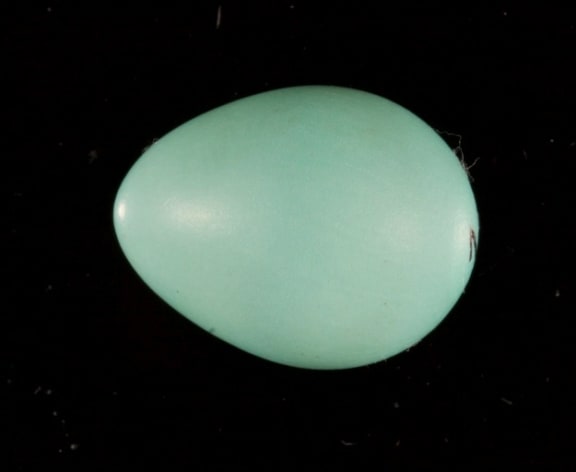

This year's bumper kakapo breeding season has highlighted a significant problem in the conservation of rare species - nearly half of the more-than-120 kakapo eggs that have been laid are infertile, and a significant number of fertile eggs are dying before they hatch.

Scientists suspect much of the problem lies with the male birds, which may be 'shooting blanks' or have poor quality sperm.

The problem is not unique to the endangered kakapo, and University of Otago post-doctoral researcher Helen Taylor has spent the last year on a bird sperm-collecting tour of the country to see if she can get some clues to what is going on.

Population bottlenecks

The birds that are part of her study include natives such as South Island robins and hihi, or stitchbirds, as well as familiar introduced blackbirds and dunnocks, or hedge sparrows.

New island populations of native birds often experience a genetic bottleneck because only a small number of birds are translocated. For example, just five robins were taken from Kaikoura to establish a new population on Allports Island.

A dunnock that has just been caught in a mist net. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

In the case of dunnocks and blackbirds, only a few birds survived the long boat journey from England in the 1800s, when naturalisation societies were populating New Zealand with familiar English birds. All the dunnocks alive in New Zealand today, for example, are descendants of just 200 birds.

All these species have gone through a severe population bottleneck, when only a few individuals survived, and as a result there is not much genetic diversity and a high incidence of inbreeding (close relatives mating with one another).

"Inbreeding seems to have a universal effect on male fertility, and it's not clear why," says Helen. "This hasn't been studied this much in birds, either, and by looking across a variety of birds we are trying to see if there is a common mechanism that makes males susceptible to inbreeding depression … we're looking for genes that might be affected, so genes for spermatogenesis or sperm manufacture."

Helen says many of our native birds are threatened and in low numbers, and that trying to boost reproductive success is very important.

"If we're seeing birds with quite high incidences of hatching failure we need to know why that is. Is it problems with embryo development or is it issues to do with male fertility, so that we can try and manage for that in the future," says Helen.

What sperm can tell us

Helen Taylor massages the cloaca of a dunnock, and a tiny glass capillary tube will collect any semen produced. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Helen collects semen from birds using cloacal massage, and says that even a tiny amount of semen can contain millions of sperm.

"It's pretty cool. You can see [the sperm] swimming, and these ones are swimming pretty fast," comments Helen as she looks at a sample of magnified dunnock sperm.

"What I'm working on is concerned with male fertility in birds, and in particular with sperm quality, so sperm motility, sperm morphology and DNA fragmentation within sperm, and how that might be related to genetic diversity and inbreeding in species that have experienced population bottlenecks."

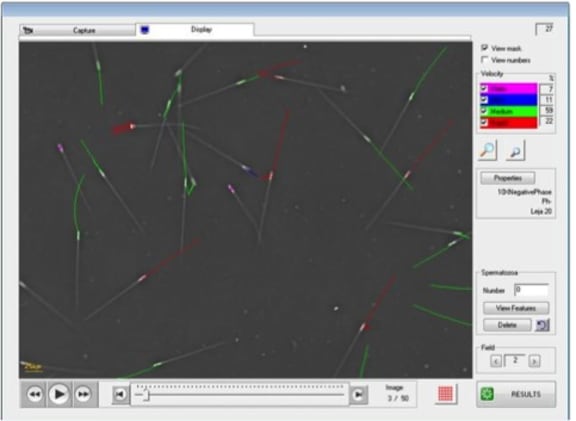

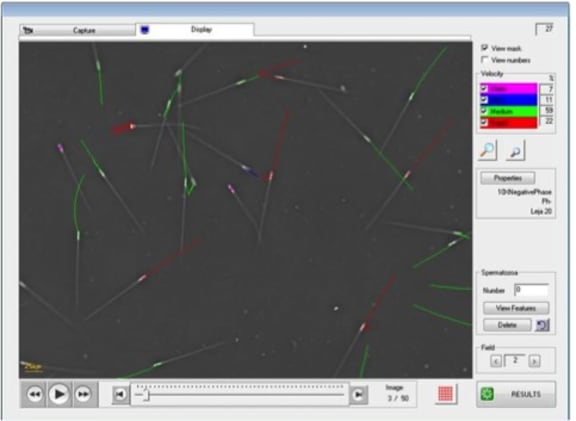

A computer-assisted sperm analysis system connected to a microscope automatically videos and tracks the sperm, and collects information on how fast each sperm is swimming and whether it is swimming in a straight line or in circles (the motility, or movement).

A computer-assisted sperm analysis system connected to a microscope automatically videos and tracks the sperm, and collects information on the direction and speed of each sperm. Photo: Helen Taylor / University of Otago

"If they're swimming round and round in circles then obviously that's not going to get them anywhere. Bird sperm tends to swim quite straight, so if we're seeing sperm that's got a very smooth, straight trajectory then that's a really good sperm that's going to make good headway in the female's reproductive tract."

Helen says she has been very impressed by the variation in sperm she has looked at.

"The sperm of the different birds are so different. Some are longer than others, some are short and fat, and some of them swim in a certain way."

"We're looking for differences in sperm quality between males, and trying to figure out what's causing it," says Helen. "Is it to do with their age? Is it to do with inbreeding and genetic diversity - that's what I'm most interested in … or with their social status?"

Inbreeding is reduced genetic diversity caused by mating between close relatives, and it may affect reproductive success. A recent study with gazelles showed that inbreeding results in sperm with high levels of DNA fragmentation, or damage. Sperm with high DNA fragmentation swim more slowly, have more abnormalities, and if they manage to fertilise an egg there is a higher rate of death in the offspring. In humans, DNA fragmentation causes higher rates of miscarriage.

No one has looked at these issues in birds before, and Helen says "we want to see if there is damage at a fundamental level, is inbreeding depression affecting the DNA that is being carried by the sperm cells? Because that could have implications for fertility, embryo development and a wide range of traits that could cause problem with reproduction."

The interesting sex life of the dunnocks of Dunedin Botanic Gardens

A dunnock or hedge sparrow. The coloured bands on its legs give it a unique identification. Photo: Carlos Esteban Lara / University of Otago

Dunnocks, or hedge sparrows, are - at first glance - unremarkable small brown birds that look like house sparrows. But they are actually a type of bird know as an accentor, and are not closely related to house sparrows.

There is a thriving population of dunnocks in the Dunedin Botanic Gardens, and they are well known birds, having been studied intensively by a succession of students from the Department of Zoology.

Carlos Esteban Lara is the latest PhD student, and he is studying the mating systems of the dunnock, which - for a small drab bird - turns out to have an interesting sex life.

Dunedin's dunnocks have two different approaches to making and raising babies.

Some birds practise monogamy, but others practise polyandry, in which several males mate with a female and then both help her raise her chicks.

Carlos says this is a great system for a female - by having several helpers she can raise more chicks. But he says from a male perspective it is not such a good deal, as each male fathers fewer chicks than he would if he had a monogamous mate.

"Because there are many males mating with the same female it creates sperm competition, because they need to produce better sperm to guarantee paternity," says Carlos.

Helen Taylor is collaborating with Carlos in the collection and analysis of sperm from the Dunedin Boatnic Gardens' dunnocks, and the benefit for both of them is that they are collecting sperm from dunnocks with a known history. Carlos knows exactly who is related to who, which birds are the dominant alpha males and which the lower ranked beta males, as well as other personality traits such as which birds are bold and which are shy.

Ultimately Helen's hope is that those tiny samples of sperm may hold the answer to many questions related to biology and conservation. Hopefully, it will help solve problems such as the low fertility dogging endangered species like the kakapo. It might also shed light on human fertility as well.

Want to know more?

During the 2009 kakapo breeding season Our Changing World featured several stories on sperm collection from kakapo, artificial insemination and the creation of a kakapo sperm bank.

Sheri Johnson talked with us about her research on zebrafish sperm and aging fathers.

Helen Taylor appeared on Our Changing World during her PhD research into the genetics of little spotted kiwi populations at Zealandia sanctuary and elsewhere.

And Helen and Sheri also updated their work and shared their results.