Staying connected.

The concrete environment of the city been sculpting Māori identity since the urban drift began early last century. Back in 1936, 83 percent of Māori lived in rural communities, but 50 years later that statistic had flipped - 83 percent were living in cities.

And that drift is still happening today.

We spoke to nine young Māori who left homes where tikanga was part of everyday life and moved to Wellington. They share how they hold on to their māoritanga.

WHETU MACKIE

Photo: Chev Hassett

Hey bro, tell me about yourself and where are you from?

Kia ora my name is Whetu and I’m from Te Arawa originally but born and raised in Hamilton, but my dad is from Te Arawa and my mum is from Ngāti Porou and Te Atiawa.

You’ve moved to Wellington now. How does that feel?

I found it hard after the first three months just because I had cultural withdraw. I came from Hamilton where te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and Māori practices are real dominant and it’s just a normal lifestyle. Day-to-day basis everything was done from a Māori structure or base.

Moving here I found it hard after that, not to lose my connection with being Māori. That’s because I could feel my language fading away from me real quick.

How do you keep connected to your māoritanga?

Just listening to songs, doing assignments in Māori, speaking to myself in Māori and what helps is listening to Māori oratory and picking out new words to learn.

Last thing, what is being Māori today for you?

Being Māori today, I don’t think it is as hard as it used to be because there is a lot of information out there. I think the motivation to be Māori and acknowledging yourself as being Māori is where most people are failing. Not willing to give it an effort because it’s a thing that isn’t being taught outside of Māori communities and it isn’t as encouraged in mainstream institutes.

Also, there aren’t enough people today teaching sacred teachings specific to your iwi. I don’t see Māori, I more see iwi, as we are individual in ourselves. But we’ve been titled by the other, under an umbrella, as one.

TE WAINUIĀRUA POA

Photo: Chev Hassett

Hey Te Wainuiārua, can you introduce yourself?

Kia ora, ko Te Wainuiārua Poa ahau. He uri tēnei nō te awa o Whanganui nō Ngāti Maniapoto hoki. I tipu ake au i a Whanganui, kei reira e noho ana ōku pou hei kawe ngā whakaruruhau o tōku whānau, arā ko ōku mātua me ōku tupuna.

You have been living in the city for a while now, talk to me about that?

Definitely a culture shock, I knew it was going to be like that because my sister moved down here before me. The one thing I had to get used to is that Māori do not dominate down here, we are a minority and I had to get used to not seeing my coloured face around as much as I was used to.

Moving away from family was hard and I cried the first day. I think it is hard for Māori who come here because Māori value family so much and they are the core of our life. You come here to better yourself but now you must motivate yourself on your own when you’re used to a community that backs you.

For you, what is it to be Māori?

People say being Māori is a feeling, but I don’t think it’s just how you feel being Maori. It’s whakapapa. You can translate that word and it can mean the placing of layers which is what we are as Māori, we are the placement of our tupuna’s layers. Not only do you connect to your Māori mother or Māori father but you connect to a long line of Māori. You’re a living legacy of your tupuna.

I think being Māori is whakapapa, it is a birthright. You were Māori before you were in your mother’s womb, before you breathed tihei mauri ora!

Anything else?

People need to know and not only know but understand and accept that Māori are not who they used to be. Māori don’t look like they looked compared to the old days. People need to accept that Māori are more diverse now and they need to appreciate that. Not only in looks but in their interests. Contemporary Māori are leading the pathway to diversity.

AHLIA-MEI TAALA AND MING RANGINUI

Photo: Chev Hassett

Tell me about yourself Mei, and where you whakapapa to.

My names Mei and I’m from Atihaunui-a-Paparangi, in Whanganui. I never grew up in Whanganui and I have felt a bit disconnected but I’ve always had this connection to the awa.

Being from the river, how do you feel about it now with everything going on?

With the Whanganui river becoming like a legal person now, I think one of the MPs were criticising it because they could not understand personifying something that’s not a person.

It is sad that it is polluted there now and I do miss it when I leave.

Now that you've come down here how are you finding it?

I moved here last year and I was really shocked how white it was. My high school was diverse and I was in the Māori unit and coming here I was so shocked hearing what people would say.

So tell me about yourself too, Ming.

Kia ora, I’m Tibet but I didn’t have a name for a week when I was born and so my mum called me Ming but my dad named me Tibet because he wanted me to have the qualities of a Tibetan monk. I’m from Atihaunui-a-Paparangi and when I am up the river I feel like I belong there and it's home.

How do you feel about your river now after what has gone on because I know it is special to your iwi?

It is really special. It should have been like this forever and reading the comments that were on Facebook there are so many ignorant people, it makes me upset.

What is it like being an urban Māori?

The primary schools I went to were predominantly white and I could count the number of Māori on my hand. You could tell how you were different and you tried to fit in with them. And you’d try distance yourself from your culture.

Then going to high school there were more Māori and then I did not feel Māori enough, like where am I?

What do you think makes you Māori?

I think you’re either Māori or you’re not. You can’t just be like you’re a little bit, you’re just Māori.

KAHU KUTIA-BALDWIN

Photo: Chev Hassett

Tēna koe, can you introduce yourself for everyone?

Kia ora, so I’m Kahu Kutia-Baldwin. Baldwin is the name I get from my mum, so that’s my Pākehā whānau and they’ve been based in Pūtāruru, in Waikato. Kutia is the name I get from my father, on my taha Māori, Ngāi Tūhoe, but the name originally comes from Ngāti Porou.

What’s it like being from Tūhoe?

Being Tūhoe, obviously, we call ourselves Ngā Tamariki o te Kohu - Children of the Mist. Mist is a huge and special part of it and Papatūānuku plays a big part as well.

For me at least, a lot of being Tūhoe is where I come from. I grew up at the northern entrance of Te Urewera, where you go up into the hills and the road becomes dirt and gravel. I lived up there for 15 years or something, and Tūhoe for me is that land.

The land itself, I think, is so closed up and Te Urewera is essentially like a fortress, which is how I think we’re so lucky to have a lot of our cultural practices stay the same. I think there’s a lot of history of activism in Tūhoe, which I’m really proud of.

How do you feel living in the city and are you enjoying it?

I do like it down here, but it’s different. It’s very different from Whakatāne and from Waimana, a lot bigger, a lot more people. It’s obviously a bit harder to get out to quiet places that are like home.

But I think it’s interesting being here because it’s such a different place from home and I learned something about myself and how people perceive me. At home most people are Māori and here it is suddenly a thing.

I think it is cool when you find other Māori here because there is a sense of whanaungatanga and there is a lot of contemporary Māori stuff coming out and it is cool to be a part of it.

Last thing how do you keep up with your māoritanga?

Just for myself, the most important thing is to connect and to be connected to the whenua. Down here, that means going for a walk in the ngahere, climbing one of Wellington’s maunga, or going for a swim.

My wairua is unbalanced if I’m not doing that. I’m also trying to find connections with other people and collaborating with other Māori who I’ve met in the city.

EMIKO SHEEHAN

Photo: Chev Hassett

Kia ora, can you introduce yourself my friend?

My name is Emiko, I am from Ngati Maniapoto and grew up in Hamilton, my hapu is from Te Kuiti and that is where my marae is. At my marae it is all rolling hills and farmland, you cannot see any township from the marae and it's cold!

Why did you choose to move to Wellington?

I have always liked Wellington and I wanted to move into a big city. Before coming to Wellington I lived in Japan and before Japan I was living in Hamilton my whole life and I just wanted to get out because it was a boring city.

Since living in Wellington I have started to miss it [Hamilton] and since studying here I am more interested in learning my whakapapa and te reo.

Being in the city do you find it hard to keep your māoritanga?

Yeah, I can easily go out in Wellington and not interact with that part of me. It is like every time I do want to bring it up or something happens it is an effort to do it, I'm also quite conscious of it now because of studying. I'm more aware of social structures in New Zealand and I am more aware of my māoritanga and I’m not being ashamed or ignoring it.

What do you do or have that help keeps your māoritanga?

I try to speak Māori words where I can and do a lot of readings by Māori people. I have started to go to [te reo] lessons. I also have my ta moko and I have taonga at home, a wakahuia my dad made for my 21st and my mum is a great weaver and she made me a kete.

Wow, now just before we end this can you talk a bit about your ta moko?

I got it when I was 18, so five years now. It means a bunch of different things and because it is under my arm and it's close to my body I see it as very precious. it was a gift to me from my dad and I feel like I need to treasure it. It also reminds me that if I don't speak the reo or sing a lot of waiata I am still Māori. So it is just a reminder to feel strong to myself.

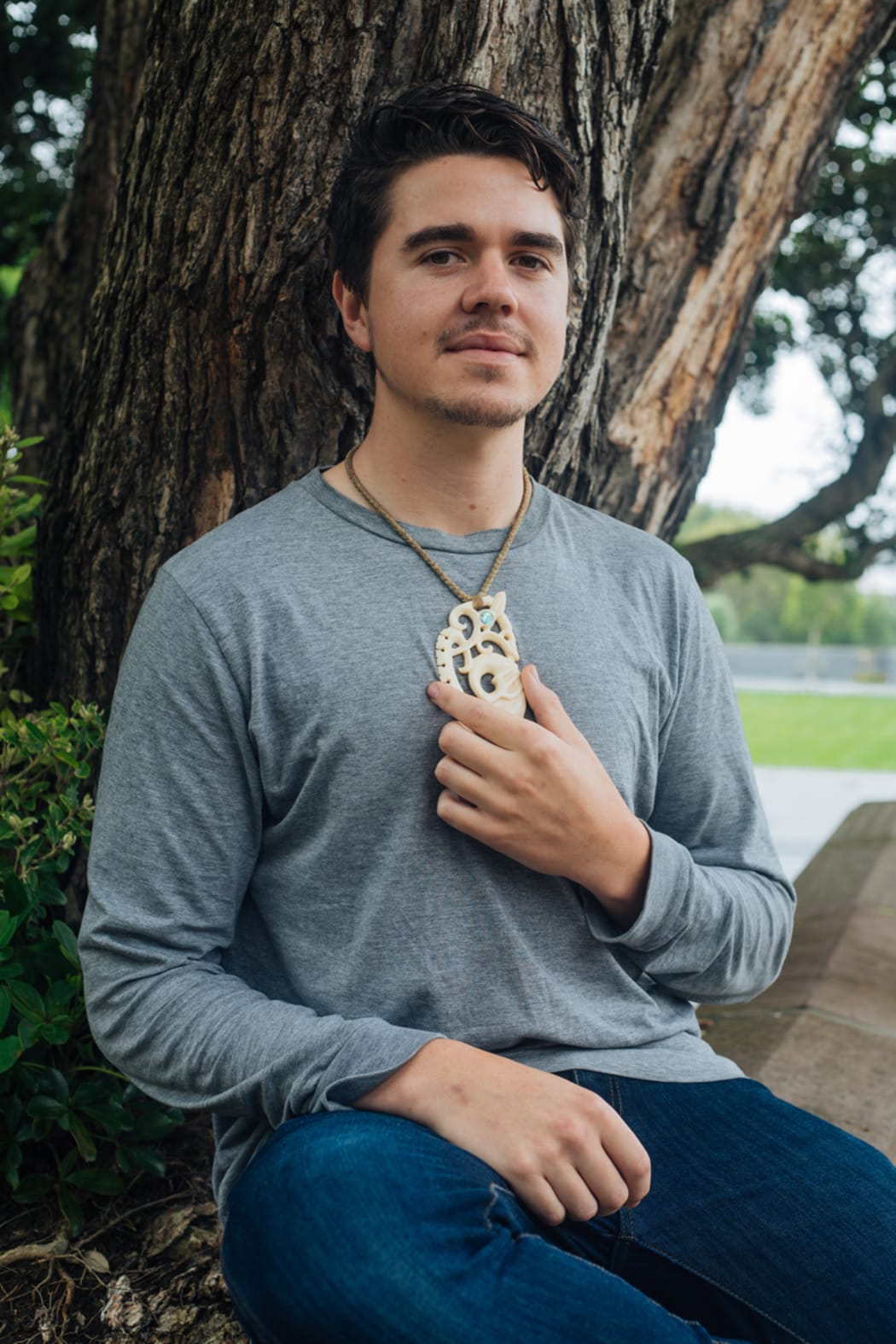

CLINTON JUSTIN BLACKLEY

Photo: Chev Hassett

Kia ora bro, tell me about yourself?

I grew up in Palmerston North and lived there my entire life and did not leave there until moving to Wellington.

Mean. Are your iwi from Palmy?

Nah, actually they're from Wellington - Te Atiawa, Ngāti Raukawa and Ngati Toa. So actually, my iwi are from down here and Waikanae, my marae is Whakarongotai. I haven’t been there in a while either. It's good to go past there on the way back home.

Can you tell me something interesting about your iwi?

Yeah, our great, great, great grandfather was a politician and was the chief of our iwi. His name Wiremu Te Kakakura Parata.

He was in a famous law case and a lot of students study this. He gave some land to the government to create a church and they did not use it for that and they just took it off him. He became a politician to stop that and he took it to court and he used the Treaty of Waitanga to say you cannot do this to us.

The judge said that the treaty was not a legal document and from this event sparked a lot of those conversations around the treaty.

Do you think it has changed you moving to the city?

Yeah, I’ve been able to reconnect to my iwi and hapu. Also, being a part of Kokiri (Māori Association) has really helped, I feel like it is making me a better designer, giving me more of an advantage and more of a better person I guess.

How do you feel being Māori?

It’s exciting and it is a bit daunting. I didn’t identify myself really until coming to university. When I came to university I started to show it a bit more and I guess people started to see that. When they look at this [taonga] it such a presence to look at and it is amazing to see, people started to ask about what it means.

I feel like [māoritanga] is starting to come forward and I did not realise it was progressing until I looked back at it.

Yeah, your taonga is amazing. Can you tell me what it represents?

It is a manaia (guardian) and It kind of revolves my family and when went through some hard times. Mum pushed through hard yards to get us here and I know she’s happy to see us at university. So yeah, it incorporates my family and reminds me that they’re behind me. I know it is going to be a part of me know.

TE HANA TAILA GOODYER

Photo: Chev Hassett

Ko Ngati Raukawa-ki-te-Tonga te iwi. Ko Waoku te puna, te rohe, te tūrangawaewae. Ko Te Hana Taila Goodyer tōku ingoa.

A little bit about myself, I am a 22-year-old graphic designer living in Wellington. I guess I am into my fitness with muay thai, but for me visual creativity is my number one. It ties into everything I’ve done since a young age.

How was it for you growing up?

I grew up on a family farm, and for the most part I resented it. Seeing what other kids had and their freedom living in town I was (at the time) jealous and ignorant. I went by my middle name because that’s what my parents enrolled me in school as, so looking back it wasn't until I had a Māori primary school teacher who began calling me by my first name, a Māori name, that I realised there was something more to myself.

Acknowledging to be Māori made me feel included in a shared identity, that felt right, that’s what I remember feeling at that time - pride.

Now after that did you experience a change when moving into the city?

I have always wanted to move to the city because I did not have a lot of independence growing up. This was like breaking free and doing my thing, being independent and stand on my own two feet.

Last thing, what is it like being here in the city?

Well recently going from varsity “the student life” to a tedious full-time work schedule really sucked at first. But I constantly have to remind myself I should be grateful that I have a job in my studied profession.

Also, I‘ve found that now I go by my first name it gives me a point of difference – Not a designer who happens to be Māori, but a Māori designer.

Although there are times where I have felt that I have filled the void of being the “token” or where my cultural identity has been backhandedly dismissed. I understand there’s not an easy solution, but learning to navigate these urban spaces of predominately pākehā with diligence and dignity in who I am, is the work that I have cut out for me.

JACOB MCGREGOR

Photo: Chev Hassett

Hey, tell me about yourself?

Kia ora my name is Jacob McGregor and I’m Ngāti Raukawa ki te tonga, Ngā Rauru, Te Whanau-a-Apanui and I grew up in Whanganui.

Awesome. So, you’re from Whanganui. What is it like growing up there?

It was real cool, I loved growing up on the river and it is very different to Wellington.

Whanganui is quite rural, it’s very conservative but I loved growing up there because it was very quiet and peaceful. It was also close to dad’s and mum’s family so I could always connect to my roots. Ngā Raura is basically Whanganui, but just on half of it in the north.

After growing up in a place like that, how did you find Wellington?

It was really different and just so many people. Very fast paced in comparison to Whanganui, very liberal and open, also it is very carefree here. People are carefree back home but it is just a different type of carefree.

There is a certain stereotype or status people follow (in Whanganui) and so moving down here was cool, but there is less brown people and more snobby people too. The lack of Māori down here was noticeable too.

Not seeing any brown faces in the city how did that make you feel?

I felt like I stood out a bit even though I don’t, because it’s Wellington. I just did not feel homely. It was a bit hard at first not having this immediate connection and even when I came to university the Māori here were awesome but they came from different backgrounds from what I was used to, when I was used to Māori from the Whanganui to Taranaki region.

Last thing, since you’ve been living here how do you personally keep connected to your māoritanga?

The marae is the main thing which keeps me connected, so the marae is just an awesome place to come. It has all these beautiful carvings and pou that are representatives of each iwi in New Zealand and it keeps us all connected.

As well as just being able to continue learning my reo and performing kapa haka, also serving and being amongst all the Māori initiatives where the marae is the centre for that. If I did not have this marae I would be quite estranged and separate from my māoritanga down here in Wellington.