The Beatles 'White Album' is 50 years old and there's a new 6-disc edition to mark the occasion. Nick Bollinger takes a deep dive.

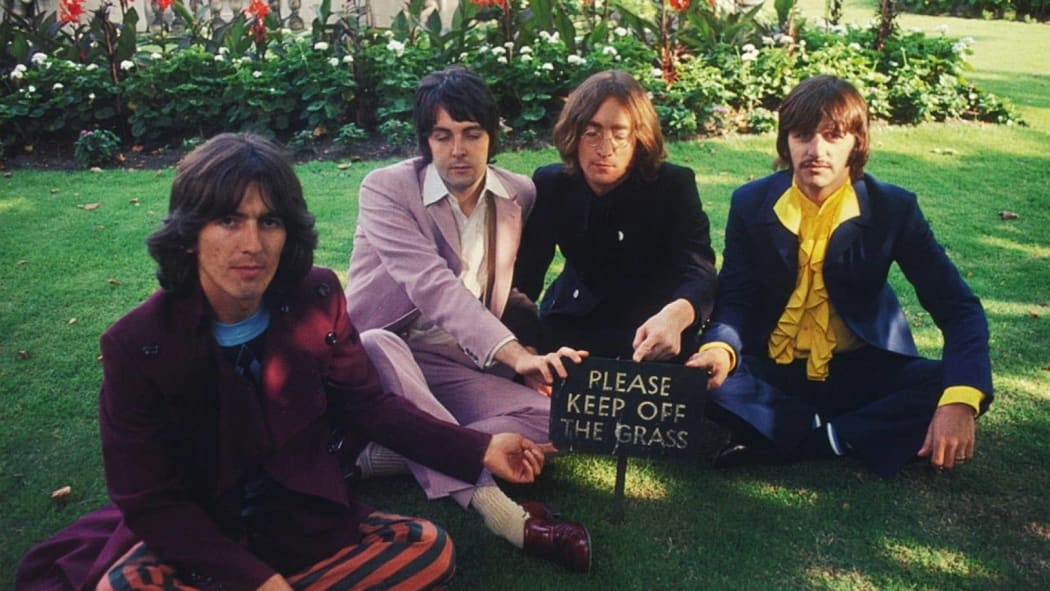

The Beatles, 1968 Photo: supplied

It’s 50 years this week since the release of The Beatles, or the White Album as it has come to be known, and the Beatle machine hasn’t missed the opportunity to sell those half-century-old sounds all over again.

But if you first bought this iconic double album in 1968, or in 1987 when it was issued for the first time on CD, or in any of the further iterations that have come out since then, has this latest version got anything new to offer?

Well, for one thing it does sound really good. The 2009 edition had been remastered, but this one has been remixed, by a small army of engineers overseen by Giles Martin, whose father the late George Martin produced the original record. Now, this isn’t a remix in the urban dance sense, where the original recording is essentially the raw material for a new piece of music. In fact, listening to Martin’s 2018 mixes you could be excused for thinking nothing had been done at all.

But play it side-by-side with, say, the original vinyl and you will hear what Martin has done. Back in 68, the Beatles were pushing the technology to its limits to create the unorthodox textures they were after. Taking those original mixes as his templates, Martin has used today’s technology to sharpen or more clearly define those textures. You could even argue that he has at last brought into being what the Beatles were striving for at the time. Unless for some reason you have never heard this record before, it won’t sound unfamiliar. But it might feel as though you’ve had your ears freshly syringed.

The Beatles: the 50th anniversary deluxe box set Photo: supplied

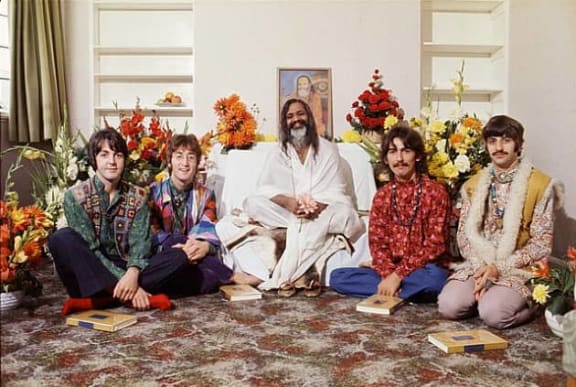

The reissue comes in several versions. There’s a 3-disc version, which gives you the original 30-song album in its bright new mixes, plus one extra disc of recordings made in May 1968 at George Harrison’s house in Esher, and these raw, all-acoustic performances are revealing in their own ways. The Beatles had spent the early months of 1968 in the foothills of the Himalayas, studying mediation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

The Himalayan outing had an audible effect on the music. With only acoustic guitars, the songs they wrote there, perhaps out of necessity, took on a folkish quality. Donovan, a fellow guest at the ashram, taught John Lennon the fingerpicking technique he employs on ‘Dear Prudence’ and many other tracks.

But the songs themselves reflected the mood in those mountains. There’s John Lennon assuring Prudence that she is a ‘part of everything’, and Paul McCartney portraying himself as a kind of Siddhartha in ‘Mother Nature’s Son.’

‘The deeper you go the higher you fly’ and ‘Come on is such a joy’ Lennon sings in ‘Everybody’s Got Something To Hide’. George Harrison once remarked that the lyric was made up almost entirely of quotes from the Maharishi’s teaching. That is, apart from the bit about the monkey. And there are similar Maharishi-isms scattered through the songs.

The Beatles with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Photo: supplied

The Esher demos are a great bonus, but for the deeper diver there’s the deluxe edition – which in addition to the three discs mentioned so far included a Blu-Ray with both mono, stereo and 5.1 mixes of the album, plus three more discs of material unearthed from the original studio tapes. And for me, this is where the real revelations lie.

Once the Beatles got into the studio, some of the pastoral qualities of the demos remained. But they also reverted back to being a driving rock’n’roll band; a skill they had virtually set aside after they stopped touring in 1966, in favour of baroque studio creations like Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour.

In these early takes and run-throughs, we hear those familiar songs before all the pieces of the puzzle have found their place. ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, one of George Harrison’s greatest songs, was tried in a number of different ways before Harrison finally brought in his friend Eric Clapton, whose weeping guitar provided the obvious counterpoint to George’s mournful lyric. But of course the version on the record wasn’t Clapton’s first pass at the song. And here we find a slightly earlier take (take 27, as it is labelled) on which Clapton plays with equal intensity.

Non-guitar nerds might be more curious about the brief segment where Paul McCartney seems to be sketching out what would eventually become ‘Let It Be’. Disturbingly the celestial figure in this version is not Mother Mary but rather Brother Malcolm. Could that be a reference to Malcolm Evans perhaps, the Beatles’ legendary minder? If so, it has never been mentioned in any of the mass of literature I’ve read on this song. But it’s just one example of the endless rabbit holes this latest peek into the archives opens up.

The Beatles, 1968 Photo: supplied

One of the questions that has been debated over the years is did they really need to make it a double? Weren’t they being a bit self-indulgent? Might it not have been better trimmed down to two punchy sides of a single LP? My feeling has always been that overload was the whole point. Unlike Sgt. Pepper, which simulated a concert experience right down to orchestral tune-ups and crowd noises, the White Album wasn’t necessarily made to be consumed in a single sitting and, even if it was, the effect was more like flicking through stations on a radio, or dipping into an enormous bag of different-flavoured sweets.

It’s also worth remembering that the ‘double album’ was, in 1968, very much de rigueur. The Beatles may have made the form their own, but they weren’t the first. After pioneering rock doubles like Bob Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde and The Mothers Of Invention’s Freak Out, 1968 saw a slew of two-disc magnum opuses. That year there was Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, Cream’s Wheels Of Fire. Even Donovan released a double, A Gift From A Flower To A Garden – all of which had an audible impact on the Beatles. I’ve already noted the appearance of Cream’s Eric Clapton and the effect of Donovan on Lennon’s guitar playing. To imitate Hendrix would have been a greater stretch, still in some of the most flamboyant guitar-brandishing of their career, you can hear the Beatles were hardly immune to his influence. Hear the blitzkrieg of ‘Helter Skelter’.

Though everything they did was touched by a unique Beatle-ishness, they were ravenous mimics, and sometimes you don’t have to look further than the music of the day to see what it was they were mimicking.

Lennon and McCartney grew up in a pre-rock era. The first songs they knew were the pop hits of their parents’ generation, and they would hark back to these in songs like ‘Honey Pie’. In 1968 the pre-rock songbook was enjoying something of a revival in the hands of the ukulele playing, falsetto-singing eccentric Tiny Tim, whose version of ‘Tiptoe Thru The Tulips’ had been a crossover hit that year, and that’s surely who McCartney is paying lip service to in the falsetto middle section.

1968 was also the year in which British blues reached critical mass, and while Clapton was its biggest star it was a new group formed by guitarist Peter Green and named after the rhythm section of Mick Fleetwood and John McVie that was surely in Lennon’s mind when he came up with ‘Yer Blues’.

Fleetwood Mac, 1968 Photo: supplied

When Lennon performed the song as part of the Rolling Stones’ Rock’n’Roll Circus just a few weeks after the White Album’s release, he even named the ad hoc line-up – which included Clapton and Hendrix drummer Mitch Mitchell – The Dirty Mac. (Fleetwood Mac would record a double album Blues Jam At Chess early the following year.)

Also doing a double in 68 was one of the Beatles’ more obscure yet palpable influences, The Incredible String Band. A pair of Scottish musicians Robin Williamson and Mike Heron, who played everything from harpsichords to sitars and were sometimes accompanied by their girlfriends Rose and Licorice, their instrumental palette might be reflected in some of the White Album’s more folky, acoustic-based tunes. But as songwriters, their effect is perhaps most noticeable in one of the White Album’s darkest tunes.

The Incredible String Band - Wee Tam Photo: supplied

The Incredible String Band’s songs often sounded like several entirely different songs woven together, and it’s a heavier version this kaleidoscopic effect that the Beatles’ achieve on ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’. With its irregular rhythms and abrupt switches of idiom, it is deliberately disconcerting – and that’s not to mention the lyric, which ominously takes its central metaphor from an ad for the American National Rifleman’s Association. Though clearly a Lennon song, Lennon needed a group as collaborative and versatile as the Beatles to play it. And the song evidently made an impression on his bandmates too. McCartney, who once named it as his favourite track on the album, would go on to emulate its multifaceted structure in songs of his own like ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ and ‘Uncle Albert’.

But it’s an album of contrasts, and in its original sequence ‘Happiness’ is followed by ‘Martha My Dear’, which finds McCartney at his most exuberantly tuneful. Here his fluid piano – which he augments with his own bass, drums and guitar as well as a hired brass band – is so lovely it hardly matters that the lyric is essentially made up of pretty platitudes.

There’s both whimsy and surrealism to be found on the White Album, but what about reflections of the wider world? After all, this was 1968: historically a year of worldwide turmoil. America was escalating the Vietnam War; Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis; students in Paris were bringing France to the brink of revolution.

Lennon, always the most political and outspoken of the Beatles, clearly felt the need to say something, though he appears to have been hedging his bets. In ‘Revolution’ he hasn’t made up his mind whether destruction was something for which he could be counted in or out; he mouths both words, one after the other. (In fact, he never did make up his mind.)

If he was more decisive as an artist than as a politician, his most profound artistic statement on the subject can be found in the album’s most challenging track, ‘Revolution 9’.This piece of musique concrete is the album’s penultimate track, goes on for nearly 9 minutes and remains confronting fifty years on, even if your ears have been hardened by the sonic bricolage of Kendrick Lamar or Kanye West. It’s certainly a measure of how far, by 1968, the Beatles had stretched the notion of what a pop album might contain.

In a final sweeping contrast comes ‘Good Night’, the album’s closing track, another throwback to pre-rock songwriting, written by Lennon but sung by Ringo, to a lavish Hollywood-style orchestral and choral arrangement courtesy of George Martin.

The White Album wasn’t The Beatles last recording, though by the time it was finished the Beatles final session as a foursome would be less than a year away. At the time of its release Ringo Starr, the eldest Beatle, had just turned 28. George Harrison was still only 25. Listening to this record with that in mind, let alone considering the entire body of work they had already produced, is impressive to say the least.

And for all the forensics that have gone into this latest edition, the experts still don’t seem to be able to agree on what it is they have heard. In one of the several essays in the lavish accompanying book, John Harris praises McCartney’ bass part on ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’; elsewhere in the package it is Lennon who is credited as bass player on this track. Half a century after its original release, the Beatles’ White Album remains a musicologically intriguing as well as deeply entertaining piece of work.