Sometimes joining the world of salaries and annual leave is tougher than expected.

Mava Moayyed found herself on the hamster-wheel of joblessness bad feels after coming back from an internship in Asia. Photo: Alexander Robertson/The Wireless

Last year I spent the better part of seven months looking for work. I wrote more cover letters than I can remember, had my CV professionally re-designed, and received so many generic rejection letters I could recite them by heart.

I didn’t think I’d struggle to find work. I never had before. I joined the workforce when I was 14 – a year before I was legally supposed to – working the weekend shift at a small café on the beach, earning a glorious $7.50 an hour and eating my weight in ice cream. All through my university years I’d worked odd jobs in retail and hospitality, landing them with relative ease, my wide-eyed optimism serving me well. I was acing life.

But this time was different. This time sucked. I left the world of low-paid shift work and tried to join the “grown-ups” with their fancy yearly salaries and annual leave. Except they wouldn’t let me in. It was like not being picked for a team in a game of ultimate frisbee, ending up alone on the side of the field, and just staring longingly at all the other people having the best time.

Photo: Unknown

As tough as it was for me personally, statistics show that it would have been worse a few years ago. The reality is young workers are more vulnerable to downturns in the labour market because of lower skill levels and limited work experience. Youth unemployment in New Zealand reached nearly 20 per cent during the latest economic crisis. Rates have fallen to about 14 per cent, just over Australia’s 13 per cent.

The picture is much grimmer in Europe. Over half of Spain’s youth are unemployed and Greece, a country whose financial meltdown has made headlines since 2009, has a youth joblessness rate of nearly 60 per cent.

The part that really stung was that I had just spent a year with 24 other people learning to be journalists. Then they all got jobs. That’s not an exaggeration; everyone became gainfully employed. I went off to Singapore for an internship, certain it would help my chances of getting the most bad ass job in the class, except it didn’t and I spent my first few months back in New Zealand pretending I was super busy doing all my important unemployed things. (Like sleeping at inappropriate hours and keeping up with Australia’s Biggest Loser.)

At that point I decided it wasn’t healthy doing nothing even though it felt like an extended holiday at the time. I signed up for my master’s and inadvertently, got myself out of a potentially dangerous place – the NEET space.

NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) is an acronym created in the UK to more accurately gauge the numbers of jobless young people. It’s a good alternative to the traditional youth unemployment rate which doesn’t account for young people who are out of the labour force because of school or tertiary study. Its weakness is that it can’t accurately reflect the number of those actively seeking work verses those who aren’t.

Figures from Statistics New Zealand [pdf] say that in 2014 about 11.4 per cent of 15-24-year-olds fell into the NEET category. That’s about 72,000 young people out of school and out of work.

Several studies have revealed the damaging effects of prolonged “NEETism”, including 2014 research out of the United Kingdom [pdf] that found 40 per cent of jobless young people have faced mental health problems as a direct result of unemployment. The UK’s NEET rate sits above ours at about 13 per cent.

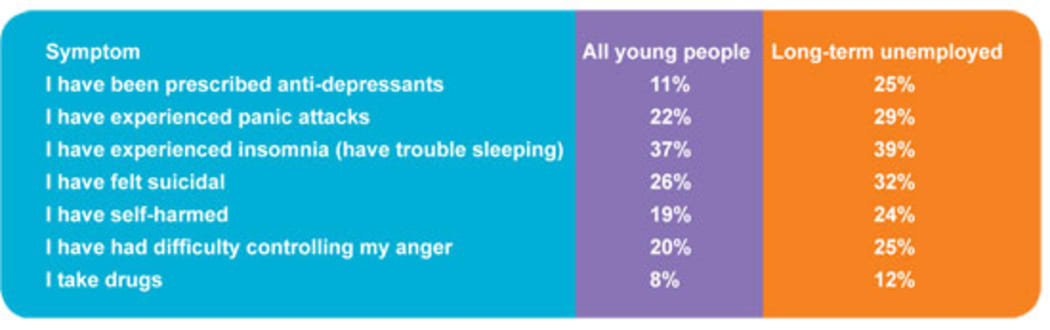

The research, carried out by the Prince’s Trust, also discovered that long-term unemployed youth were more than twice as likely to have been prescribed anti-depressants and 21 per cent believed they had “nothing to live for”.

Photo: The Princes Trust Macquarie Youth Index 2014

READ: Eamonn Mara writes about how having – and not having – a job affects mental health

For me, not having a job sucked but it wasn’t the lack of money; with each rejection letter I felt my sense of self-worth erode. I wasn’t successful or smart or desirable. I was in a constant state of panic that the longer I was unemployed, the more unemployable I became. Joblessness felt like being stuck on a hamster-wheel of bad feels.

Andrew Shierlaw, 30, is one of the half-a-million people who ended up across the ditch where the grass is statistically greener. But after an eight year stint, he’s back.

Landing a job at Wellington’s Fidel’s Café as soon as he got back, Andrew has been working as a barista for over half-a-year. Although he is really good at making coffee (I can attest to that, if anyone needs a reference) it’s not what he wants to be doing.

Andrew Shierlaw says the more rejection letters he gets, the harder it is to stay motivated. Photo: Mava Moayyed/The Wireless

Andrew worked as a service coordinator for public transport infrastructure in Melbourne but can’t seem to land a job that uses his skills in Wellington.

“It’s very demoralising. I guess because there is such a gap between working in hospitality to the corporate roles that I’m gunning for. I just don’t hear back from them and I’m finding it quite difficult to get the ball rolling.”

Anyone who has ever applied for jobs knows the process and emotions are cyclical. “I’ll get really motivated to look for work,” he says. “I’ll apply for jobs, I’ll talk to recruitment agencies, I’ll talk to companies and then after a while I start getting the rejection responses. The more they come in, the harder it is to stay motivated.”

Like my decision to get back to university in the midst of my unemployment, Andrew understands the value of staying engaged – outside the NEET space – and keeping busy.

“Personally I need the structure in my life to keep my mood stable,” Andrew says. “If I had a lot of free time I think it would be harder to structure my life in way that’s going to help put my best foot forward if I do get interviews.

“I definitely don’t want to be having a really bad time then go do an interview because that comes across.”

I was on a packed bus when I got the call. My immediate reaction was to emit a high pitch squeal; the kind you’d hear out of an excited three-year-old or a dodgy car brake. Midway through the phone call the bus broke down, but while the rest of the passengers were moaning about the inconvenience, I was making more squealing sounds and basking the in glow of my new employed self. My Australia’s Biggest Loser consumption is restricted to the occasional YouTube clip.

TOP 5 REASONS PEOPLE TOLD ME I WASN’T LANDING A JOB

- I was overqualified

- I was underqualified

- My name was really weird and whether they knew it or not, the employers were probably racist

- The job market was weak and journalism is dying

- There was no reason, it’s just luck