Canterbury's regional council says it now has the enforcement tools needed to deal with farmers enchroaching public land and it won't hesistate to use them.

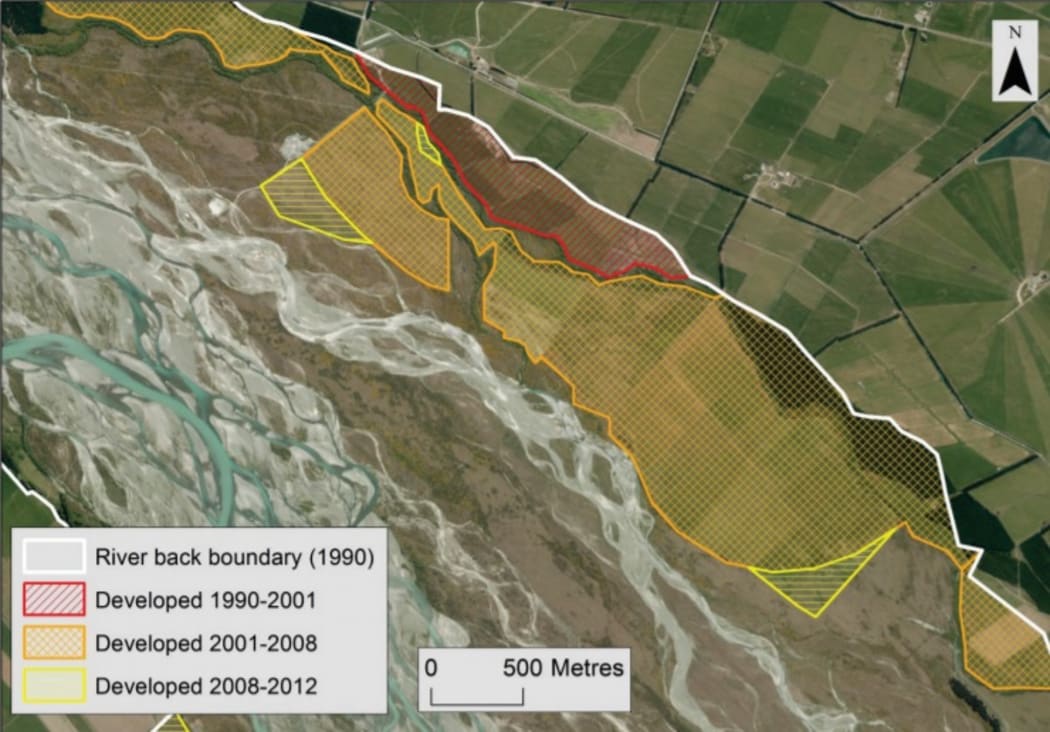

Aerial photograph showing river margin vegetation clearance and land use change in the lower Rakaia River. Photo: Supplied

An Environment Canterbury report has revealed almost 12,000 hectares of land beside Canterbury's braided rivers was been converted for intensive agriculture between 1990 and 2012.

One-quarter of the land developed for farming was in public reserve.

Jen Miller from Forest and Bird has said it amounted to basically stealing public land.

A programme manager for the council, Don Chittock, says braided rivers were incredibly valuable and a high priority in a lot of the council's work.

Some development did not require consent, but others did and there had been cases where consents had been exceeded.

"The key thing is, now we've got examples, we have taken enforcement action and are ensuring that people stop those activities.

"And at least in once case they are going to put things back."

Mr Chittock told Morning Report a land and water regional plan was introduced in 2016 to provide a "rule book" and the council would use its enforcement tools.

"We've got a case in point where we've done that, in the Selwyn River, where we stopped someone doing that work."

The regional council's report details the widespread conversions, called agricultural encroachment, on the margins of 24 of the region's braided rivers.

The Waimakariri River Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The report described the rivers as as "internationally and nationally significant", a "defining characteristic of the region's landscape" and "critical habitat for remaining indigenous biodiversity."

In the 22 years from 1990, 11,630 hectares of that riparian zone was converted for intensive agricultural use.

Although the majority of the land was privately held, a quarter was public reserve, and the rest (16 percent) was unallocated.

Mr Chittock said the council was also working with groups and landowners in around the Rangitata and Waiau rivers.

Federated Farmers' environment spokesperson Chris Allen said in some areas the encroachment may have been legal and approved, such as by Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) or the Department of Conservation (DOC), so may be entirely appropriate.

Braided rivers were particularly complicated as the water channels moved and could leave wide berms, so farmers had to have a very clear understanding of the rules on which sections of the land could be used.

Mr Allen said if any farmers were found to be in violation of the rules it would be an expensive job to remediate the land.

Jan Miller, the Canterbury/West Coast regional conservation manager for Forest and Bird, said agencies such as LINZ and the DOC were "failing to do their job". She questioned whether they were more interested in an economic growth agenda than their function around protection.

What concerned her was that the same thing was happening in the high country in areas of important habitats for native species, she said.

The report noted that most of the riparian land on the Canterbury plains had already been developed, and similar development was now starting to happen upstream in the high country valleys.