Being the victim of a crime can be a traumatic experience and it can also be an expensive one. So what’s the true cost of a crime? For some people, it’s a matter of replacing lost property. For others, it’s years of therapy, and endless cups of tea.

(Some of this article could be upsetting. Resources can be found here.)

Photo: Illustration: Pinky Fang.

Eighteen years ago, Karen* was asleep in her house, along with her two daughters. She awoke to the serial rapist Malcolm Rewa in her room. After he had raped her and left, she ran across the road to the home of a police officer. She would only go back to her house once more.

With her daughters in the care of a friend, Karen then spent what she says felt like a whole day at a busy police station - taken to the cells to have her fingerprints taken, and rarely left alone.

She remembers taking a break to go to the bathroom and breaking down. “It was the first time I’d been by myself since it had happened ... and suddenly I was alone, and I was in the police station toilets, and I just totally cracked up. I was a mess.”

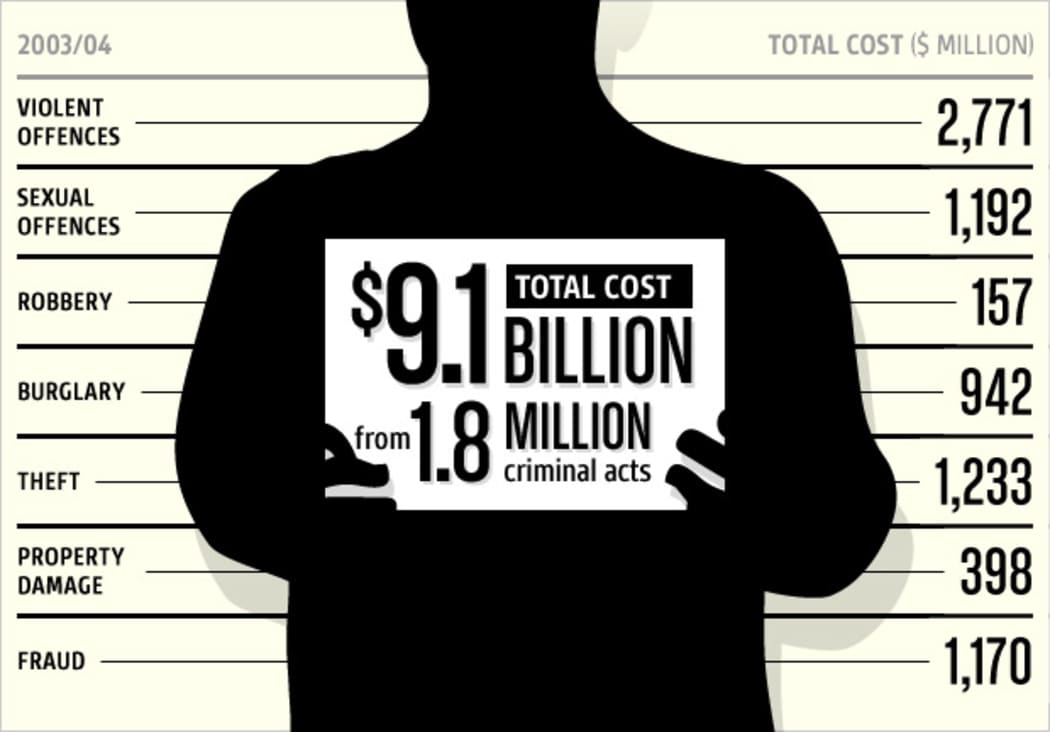

Whether it’s someone stealing your wallet or a violent crime, there will be a cost to the victim of a crime. A 2006 report by Treasury looking at the cost of crime in 2003/4 put the total cost at $9.1 billion. Of that, sexual offences were the most costly “primarily reflecting the impact on victims.”

The Ministry for Women estimates the annual cost of sexual violence as $1.2 billion.

The report measures the cost to the public sector - in the criminal justice and health sectors - and the private sector. For businesses and individuals, the cost of crime include the loss of property; taking time off work and the resulting loss of productivity; and “intangibles”.

“Intangible costs reflect the impact on victims’ quality of life through the physical and emotional effects of crime. While difficult to measure, these victimisation costs can be significant and need to be included in any calculation of the total costs of crime.”

The report puts the average cost of a sexual violation at $304,370, of which $172,040 is private costs. By comparison, the average cost of car theft, is $12,620, more than $10,000 of which is borne privately.

After her attack, police took Karen’s quilt cover as evidence. “I just didn’t want any bedding back or anything like that. When you talk about those kinds of costs, they’re just incidental things, but of course I had to buy all new bedding.”

“I just didn’t want any bedding back or anything like that. When you talk about those kinds of costs, they’re just incidental things, but of course I had to buy all new bedding.”

Kevin Tso, the chief executive of Victim Support, says there’s a whole range of costs to a person’s life. “Time off work, clothing, perhaps travel to go to another place, maybe home to Mum and Dad.”

Victim Support provides assistance up to $500 help with the emergency costs incurred immediately after the crime like replacing clothing, emergency accommodation and repairing or replacing damaged property.

Tso points to clothing, bedding and transport in the immediate aftermath of a crime or trauma. “Let alone the emotional support that we provide, which is probably the most critical thing.”

He points out that victim support volunteers also help with navigating the complex (and often traumatic in itself) process of reporting a crime.

Melanie Calvesbert, team leader of social work at Wellington’s Sexual Abuse Help foundation says most victims can’t tell what support they’re going to need. “Say it’s two days after the sexual assault, they couldn’t say ‘next week I am going to have trouble doing this, next week I am going to have trouble doing that.’”

She says the most common need for sexual assault victims is to replace clothing that has been taken by police, but that’s by no means the only thing. “It could be a cellphone. It could be to change where someone is living, because the assault happened at their flat, for example.”

Coincidentally, Karen was due to move three days after she was raped. For a long time she couldn’t even drive down the street it had happened on, and only went back to the house once before moving. “I hated it. I hated every minute of being there.”

She was also afraid of leaving the house, her children leaving the house, and was terrified of being alone. “I couldn’t sleep, and I was terrified of being by myself. We moved house, and I had my two daughters, but I had a succession of people staying with me, because I was too scared to be by myself.”

In the six months before Rewa was caught, she was also paranoid of being in the car, especially at traffic lights. “I kept thinking that I would see him. This person who I wouldn’t even be able to recognise, I was paranoid that I would see him in the car behind me.”

Photo: Illustration: Michael Greenfield

Having taken a couple of weeks off work, and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, Karen visited her GP and counsellor.

Wellington Rape Crisis’ Eleanor Butterworth says it can be difficult for victims to know what kind of help they need. “Often people present initially saying “I need help managing ‘this’ and then gradually we unpack all the other bits of that, whether it’s housing, benefits, those sorts of things, and trying to work with those organisations that do that.”

People often come in and say “I want counselling” when a different sort of treatment might be more appropriate, she says. “I know here, there’s this really big spectrum where support happens. And it can be quite hard for someone to get their head around that it might not be counselling that they’re asking for.”

Melanie Calvesbert agrees. “People want to get back to normal - whatever normal is for them - and then there’s the trying to still walk home from the restaurant where they’re working until 11 o’clock at night, and then realising, ‘oh. I can’t do this’.”

ACC currently pays for counselling for the victims of sexual violence, after criticism of the way it handles sensitive claims. Last year, it was reported that the corporation was bracing for a significant increase in the number of sensitive claims in the next six years as the stigma around sexual violence is increasingly broken down in New Zealand.

But navigating that system can be difficult - just knowing where to go to ask for help can be hard. Eleanor Butterworth says Rape Crisis gets calls from people that have been ringing round trying to find where they can go to get help, and what the differences between agencies, counsellors, and psychotherapists are. “That’s quite a hard thing to be doing.”

Tso says some cases can be quite complex. “A degree of expertise, and considered assistance that provides value and doesn’t do harm ... that’s of real value.”

But the array of services can be quite confusing, he says.

“People want to get back to normal...and then there’s the trying to still walk home from the restaurant where they’re working until 11 o’clock at night, and then realising, ‘oh. I can’t do this.”

One of the “intangible” costs to a victim is time. “There is a cost to recovery, and to getting your life back on track. It may be about jobs, or having relationships and the cost involved in that, let alone a court hearing, and having to take time off that, and getting to court, and understanding the court process.”

Karen says she felt supported throughout Rewa’s trial, but not all his victims would say the same.

Calvesbert says while a number of organisations are struggling to support the victims of crime, there are pockets that have improved, and she points to the specialist victim advisors at the courts, saying the difference they have made is significant.

“Time has to be spent engaged in that justice process,” says Kevin Tso. “But also in actually regaining one’s own mana and self-confidence in the world and engaging with one’s own community. All those things are going to take time, and do have some sort of cost, no matter how you define that.”

And that recovery is different for every person, and not always a straight line. Two victims, of very similar crimes might have incredibly different needs.

For Karen, the worst thing is unexpected triggers. “His ugly mug pops up on TV all the time, because of the Teina Pora case. And I hate that. You’re on your iPad in the morning [reading the newspaper] and oh my God there he is. I still find that really distressing, after all this time.”

It’s not always immediately after the attacks that people need the most support, she says. “They need to be able to go back and get support whenever they need it.”

Butterworth says there are high correlations between childhood trauma and things like psychosis and homelessness. She points to some of Rape Crisis’ clients who are either homeless or have been, and who have been out of home since they were 13 or 14 because of abuse.

“Their whole lives have gone down a particular track and I really do believe for these people there’s a lot of unravelling that has to happen, but we have to get back to what made them leave home at some point.”

“We’ve worked with lots of people who have ended up really transient, because of trying to find a sense of safety.”

While most sexual assaults aren’t reported (the Ministry for Women estimates 9 per cent of incidents are reported to police), Tso believes more people are coming forward. “One would hope that’s going to be more and more the case. That’s an important means by which actually people can feel freedom to come forward without being stigmatised or having some judgement put on them.”

“There are the costs that are personal and are associated with something specific,” says Butterworth. “As members of society, we each have a cost put on us, and I look at some of the most maginalised people that we work with here, who left home at 13, have never had jobs, have convictions from trying to survive, or that sort of thing, and their value as members of society is going down.”

“What I mean by that, is what chance will people take on them to add value to their lives? Will someone ever give them that first job, rent them a home they choose, offer friendsip and make room in their community.”

“[Their] value as a human being, which has a cost-value in our society, is also dropping. And that’s pretty shit.”

If you’ve been the victim of a crime, help and resources are available.