The rich seas and sanctuary islands of Hauraki Gulf are home to millions of seabirds, including iconic Buller’s shearwaters

Buller’s shearwaters are a familiar sight out on the water, but not a lot is known about these medium-sized seabirds, that breed only on the Poor Knights Islands.

The Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust is determined to find out more.

Buller's shearwaters sitting on the forest floor, sketched by Abby McBride Photo: Abby McBride

Subscribe to Our Changing World for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts

Bellbirds are the cheerleaders of the day shift at the Poor Knights Island. Their chimes and gargles ebb and flow above the quiet ‘chip chip chip’ of a family of small, dark spotless crakes, rustling through the sparse leaf litter on the forest floor. Kohekohe and pohutukawa trees form a tall canopy, casting dappled light in which a tuatara basks, wary and ready to dash for safety into a nearby burrow.

Forest floor on the Poor Knights Islands honeycombed with Buller's shearwater burrows. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

The tuatara bolthole is one of many burrows that dot the bare forest floor, and most are home not to tuarata, but to fluffy grey Buller’s shearwater chicks. During the day, the chicks are home alone, but as night falls over the islands, and the bellbirds hush, there is a changing of the bird guard.

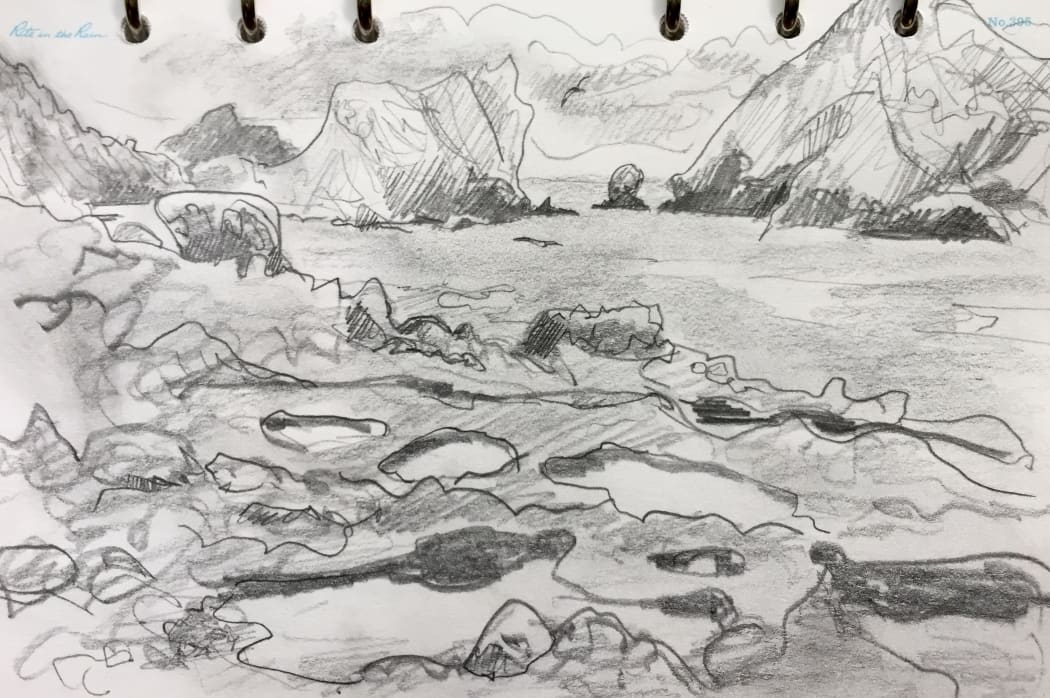

View across tidal pools on Aorangi Island's east coast, towards the Tawhiti Rahi, as sketched by Abby McBride. Photo: Abby McBride

The shearwaters return

Sit on the shore of Aorangi Island at dusk, looking towards the sea, and you will see dark grey shapes winging towards the island, and hear quiet whooshes as they shoot overhead. These are adult Buller’s shearwaters, returning from a day’s feeding in the rich waters of the Hauraki Gulf.

With almost reckless daring they crash through the forest canopy and within seconds they have oriented themselves on the forest floor and are scuttling to a nearby burrow. It’s a tight fit but the shearwater parent doesn’t hesitate as it slips easily into the cool dark burrow, to be greeted by a volley of eager high-pitched calls from a waiting chick.

Across the two large islands of Aorangi (110 hectares) and Tawhiti Rahi (163 hectares), this scene repeats as numerous birds crash-land like kamikaze pilots. Exactly how many thousands – or tens of thousands of birds – is a question that the Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust is trying to answer, with funding from Birds New Zealand’s research fund.

Buller's shearwater. Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Marcel Holyoak

Hauraki Gulf – seabird hotspot

Seabird expert Karen Baird with a Buller's shearwater chick. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

The Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust is a small organisation, determined to draw attention to – and find out more about – the seabird riches of the Hauraki Gulf.

Trustee Karen Baird is seabird advocate for Forest and Bird, and for Birdlife International. “Seabirds are cool,” she says, “because they make their living at sea for most of their lives, and then they’re still able to be incredibly capable on land. Not many people would realise a seabird can climb a vertical rock - and it can also catch its food at sea.”

Fellow trustee James Ross says that “because of where they feed, [seabirds] are subject to large processes such as climate change and the effects of fishing.”

Ross says that the Hauraki Gulf is a seabird hotspot, home to 25 breeding species, including five that breed only there. New Zealand storm petrel, the Hauraki Gulf little shearwater, Cook’s petrel, black petrel – and Buller’s shearwaters, which breed only on the Poor Knights Islands.

Bush-covered cliffs on Aorangi Island, sketched by Abby McBride. Photo: Abby McBride

The Poor Knights are a marine reserve and world-renowned diving destination, known for their subtropical waters and wildlife, the stingrays that glide through underwater arches and swirling schools of pink and blue maomao.

Most people are unaware that the cliff-girt islands they dive around are just as rich in life above the waterline. The islands are strictly protected nature reserves, and few people are allowed ashore. There is a good reason for this – honeycombed with Buller’s shearwater and other seabird burrows, the forest floor is extremely fragile.

View across Aorangi Island to Tawhiti Rahi, in the Poor Knights group. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

A home for Māori

These islands have always been free from rats and stoats, but they are far from pristine. Both islands were occupied by Māori for hundreds of years, and there is ample evidence of their presence: pa sites, garden walls, stone adzes and flakes of obsidian.

Ancient pollen from a soil core taken on Tawhiti Rahi has revealed that the prehuman forest was a unique conifer-and palm-rich forest. That forest is long extinct, replaced by pohutukawa and kohekohe, but many large reptiles, weta and centipedes survived the changes and roam the island each night.

Abby McBride's sketch of a Buller's shearwater about to take off. Photo: Abby McBride

Māori brought pigs to the island, and when settlement was abandoned in the 1820s the pigs remained on Aorangi, churning the ground, and uprooting and eating Buller’s shearwater eggs and chicks. While the shearwaters were abundant on Tawhiti Rahi, only a small number were nesting on Aorangi in the 1930s, when pigs were finally eradicated.

The birds wasted no time in recolonising, but although earlier estimates suggested there may be 200,000 or so breeding pairs on Aorangi alone, James Ross and seabird expert Karen Baird suspect the real number is much lower than that.

Seabird biologists with their arms in seabird burrows checking to see if there are any Buller's shearwater chicks at home. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Counting seabirds

The Northern New Zealand Seabird Trust is using a number of methods to count Buller’s shearwaters on Aorangi. Sound recorders are creating a noise index across the island, which will be correlated with the density of burrows in different habitats. And there are regular checks of some permanent transect lines that Graeme Taylor, from the Department of Conservation, set up in 2011.

Every burrow within five metres of the 30m-long transect line is checked – this involves someone lying on their stomach and carefully inserting an arm as far as they can reach. If there is a chick within reach it is carefully extracted, then weighed, measured and banded with a unique numbered metal ring, and returned to the burrow.

Young Buller's shearwater chick. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

The numbers of occupied burrows can be compared to previous years, to find out if the Buller’s shearwater population is going up or down.

A similar survey on larger Tawhiti Rahi in 2017 concluded there are 137,000 breeding pairs of Buller’s shearwaters on that island, and James Ross says that including all the non-breeding birds takes the population estimate for that island to about half a million birds. They expect to find fewer birds on smaller Aorangi Island.

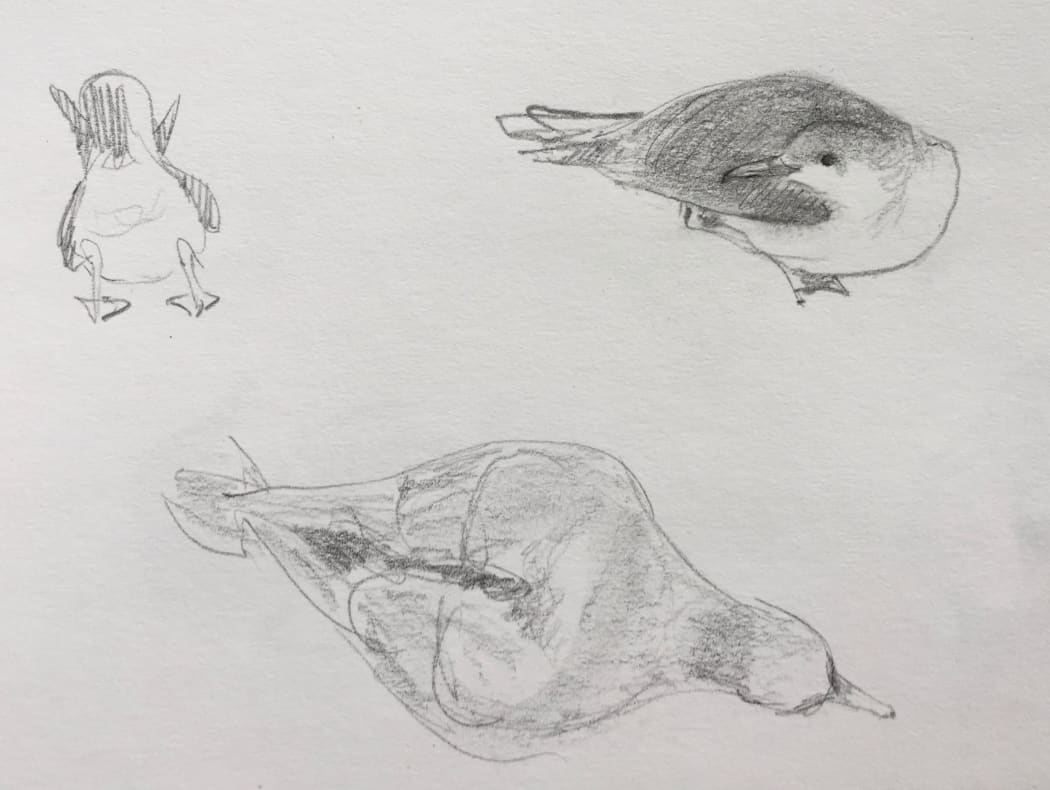

Sketches of Buller's shearwaters on the forest floor, by Abby McBride Photo: Abby McBride

Abby McBride sketching at the Poor Knights Islands. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

Sketching seabirds

Abby McBride calls herself a sketch biologist, a term she coined to describe her work at the intersection of field biology and art. She is spending nine months in New Zealand as a Fulbright-National Geographic story-telling fellow.

She is visiting as many seabird projects as she can,”because New Zealand’s seabirds are the most diverse and endangered in the world.” She is particularly interested in the many seabird conservation projects that are underway.

Her tools of trade are a waterproof sketch paper and a pencil. Whenever she has a moment, she draws what she can see – a Buller’s shearwater sitting on the forest floor, the entrance of a burrow, a cliff towering above the shore..

Abby says her drawings are often quick impressions, capturing the essence of the bird and “the process that it’s in. Looking at the sketch as a viewer you get a sense of what it’s like to be looking at the bird.”

End of the night shift

Towards dawn on a late summer morning, there is a deafening chorus of howling and other-worldly whooping, as pairs of Buller’s shearwaters profess their undying love for one another and their annoyance at their noisy neighbours.

Most of the birds are now out and about above ground, slowly making their way to their favourite take-off points. If there is no nearby cliff to launch from, the birds will deftly climb a prominent tree or rock outcrop. These bear deep scratches from generations of claws and beaks.

A Buller's shearwater uses its tail and wings as it climbs a vertical rock to reach a take-off point in the forest on Aorangi Island. Photo: Abby McBride

Just before dawn, the noise and take-off activity crescendos and then a sudden silence falls across the islands. A minute or two later the first bellbird call breaks the quiet. The seabird night shift is over, and in burrows across Aorangi shearwater chicks with bellies full of small fish and plankton settle down to sleep.

Buller's shearwaters photographed off the coast of California. Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Tom Benson

Pacific travellers

During the breeding season, Buller’s shearwaters travel widely around New Zealand, feeding as far south as the Chatham Rise and out in the Tasman Sea.

At the end of the breeding season the birds begin a huge figure-of-eight loop that will take them around the Pacific Ocean, eventually returning to the Hauraki Gulf for the next breeding season.

Graeme Taylor from DOC says small geolocators attached to birds reveal that they fly first to the central Pacific where they feed for a couple of weeks. Once they have refuelled they head to the Emperor seamounts, north of the Hawaiian island chain.

From there they fly east to the coast of North America, where they feed at the edge of the California Current.

Finally, they return to New Zealand, their south-bound flight across the Equator intersecting their northward route.

Buller's shearwater at night, sitting near its burrow in a large rock pile. Photo: RNZ / Alison Ballance

More tales from seabird islands

Black petrels breed only on Hauturu / Little Barrier Island and Aotea / Great Barrier Island in the Hauraki Gulf. They are New Zealand’s most threatened seabird.

New Zealand storm petrels were dramatically rediscovered and eventually tracked to their breeding ground on Hauturu / Little Barrier Island.

Putauhinu is one of the southern titi islands, and is home to rare birds as well as sooty shearwaters.

A small population of fairy prions survives on predator-free cliffs near Dunedin.