Market meltdowns are nothing new. Here are ten of history's worst, linked by one common theme; what goes up must come down.

The South Sea Bubble

The South Sea bubble caused panic among London's Georgian investors. Photo: Wikicommons / William Hogarth

This 1720 crisis gave us the term "bubble."

The South Sea Company had a monopoly on trade with Spanish South American colonies, which was granted by the British government in exchange for taking over national war debt.

Its shares started to rise and rise on the back of its own spruiking of eye-watering South Sea riches.

It convinced the British government to allow it to assume more national debt in exchange for its shares, boosting them to £330.

A subsequent flurry of stock market speculation led to Parliament passing the "Bubble Act" in June which required all companies to receive a royal charter.

The South Sea Company received its charter, seen as a vote of confidence, and by the end of June its share price reached £1,050.

But investors lost confidence and by September that year the shares had plummeted to £175.

US joins the party with the Panic of 1792

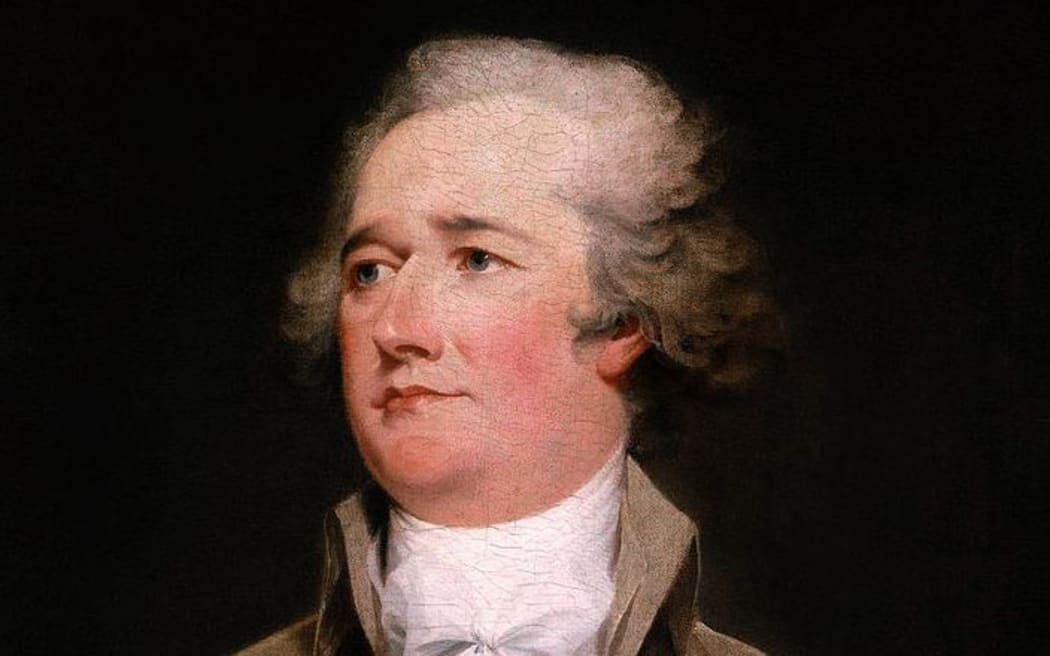

Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary of the United States. Photo: Wikicommons

This was the USA's first financial crisis. It was caused by a credit expansion by the newly-formed central Bank of the United States (BUS) and speculation by some dodgy bankers.

The bankers contrived to drive up the prices of US debt securities and bank stocks. Meanwhile, the BUS was lending money freely, much of which was spent on further speculation.

When the BUS ran low on hard currency, it reined in lending and markets fell 25 percent in a fortnight. The crisis led to Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury secretary of the United States, engineering that country's first bank bailouts.

The first emerging market crisis

Trading nation:British investors hope to make fortunes from the new world. Photo: Wikicommons

In 1825, the industrial revolution was in full swing and Britain was booming so cashed up investors were looking for somewhere to park their new found riches.

Foreign bonds offering attractive returns by governments in the New World caught their eye.

Newly independent nations such as Chile, Peru, Mexico and Guatemala sold bonds worth billions on the London market. British mining companies looking to exploit the Americas also saw share prices surge.

Inevitably bond prices plummeted as the shaky finances of those countries were gradually exposed. Some bonds fell by as much as 40 percent leaving Britain's banks exposed, and a bank run followed.

The Bank of England jumped in to bail out collapsing lenders and exposed firms.

Going off the rails - the first global crisis

Victorian Investors got their fingers burnt when they piled into US railways. Photo: Wikicommons

1857 saw the first tech bubble and first global financial crisis when British investors piled into American railway firms.

The railway companies' share prices bore little relation to their earnings but investors were betting on future profits.

As US railroad firms started to fail, first US banks and lenders, then their British counterparts were left exposed.

By the end of that year £42m of British investor capital had been wiped out.

As the world's first financial hub, Britain's woes spread to other markets. Economic contagion was born.

Banks, but not banks; the "Knickerbocker" crisis

By 1907 the US had started to develop a highly decentralised banking system - its first central bank (BUS) had long since closed.

There was an explosion of new banks and less regulated trust companies at the end of the 1900s.

The trust companies started to behave like banks but didn't need to hold as much cash in reserve - 5 percent versus 25 percent.

They also offered more attractive returns to investors and so grew exponentially - as did the wider US economy.

Two rogue bankers, meanwhile, tried to corner the shares in a copper company with fraudulently-acquired money, but raw material prices fell, as did share prices in the copper company.

The Knickerbocker Trust, the third largest in the US, was caught up in the spreading crisis.

Its depositors demanded their cash, setting off a run on trust companies and then banks.

The crisis led to the US returning to a "lender of last resort" model and its third and existing central bank, the Federal Reserve, was born.

The Big Daddy crash

As the roaring 1920s came to a close, the Federal Reserve, formed 16 years earlier, was grappling with the problem of surging share prices but dropping consumer prices - should it cut or raise rates?

It raised rates in 1928 from 3.5 percent to 5 percent with disastrous results.

The move failed to cool Wall Street, but put the brakes on the far shakier real economy - industrial production plummeted.

The Wall Street crash of 1929 Photo: Wikicommons

Shares continued to make merry, hitting a high in September 1929.

This financial own goal in the US was compounded by a fraudster-originated crash on the London Stock Exchange.

A sell-off ensued and Wall Street lost 25 percent in two days and almost half its value by November of 1929.

A wave of bank failures followed that peaked in 1933 when the Federal reserve again fluffed and refused to lend to struggling banks - thousands of banks collapsed and the Great Depression began.

The first "Black Monday"

Greed is good? Wall Street saw its biggest one-day drop in October 1987. Photo: AFP

On October 19, 1987, The Dow Jones industrial average plummeted by 22.5 percent and £50 billion was wiped from the London market.

The stock price falls started in Asia and spread quickly, helped by new automated trading systems.

By the end of October, markets in Hong Kong, Australia, Spain and Canada had plunged. New Zealand's market fell 60 percent.

However this crash had few effects on the wider global economy and the Dow recovered to its previous high by 1989.

The "tigers" catch a cold

Also called the Asian Contagion this was a series of currency devaluations and asset price crashes that spread through Asian markets in 1997.

It started in Thailand as the result of the government's decision to no longer peg the Baht to the US dollar.

Currency declines spread rapidly throughout the region, in turn causing stocks to crash, and political upheaval.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) stepped in with a $US40 billion program to stabilise the regions' economies.

The e-crash burns blue sky investors

The first crash of the digital age, in 2001, saw 78 percent of the NASDAQ's value lost as investors became over-excited by the "New Economy".

Digits were burned in the 2001 dotcom crash. Photo: AFP / FILE

Internet start-ups were everywhere, simply adding an "e" prefix was enough to part tech-mad investors from their cash.

Just as in the rail road crisis 150 years before, company fundamentals were overlooked; bold, blue sky thinking was in.

But the dot-coms started to leak money and fold. From a peak of 457 start ups in 1999, the figure dwindled to 76 by 2001.

The last 'big one'

The 2008 financial meltdown was triggered by complex US mortgage-related securities which, when the US housing market crashed, sent world markets and economies into a spin.

By the end of 2008 the sub-prime mortgage crisis had infected share markets - which in the US were down 20 percent on their peaks.

US financial royalty in Bear Sterns, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac wobbled and were bailed out. Lehman Brothers, overexposed to the toxic derivatives, filed for bankruptcy - the largest in US history at that time.

Some exposed British banks were "nationalised" by the government. Meanwhile central banks slashed interest rates and started to print money as European and US economies stalled.

What started as an obscure US sub-prime problem threatened nation states and massive loans were approved for Greece, Ireland and Portugal to stop their respective economies from collapsing.

Blood on the trading floor: Wall Street 2008. Photo: AFP