Before women gained the right to vote and Māori seats appeared in Parliament there were the goldfield electorates. We ain't saying that they're gold diggers, but Jamie Tahana is and he explores why gold miners were given the right to vote.

Photo: 123rf

It took less than 20 years for a rabble of miners to change New Zealand dramatically.

They transformed landscapes. They moved mountains and built towns, and they brought a massive influx of migrants (New Zealand’s population more than doubled in the 1860s).

These people, mostly young men, arrived hoping to strike a fortune. Many more arrived to make a fortune off of them.

But one of the gold rush’s more quirky legacies is the effect it had on parliament and democracy. It slightly opened the door to universal suffrage, and set a precedent for the formation of the Māori seats, even if intentions were far from noble.

Many of the miners were rough, nomadic men who had followed the yellow nugget road from Australia and the United States.

They first went to Coromandel and Golden Bay for brief rushes in the 1850s, then the big rush came after Gabriel Read struck gold in Otago in 1861, sparking the infamous southern influx.

In only a few years, the province’s population went from a few hundred settlers to 24,000 in 1863.

Water races were channels cut across a hillside bringing water from streams to places where gold was mined. This water race in Central Otago was cut into the hill in 1877 to provide water for goldmine sluicing. Photo: ( RNZ / Ian Telfer )

Neill Atkinson, the chief historian at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage and the author of the book Adventures in Democracy, said New Zealand’s parliamentarians had spent years planning how to deal with a gold rush.

They had keenly watched what had unfolded in the Australian state of Victoria, particularly with the Eureka Rebellion of 1854.

There, miners in the town of Ballarat had revolted against the colonial administration, which was charging them tax while refusing to grant them representation. Twenty-seven miners were killed in the subsequent clashes.

“Everyone knew that gold rushes could be this disruptive phenomenon,” Atkinson said. “Gold rushes were inherently unstable. They involved huge and really rapid population shifts, mostly of relatively young men.”

“There was a clear concern in New Zealand -- and it’s discussed in parliament in the 1850s, well before the Otago gold rush - about what do you do about gold miners?”

Historian Neill Atkinson. Photo: Supplied / Ministry for Culture and Heritage

In the early years of New Zealand’s colonial government, voting rights were exclusive to men who owned or leased property. Women could not vote, and Māori were largely excluded from the system. The land wars were raging in the north.

“Transient people were excluded and, of course, gold miners were largely transient,” Atkinson said. “Many of them were living in tents, in shacks, some of them in Otago were living in stone huts that they’d built and even caves.”

The 20-year gold rush brought a world of riches to settler Otago. Dunedin leapt in size, as grandiose stone buildings rose around the town. For a brief period, it was the colony’s largest city. Infrastructure sprung up, and banks, jewellers, a university, bars and brothels opened across the province.

By the time women won the right to vote in 1893 the gold seats of Parliament had come and gone. Photo: RNZ / Alexander Robertson

It wasn’t long before many of these miners were hankering for representation, much like in Victoria.

“The towns were flourishing, and in a way, it’s often said about gold mining that the people who really made the money were the ones who had bars and brothels and all sorts of things to support the miners, rather than the miners themselves,” said Atkinson.

“They were really fighting for their rights to be seen as legitimate citizens.”

In 1863, the number of people had skyrocketed from a few hundred to 24,000 (there were only 30,000 electors in the entire colony, Atkinson said). But the number of convictions also went up four-fold.

Every day, newspapers devoted pages to the previous day’s list of convictions in the goldfield settlements: Beatings, drunkenness, assault, drunkenness, indecency, drunkenness, theft, drunkenness, highway robbery, and drunkenness.

According to a story in the Otago Witness, one judge lamented: “The proportion of crime to population is at present very high in this part of the colony.”

To many, the influx of miners was seen as more of a headache than a boon.

The owners of the giant sheep stations on Central Otago’s barren, rolling hills and mountain valleys - who became known as the wool lords - did not want a rabble of diggers sullying their electorates.

Steven Eldred-Grigg’s 2009 book, Diggers, Hatters and Whores: The story of New Zealand’s Gold Rushes, detailed a growing battle between the diggers and the wool lords.

“Spiky spools of barbed wire were unrolled across the tussocklands. Many wool lords fought diggers with fire and whips … Tents were flattened and huts were put to the torch. Both diggers and owners sent spokesmen to Dunedin to lobby.”

It went on to detail an unfolding battle between the landed gentry and miners. Those who held sway over the colonial administration feared that a tidal wave of gold seekers would “swamp gentlemanly government and make politics a morass of rowdy democracy.”

But conscious of what had unfolded in Australia, and also the need to placate their supporters in the colony’s richest province, a method of representation was cooked up to try and blunt them.

“They created in 1862 an electorate called Goldfields District which covered that big area of Central Otago,” said Atkinson. “It was superimposed on top of the existing general electorates.

There are now 120 seats in Parliament. None of them are gold. Photo: VNP / Daniela Maoate-Cox

“So if people owned property, if they qualified, they’d vote in those electorates. But the gold miners could vote in Goldfields District,” he said.

“Then in 1865, they created a new one as well called Goldfield Towns. It was a very strange thing because it’s 10 separate towns, the places we know very well today: Arrowtown, Alexandra, Queenstown, Roxburgh, Clyde, Cromwell.”

These electorates provided the first form of representation for those who did not own or lease land, provided you were a British subject.

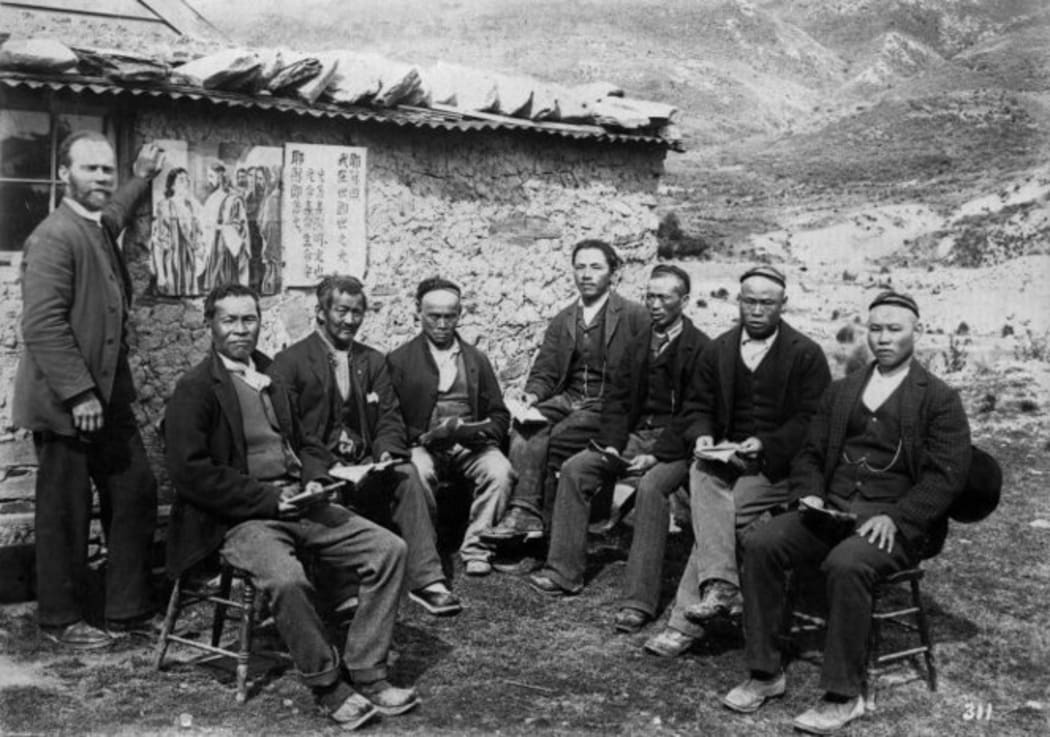

“A large number of Chinese had come into the gold fields,” Atkinson said. “A big Chinese population was completely excluded, subject to increasingly virulent anti-Chinese policies that restrict their immigration over time.”

Chinese gold miners and Reverend Alexander Don at the Kyeburn diggings, Otago Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library

So for a while, Otago had a complex landscape with three layers of electorates: Goldfield Towns was superimposed on top of Goldfields Districts, which were both on top of the general electorates.

The 1860s was a tale of two New Zealands. While Otago was reaping riches from the earth, the north was in the grips of the land wars, where the colonial government was struggling against Māori fighting to defend their land.

And here, Atkinson said, is where a parallel can be drawn between gold miners and Māori: they were both seen as a problem that would eventually go away.

Atkinson said the creation of the goldfields electorates proved a fitting template for a form of Māori representation, where a few seats could be created to pacify their calls without upsetting the balance of parliament.

Many settlers thought the gold miners would soon go away, and that the Māori population would soon be extinct.

“Māori and gold miners were seen as temporary problems to deal with,” Atkinson said. “The goldfields seats, with this idea of superimposing a seat on top of existing seats, was exactly what happened with the Māori seats.”

In the case of the goldfields electorates, their predictions came true, and the electorates were abolished in 1871. The rush only lasted about 15 years and had largely fizzled out.

Yet their legacy can be found in many places, including the electoral system.

“The way the gold miners were treated … was really the genesis of the Māori seats,” said Atkinson.

“Whatever the early history of those Māori seats, which were intended to deal with a problem, they were the one thing that survived from this period for 150 years.”