Weather. It’s not just something that happens here on earth. Space has weather, too, including solar storms and winds that can, at times, ramp up to tsunami force.

And these solar tsunamis have the power to disrupt to our modern technology-based lives, which have become very dependent on electricity and satellites.

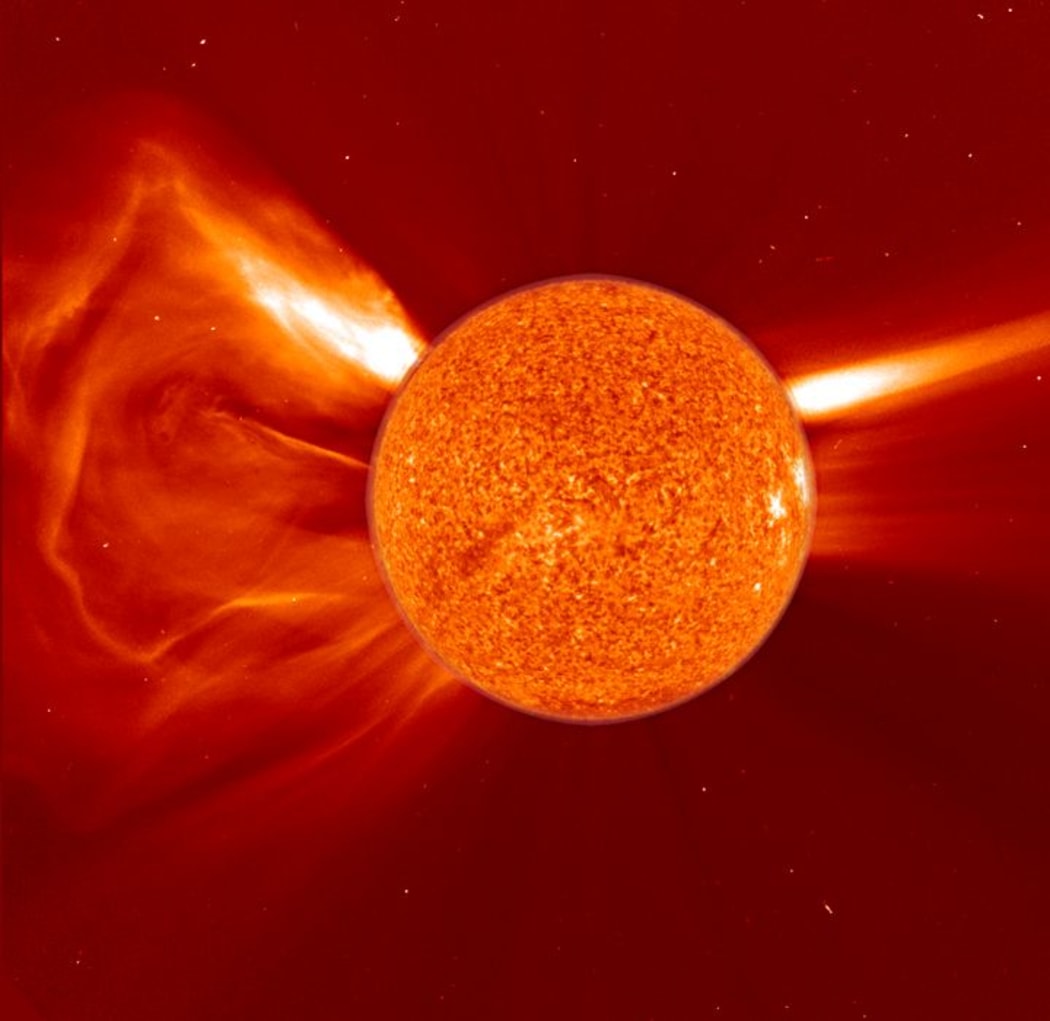

A coronal mass ejection from the Sun has the power to create a powerful geomagnetic storm that could disrupt power supplies on earth. Photo: NASA

Space physicist Craig Rodger at the University of Otago is working with Malcolm Ingham, at Victoria University of Wellington, using data from Transpower, to calculate the risk to the New Zealand electricity network from extremely large geomagnetic storms.

Craig Rodger says that New Zealand has already experienced the consequences of one such major storm when, in 2001, an electricity transformer in Dunedin was destroyed and a second one taken offline. Fortunately there was enough redundancy built into the system to ensure the national power grid continued functioning.

The Sun and space weather

“The surface of the sun is so unbelievably hot that it boils off into space”, says Craig. “There is this gentle breeze coming from the surface of the sun, blowing out in all directions into space. And when it gets to earth, if it’s in this usual gentle state it wafts past us at 300-400 kilometres per second.”

Craig says this solar wind is charged and carries with it the magnetic field of the sun. When it gets to earth it interacts with our magnetic field which effectively shields us. “[The solar wind] flows around the earth like water around a rock in a stream.” The only place that the solar wind can get around the magnetic field is at the poles, where it is visible as the aurora.

Aurora Australis (the southern aurora) photographed from the International Space Station Photo: ISS Expedition 23 crew NASA

What interests Craig, though, is when the usually gentle solar wind ramps up to become a solar tsunami. He explains that the sun is a gigantic spinning ball of burning gas, which spins at slightly different rates at the Equator compared to the Poles.

He uses the analogy of a rubber band to describe how, as a consequence, the Sun’s magnetic fields become twisted. Eventually the tightening ‘rubber band’ must reorganise its energy and it becomes a catapult, “literally taking a chunk of the sun and throwing it out into space. That’s called a coronal mass ejection – millions of tonnes of material being blasted out into space.” Coronal mass ejections can fire in any direction but occasionally one heads directly at earth.

The risk of a geomagnetic storm to national electricity grids

“Now, if [a coronal mass ejection] hits, you’ve a million tonnes of plasma crashing into the earth’s magnetic field, which will largely protect us but will get shrunk,” says Craig. “And that changing magnetic field sets up currents. [The risk is that] a long electric power line will end up having a current induced in it, and that’s a current that’s not expected to be there.”

The classic example is a major solar storm in 1989 that generated large changes in the earth’s magnetic field. These resulted in Quebec’s hydroelectric stations falling out of the Canadian power grid, resulting in the loss of power – in the middle of a very cold winter – to many households for a number of days. That incident prompted governments to begin investigating possible consequences.

The US National Academy of Sciences, for example, has warned that extreme geomagnetic storms could produce widespread power blackouts with permanent damage to more than 10 per cent of the primary transformers in the United States.

A similar analysis undertaken in the UK resulted in severe magnetic storms being added to their National Risk Register, although their findings suggested they could manage the consequences.

Craig says the magnetic risk to New Zealand from a severe geomagnetic storm is more similar to the risk in the UK than in the US. This is because we are closer to the Poles, but also because we are an island nation surrounded by water.

“Knowing what the risk is requires you to know the nature of the ground, the nature of the sea around the ground and the specific set-up of the electrical network.”

In space, satellites are also vulnerable to large geomagnetic storms.

In 2015, Craig Rodger and Malcolm Ingham’s project ‘Solar Tsunamis: Mitigating Emerging Risks to New Zealand's Electrical Network’ was awarded nearly $1.5 million over 3 years from the Hazards & Infrastructure Research fund administered by the Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment to work with Transpower to calculate the risk to the New Zealand electricity grid from a solar tsunami.

Craig Rodger spoke with Kathryn Ryan on Nine to Noon about the solar tsunami project.

He has previously featured on Our Changing World talking about space physics in Antarctica.

To find out more about the sun sounds, recorded by NASA’s SOHO spacecraft, that feature at the beginning of the audio story, check out Stanford University’s solar centre website and their feature on the singing sun.