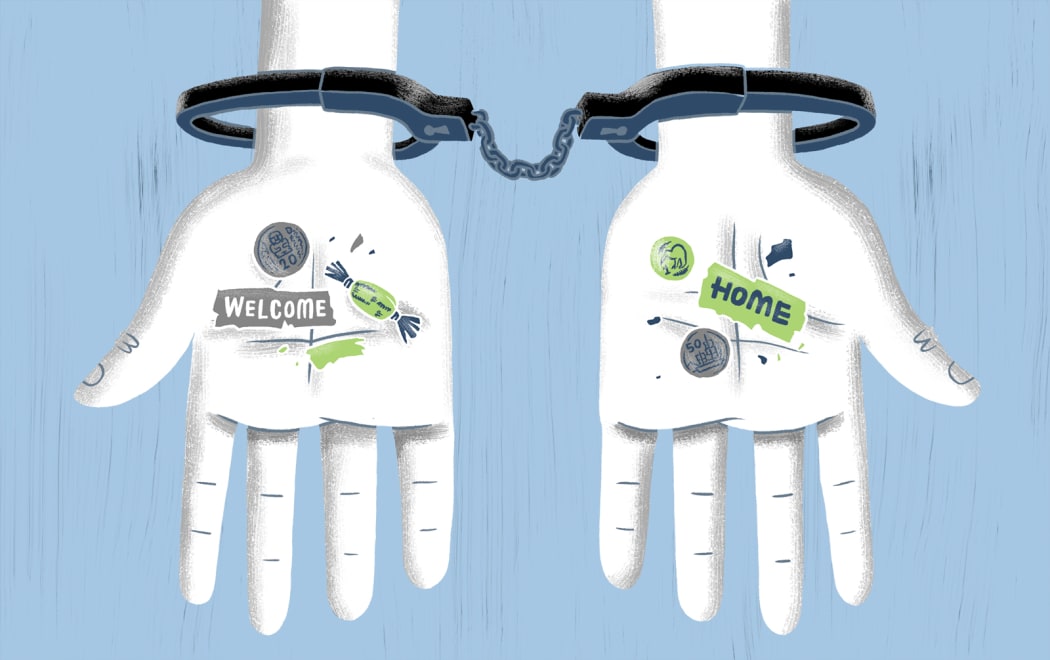

The government is fighting harder than ever to get back billions owed by former students overseas. While young Kiwis think the tactics are all wrong, they seem to be working.

Photo: Illustration: Toby Morris

After five years at university, Liam Gilbertson racked up a loan that he describes as a “pretty sum of 55k!” Clearing his debt with minimum payments would take more than 20 years.

With prospects like that, the idea of accumulating interest on top of an already mammoth amount could be anxiety-inducing. But for Liam, being stuck in New Zealand is worse. He left home earlier this year hoping to put his industrial design degree to good use in Europe.

“New Zealand is such a small country to try and financially barricade yourself in if you’re looking for more than it currently has to offer. I feel like I would suffocate if I stayed home until I had paid off my student loan.”

The average student loan is $20,371 and while the number of students borrowing money is decreasing, debt is soaring.

Student debt currently sits at about $15 billion - an amount which has grown from $7.5 billion in 2005. If student debt was to be divided evenly between every single person in New Zealand, each infant, child and adult would owe about $3200.

Since 2010, the National Government has put its foot down. It’s working harder than ever to get money back from borrowers living overseas - the people it sees as responsible for the ballooning debt - by making it easier to pay from abroad and shortening repayments holidays.

The government has also acted on its threat to arrest defaulters with two people detained at Auckland Airport earlier this year.

And, in a move likely to send shivers down the spines of some of the 650,000 Kiwis living in Australia, IRD is teaming up with the Australian Tax Office next month to get the contact details for New Zealanders who aren’t paying back their loans.

“I couldn’t think of a more fear-mongering way to scare people into repaying their loans or a quicker way to ensure that those with loans who leave the country will have second thoughts about coming back,” says Liam.

“The point of creating a nest egg is not to chase away the hen.”

Fear-mongering or not, the tactics seems to be working. So far, $311 million worth of additional repayments have been collected, including more than $100 million in the past 12 months.

According to Tertiary Education Minister Steven Joyce, the IRD is currently collecting $24 for every $1 invested in collection.

“We are confident we now have an effective programme that will lower the default rate of student borrowers living overseas over time and, most importantly, generate hundreds of millions in re-paid loans that we can invest in the next generation of students,” he says.

TOUGH TACTICS

Liam decided to leave home earlier this year and, after jostling around for a while, he settled in Rotterdam, Netherlands. While he managed to land a prestigious internship, he still has to work two extra jobs to stay afloat financially.

“Those internships are great but they make minimum wage look like luxury and they don’t always have a full contract at the end of them.”

He’s on a repayment holiday which means he still accumulates interest on his loan but can postpone making payments for the time being. That all comes to an end in March next year, meaning IRD will come calling.

“I don’t think I will have any choice but to come home or try working doing something other than what I’m really looking for,” he says.

Liam Gilbertson: "I feel like I would suffocate if I stayed home until I had paid off my student loan" Photo: Supplied

Repayment holidays were cut from three years to just 6 months in 2012 - a move that NZUSA president Linsey Higgins says was “cold”.

“Three years was a great length of time to support that and the majority of graduates returned in that time. Six months, in contrast, is barely time to see anything or work overseas gaining new skills.”

“We don’t want to see a system where people declare bankruptcy to leave their student debt behind, but that is what the current environment is breeding,” says Higgins.

The loan balances of people who are declared bankrupt are completely written off. Since 2012, there have been 1651 cases of bankruptcy leading to $30 million of wiped debt.

Joyce says tougher measures were inevitable because people are simply not paying back their debt.

While the 110,000 overseas borrowers only represent 15 percent of everyone with a student loan, they make up 70 percent of all borrowers with overdue payments.

“Previous governments made no pro-active attempt to collect student loan repayments from those living overseas, putting the task in the ‘too hard’ basket,” says Joyce.

The government has began arresting people with overdue payments at the border as they try to enter or leave New Zealand. It’s a drastic move which Joyce insists is a “last resort”.

The first ever arrest over student loan repayments was made in January when Cook Islands maths teacher Ngatokotoru Puna was handcuffed at Auckland Airport for failing to repay more his student loan which had spiralled from $40,000 to $130,000 while he’d been overseas.

Higgins says arresting people is the last thing that will encourage anymore to come home. “We know that fear is a poor motivator when it comes to any situation and using it in this instance is breeding hostility and resentment.”

Photo: Illustration: Toby Morris

Puna’s arrest, in particular, showed a complete failure on the part of the government, she says.

“[He] was from a dependent nation of New Zealand and should not have had interest added to his loan in the first place. It’s the failure of IRD to support those who are in dependent nations with student loans to make repayments.”

A second arrest took place in June when a woman was arrested at Auckland Airport as she tried to board a flight to Australia. She appeared in the Manukau District Court the next day.

Currently, around 20 people are being actively monitored by IRD for possible arrest when they return to New Zealand. But the tactic isn’t likely to stop New Zealanders leaving the country.

The Financial Education and Research Centre, who are following 300 young people in a longitudinal study, found 44 percent were considering moving abroad for better money within the next two years.

According to data from Statistics New Zealand, there are still thousands of young New Zealanders heading to Australia after their studies.

FALSE ADVERTISING

For Lucy von Sturmer, staying in New Zealand wasn’t a viable option.

The 28-year-old left shortly after graduating with a post-graduate degree. She’d been working a minimum wage job which showed little prospects of turning into something more.

“My family were so proud I was at university, and I felt this great sense of direction and success in my undergrad years. Once I graduated however, nobody had any advice on what kind of career direction I could take - or what kind of job I was qualified to perform.”

By the time she finished her honours in New Media, her loan clocked in at about $40,000. Her debt weighed heavily on my shoulders but with few opportunities for work in her field, she packed up and left.

“I felt like I had no other option...and I had little faith I'd be able to pay it back anyway. Staying to avoid interest never occurred to me.”

Lucy moved to Europe where she worked odd jobs, before landing a dream position in the Netherlands. She says it was the best decision she made.

She’s since travelled to Nairobi, Johannesburg, San Francisco and Indonesia in her role reporting on the events and achievements of the organisations she worked for.

Lucy von Sturmer: “I remember feeling like University was scam; how could they ‘market’ our future to us?" Photo: Supplied

While she’s glad she went to university, Lucy isn't convinced it’s the best option for young New Zealanders, despite what they say.

“I remember feeling like university was scam; how could they ‘market’ our future to us? How could they sell us this idea that we'd have a promised future by entering university? All I remember was classes of 100+ students, little contact with tutors and lecturers, and exams in which waffling answers, and regurgitating a few key ideas presented in class, let you pass.”

“C's do get degrees. But what do degrees get you? The degree alone would never had got me to where I am.”

Lucy has not only managed to get her loan down to $15k, she’s also bought a house - something she knows she could never have done in New Zealand where Auckland’s average house prices have just hit $1 million.

GONE FOR GOOD?

Ashley* isn’t sure she’ll ever come back to New Zealand.

She graduated with a Law and psychology degree in 2013 and built up a $53,000 loan but isn’t currently earning any income since she’s volunteering fulltime.

Ashley left for the Middle East in 2014 but her application for an interest free loan was rejected because, according to IRD, her volunteer work was not on the OECD list of countries receiving development assistance.

“While I don’t think that every person volunteering abroad should automatically be exempt from interest-free loans, it seems the policy is being applied very rigidly with little consideration given to the actual organisation one is volunteering for,” she says.

Photo: Illustration: Toby Morris

She makes the minimum repayment obligations of about $4,000 each year with help from her family. The payments are just enough to pay off the incurring interest.

“I decided to study, but I had no choice to take out a loan. I chose to come volunteer abroad for a greater cause than myself, and unfortunately the interest I am paying on my loan is additional sacrifice I have had to accept in this process.”

Steven Joyce says New Zealand has one of the most generous student support systems in the world with a government that spends 48 percent of the budget for tertiary education on financial aid to students, while the OECD average is 22 percent.

“We do not want to stop graduates going overseas...However, we want to make sure borrowers understand that when they choose to take a student loan they have a responsibility to repay, whether they are in New Zealand or overses.”