As Syrian families are arriving in Germany, I find myself remembering the places and moments of our first year there, while we were being 'processed'.

Outside the block of flats where Veronika Meduna's family spent their first year - her mother on the left, Veronika and her grandfather on the right. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

I was nearly 10 and my parents and I had escaped from what used to be Czechoslovakia.

The author today Photo: RNZ

After a few days of being moved between different places, we were finally sent to a small city in southern Germany where we had been allocated a room in an "Auffanglager" (catch camp) - a block of flats that housed refugee families from many different countries, one family per bedroom, around a dozen people in each flat, all sharing the kitchen and bathroom.

Ours was a time when eastern and western Europe were two very different worlds.

Unlike people who tried to cross from east to west in the divided city of Berlin, where the boundary was enforced through razor wire, bullets and minefields that lay to the east of the Berlin Wall, we didn't risk our lives.

Our risk was imprisonment if we got caught, and the possibility that only one of my parents would make it.

It was a few years after Soviet tanks had rolled into Prague to crush a political liberalisation movement known as the Prague Spring.

The sight of tanks thundering down the cobbled streets of my home town on their way to Prague early on 21 August 1968 is one of my earliest childhood memories, reinforced and no doubt embellished by family stories that continue to this day.

For two weeks afterwards, the borders remained open and hundreds of thousands of people fled, among them many writers, artists and anybody who could not envisage a life without the freedom of thought and expression that had begun to blossom in the preceding years.

My parents decided to stay. They were young, had a three-year-old to worry about and simply hoped that things would turn out OK enough.

Tanks on 21 August 1968 as a Soviet-led invasion crushes the so-called Prague Spring in former Czechoslovakia. Photo: CTK / AFP

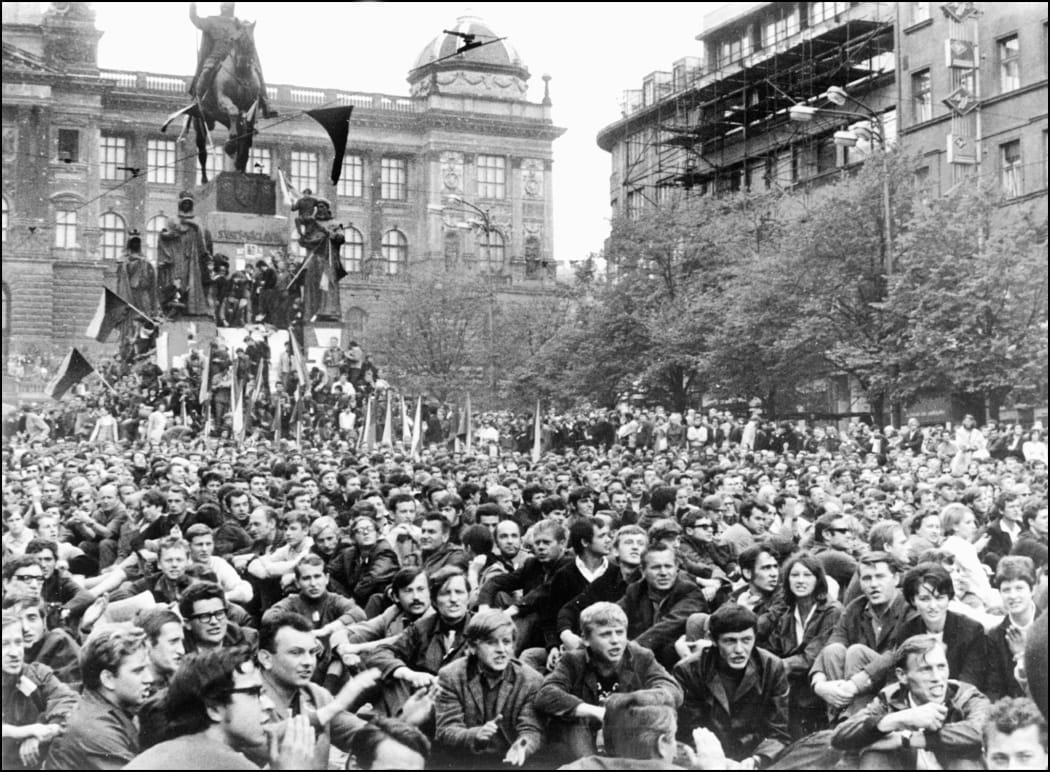

Prague residents hold Czechoslovakian flags in Wenceslas Square in August 1968. Photo: CTK / AFP

Six years later, in 1974, it was clear that things hadn't turned out OK, and that oppression was mounting against those who didn't actively support the Communist party or had German heritage. So they left, along two different routes and at different times to avoid raising suspicion, and with no more than a bag each.

I was travelling with my mother by train, with an official invitation from my grandmother who had emigrated to Germany years earlier when it was still possible.

We were only allowed to travel because my father stayed back - a human insurance policy that would encourage our return. But as soon as we left the train station, he started walking towards the border.

I had no idea we were escaping. I was only told that we would never return once my parents were reunited in Germany, safe in the knowledge that we had made it.

The Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 forced many residents to flee for other parts of Europe. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

For both our escape and our first year of resettlement we depended almost entirely on the kindness and generosity of others. There were of course the school bullies, xenophobic neighbours and resentful workmates, but decades later, they don't occupy much of my memory.

Instead there is the man who drove his car all the way to former Yugoslavia, which didn't belong to either NATO or the Warsaw Pact and provided a frequently travelled route for people trying to reach the west.

He carried his wife's passport and met my father at the Austrian border. His plan, or rather hope, was that they would be lucky - that driving a car registered in Germany and holding two German passports against the car window would be enough to be waved through the borders of Austria and Germany.

It worked. If it hadn't, I wouldn't have seen my father again for years to come.

There is the woman from a charity organisation who would drop off donated clothes for all the people living in the resettlement flats.

For me, these occasions were like an invitation to a dress-up party, and I was playing with a handbag when I found a 10 Deutsch mark bill inside. She just smiled and told me to keep it because who ever had left it in there would have wanted me to find it.

The last image of the author and her parents in Czechoslovakia, taken a few weeks before their escape. Photo: RNZ / Veronika Meduna

There is the principal who told my parents that my presence had lowered the achievement level and ranking of the primary school I started attending, only to apologise six months later once he realised just how quickly kids can learn a new language.

There is the five-strong Russian family living in the largest room of our flat. In a random shuffling of families, we had ended up living next door to people we thought of as enemies, the reason why we had left our home in the first place. Us kids didn't care - and after a while the grown-ups didn't either.

There is the employer who gave my father work three weeks after we arrived, even though he had no way of proving his qualifications and couldn't speak German.

There is the next employer who gave him a better job because he knew that when people start afresh, they want nothing more than to return to at least some level of normality.

Some can never go back

It was my parents' decision to leave; but one of the hardest things to live with, for all of us, was the thought that we might never be able to return.

For almost two decades, setting foot in our home country would have guaranteed swift imprisonment. At the time, nobody foresaw that the Berlin Wall would fall, that communism in eastern Europe would collapse, and that a dissident poet would be elected president of Czechoslovakia, and later Czech Republic.

One of Vaclav Havel's first acts in office was to issue an amnesty for all those who had escaped during the Communist era. Almost exactly 16 years after our escape, we were standing in a long queue of people at the border, waiting to make the first of our visits back.

I feel lucky - many refugees never get the chance to return.

Veronika Meduna is a producer and presenter for Radio New Zealand science programme Our Changing World. She joined Radio New Zealand in 1999.