South Canterbury Finance's (SCF) former chief executive falsified a loan to another company to hide the company's risky lending, the High Court at Timaru has been told.

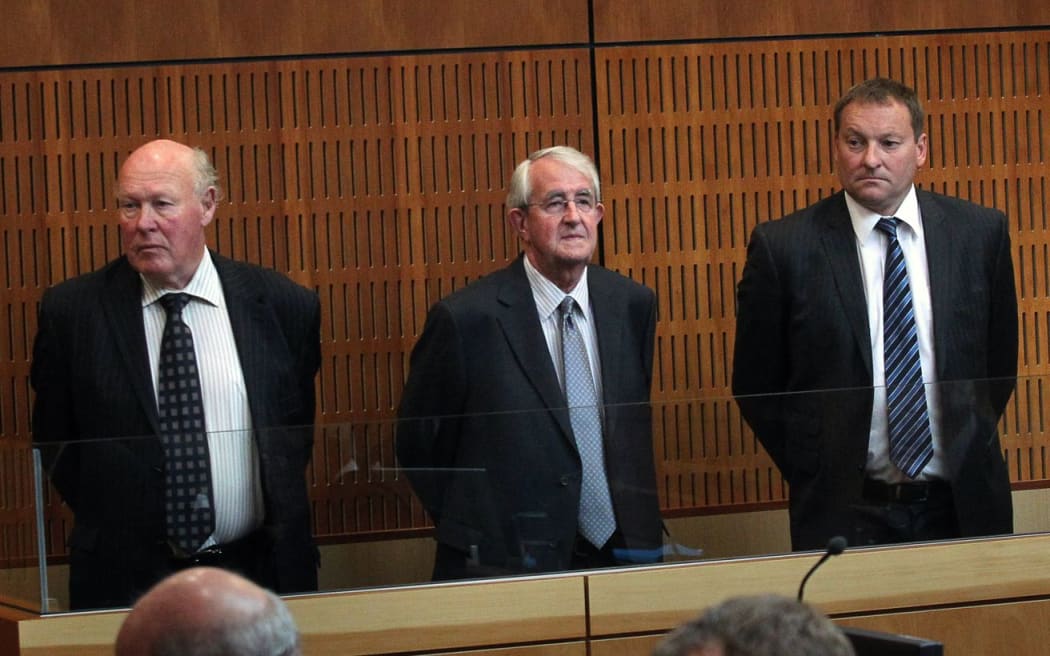

From left: Edward Sullivan, Robert White and Lachie McLeod. Photo: Mytchall Bransgrove

The Crown has opened the country's biggest-ever fraud trial in the High Court at Timaru against the former chief executive, Lachie McLeod, and former directors Edward Sullivan and Robert White.

The charges, brought by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), include theft by a person in a special relationship, false statements by a promoter, obtaining by deception and false accounting. All up the men face 18 fraud charges relating to the $1.6 billion collapse of SCF in 2010.

Five charges have been laid against Mr McLeod, a farmer and the company's chief executive from 2003-2009. Mr Sullivan, a director of the company for 20 years and former partner of a Timaru law firm, faces nine charges, while Mr White, who was a director for 16 years, is on four charges.

Before the Crown opened its case, lawyers for the three accused men asked whether Justice Heath should remove himself as the trial judge because of a perceived bias towards the SFO.

Jonathan Eaton, QC, representing Lachie McLeod, said this came about because of comments by SFO director Julie Read at a conference the judge attended, at which she it was lucky to have him as trial judge in the SCF case.

Mr Eaton said it wasn't a case of actual bias on the part of the judge but the perception of bias the comments created that was of concern.

But Justice Heath said the remarks were not enough to leave an impression in the mind of an ordinary member of the public that he held a bias toward the SFO and ruled the trial could continue.

Impact outlined

Once under way, Mr Carruthers outlined the nature of the charges and the impact the alleged offending had on the performance of the company.

He said the company's directors and managers ignored or evaded important controls which should have regulated how the company operated.

Some of the offending involved falsified and backdated entries in a journal, including a loan from SCF to Kelt Finance by Mr McLeod. Kelt says it has no record of this transaction.

Mr Carruthers told the court a hallmark of the offending was a series of related party transactions designed to hide high-risk lending.

"This approach to the management of the affairs of the company moved beyond the merely cavalier to the dishonest. That attitude materially contributed to the collapse of the company," he said.

Mr Carruthers laid out a series of transactions between SCF and companies it had a relationship with, such as Shark Wholesalers - a company which was under the control of Mr Sullivan but had no employees and was solely for the purpose of trading in shares.

He said it was crucial that the three accused had failed to declare these transactions in the SCF prospectus; the document investors were supposed to be able to rely on when weighing up how much of a risk a company was as an investment.

It was also the document the Treasury relied on when it decided in late 2008 to include the finance company in the government's Retail Deposit Guarantee Scheme.

The trial is expected to run until June.