A series of projects and creative conversations have been taking place at Victoria University via Wai-te Ata Press and The New Zealand Centre for Literary Translation, in conjunction with the Canadian High Commission.

Director of Wai-te-Ata Press Dr Sydney Shep, says that Entrenchments 2015 is a project that has allowed them to take the concept of a military trench and turn it upside down, examining what it mean to have entrenched ideas about war, what it mean to have a narrative that should be contested, and to look closely at how art mediates between the worlds of politics and culture. “Using technology today, we can broaden out the scope of the conversation," she says.

Taking interdisciplinary artists, some of the elements of the project include reinterpretations of written texts such as Patricia Grace’s novel Tu, which traces the experience of a young man who joins the Maori Battalion.

Taking interdisciplinary artists, some of the elements of the project include reinterpretations of written texts such as Patricia Grace’s novel Tu, which traces the experience of a young man who joins the Maori Battalion.

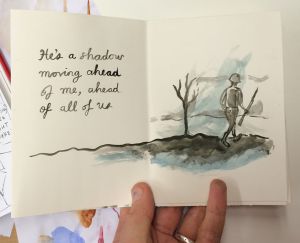

Sarah Laing, a Wellington-based creative writer and graphic designer has been enlisted to illustrate aspects of the book. She has chosen fragments of Grace’s text and is producing a series of miniature zines, comics and posters which she has begun illustrating in water colour and pen. Working with a short turn around adds to the challenge, along with the prospect of Patricia Grace herself, attending an exhibition where Sarah’s work will be presented on April 28th.

“Patricia Grace is a hero of mine [her] writing is beautiful and there are so many poignant moments, and so many moments that lend themselves to illustrative responses.”

Marco Sonzogni has been working intensively on the project. As a Literary translation scholar, he says that he uses any opportunity to bring words into contact with other realities and Entrenchments 2015 has been one of his most satisfying projects to-date and he puts that down to the creative conversations that have generated as a result.

“Incidentally I’m not so keen on commemorating war events. I respect what has happened and I feel for the families of those who have lost their lives and possibly given us a better world. But until we change the way we think and the way we look things, and until we engage on a daily basis on peaceful conversations, there is always going to be war.”

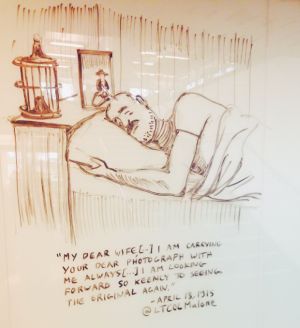

A highlight for Marco, has been the discovery of Canadian comic artist Julian Peters, who takes classical poems and illustrates and reinterprets them visually, into comic form. Invited to participate in Entrenchments 2015, Julian has been creating daily illustrations in response to daily text messages sent via the WW100 project.

Q & A with Julian Peters

How long have you been working as a comic illustrator?

How long have you been working as a comic illustrator?

As a kid I drew tons of comics, but I stopped as teenager, and started up again more seriously about ten years ago.

What attracted you to the idea of using poetry and interpreting this in a visual medium?

My return to comics was prompted by my idea to create a biography of Arthur Rimbaud in graphic novel form. The inspiration came from some drawings of the enfant terrible of French poetry done by his companion Paul Verlaine that I thought made him look a little like a dishevelled, bohemian version of Tin Tin. Although I unfortunately never finished this project, it had the effect of pairing poetry and comics in my mind, and got me thinking of other ways in which the two art forms could be combined.

Poetry is often thought of as the highest expression of language, the form in which words are pushed to the limits of their communicative potential. Comics too, is a language of a kind, with a full arsenal of its own particular expressive techniques, and it is an endlessly inspiring challenge to try to translate the power of poetry into visual form through the creative deployment of these techniques.

How would you describe your visual aesthetic?

I try to adapt my style somewhat to the poetic material at hand, but I’m always striving for a certain gracefulness of line, and the avoidance of visual clichés. I spent part of my formative comics reading years as a child in Italy, and most of my biggest influences as a comics artist still come from Italian comics.

What appealed to you about the Entrenchments project?

I think the First World War was such a traumatic and incomprehensibly insane experience for the societies that lived through it that it became very difficult to speak of it outside of a very narrow and rigidly codified set of rhetorical tropes –honour, sacrifice, sunsets, etc. The same is true of the visual rhetoric commemorating the war as seen in the monuments to the fallen, Remembrance Day ceremonies, and so on. The creation of new visual accompaniments to WWI-related texts provides an opportunity to subvert both the literary and artistic clichés through which the war is generally presented to us, and which, partly just through their very familiarity, can blind us to the true horror of the experiences they ostensibly serve to commemorate.

Lastly… is this concept of interpreting poetry into comic form a genre in itself?

The person generally credited with inventing poetry comics is the American writer and artist Dave Morice, who created some humorous visual renderings of a great number of classic poems beginning in the late seventies. I didn’t really know of anyone else who was creating poetry comics when I began to do my own about seven or eight years ago, but in the last few years the genre has really taken off, and there’s all kinds of really interesting stuff coming out every day, it seems.