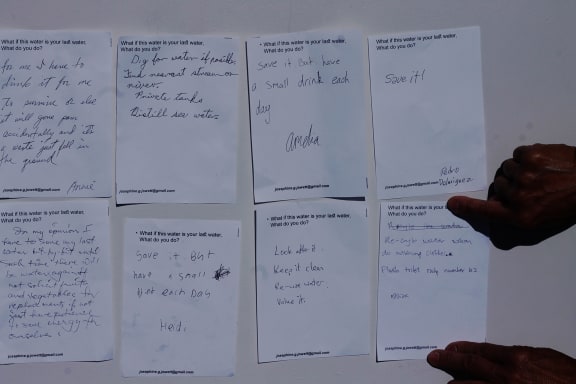

As she stands on the banks of the Hutt River under a sweltering sky, Josephine (Jojo) Jowett asks; “What you would do with your very last plastic bag of drinking water?”

Jojo is New Zealand’s first major Filipino installation artist. Her latest interactive art work 'Aftermath' involves several thousand plastic bags of water and the public’s participation.

She was inspired to question the act of collecting water after growing up in poverty in her birth country.

Subscribe to Voices for free on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

Free public entertainment is taking place in the square outside the Dowse Art Gallery in Lower Hutt. People are filling up large plastic containers with pure, ice-cold water from two pumps directly linked to the much sought-after Waiwhetu artesian aquifer beneath Hutt Valley.

At a time when New Zealand faces critical issues related to climate change - including water quality, ecology and ownership - a partnership between ground-breaking public art producers Letting Space and Hutt City Council have created Common Ground: Hutt Public Art Festival 2017, which explores our environmental relationship with water in new ways through art.

“I used to wash in the Philippines, in the Suba river of La Castellana Negros Occidental . Every morning, there’s no tap water, it’s only a few people who can afford to have [piped water], really, so this is where we wash every day in the mornings, in the rivers.”

Born 1959 in Negros Occidental in the Philippines as one of nine siblings, Jojo spent an idyllic early childhood in Cebu city. Her affluent parents owned Cebu’s largest sweet factory.

“In Cebu – it’s more buying; you have to buy water in containers because there’s no running water for poor people.”

But then disaster struck. The family home and factory in Villagonzalo II, Cebu burnt to the ground while corrupt firefighters looked on. She says it was in that moment that the concept of “water” took on a profound meaning for her.

“Everyone was screaming for help, but the firemen just want to collect some money and then they will save our house. We lost everything, and the whole neighbourhood, 90% of the population disappeared. And that’s where my life changed.” Only a week later their temporary housing was destroyed by a typhoon.

Jojo remembers seeing her parents struggling to pick up their lives every time they experienced disaster. The family were suspected to be cursed.

“People were very superstitious, they did not want us in their homes after our fire, as if we would bring them bad luck. My artwork is like a scar, a reminder of my past.

“Plastic River - all the pollution is there, in Manila. You can’t drink from the tap because you get sick. We used to buy this [drinking] water in plastic bags. We don’t really know where the water comes from. “

And then the plastic bags become part of the pollution?

A child washes his face with laundry water among the trash and dogs in Tondo Landfill, Manila Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 / Adam Cohn

“Yeah – and then they become rubbish, we throw it away. And the pollution of the plastic... imagine millions of people. Then everything goes to the river and no-one cares about the river.”

As she says this, Jojo gazes down the sweeping, lush green of the Hutt River towards the horizon. The contrast is striking.

“You see the most beautiful, the most clean... You have one of the most..."

She struggles to find the words. She’s been living in New Zealand 27 years now, but English is still frustrating,

“Pristine?” I offer. “Yeah,” she replies.

“People like me are so lucky to have clean water, but by the time you look at this, you think about the pollution in the Philippines...”

Josephine (Jojo) Garcia Jowett on the banks of the Hutt River. Photo: RNZ / Lynda Chanwai-Earle

In spite of facing poverty as a child, Jojo’s parents were determined to give their eldest daughter an education. She dreamed of becoming an artist but instead became a licensed naval architect and marine engineer after studying in the University of Cebu.

Jojo met her husband, New Zealander Roy Jowett, while he was working as a boat builder there. The boatyard needed a naval architect and she was perfect for the job.

After they married Jojo and Roy traveled, deciding to live in Wellington. Tragedy struck again when he lost his life during an accident, leaving Jojo to bring up their two children on her own.

In spite of these challenges Jojo followed her dream to become an artist, gaining a Bachelor in Visual Arts from the Wellington Institute of Technology. She has been exhibiting in New Zealand since 2001 and in 2010 was presented with the Filipino Achiever Award by the Philippines Charge de 'Affaires.

Parabox by Josephine Jowett, Performance Arcade and London 2016. Photo: Denise Bachelor - artist/photographer.

“I believe looking backwards will allow me to move forward. My art always reflects my experience; I create something that may look negative to the viewer, but my intention is to see [the issue] in front of me and then do something about it.”

The irony contained within the making of 'Aftermath' is the purchase of the small, specially shaped plastic drinking bags from the Philippines. "We call it "ice water.""

I ask Jojo what she will do with all this plastic and she tells me she will store and recycle them within ongoing new works of art.

Previously exhibited at the Dowse Art Square, the Performance Arcade and the Sacred: Homelands Festival in London, Jojo’s 'Aftermath' installation appealed to the Common Ground Festival organisers.

Letting Space Curator Mark Amery tells me that he was very excited to have Jojo involved.

“What Jojo offers us is something really vital in thinking about the Asia-Pacific region. Those that have traveled through the Asia-Pacific will know how lucky we are to have our assets of clean water. If you look at the water in the Hutt Valley we think it’s extraordinarily good. This festival is as much a way of celebrating what we have as also criticising the powers that be.”