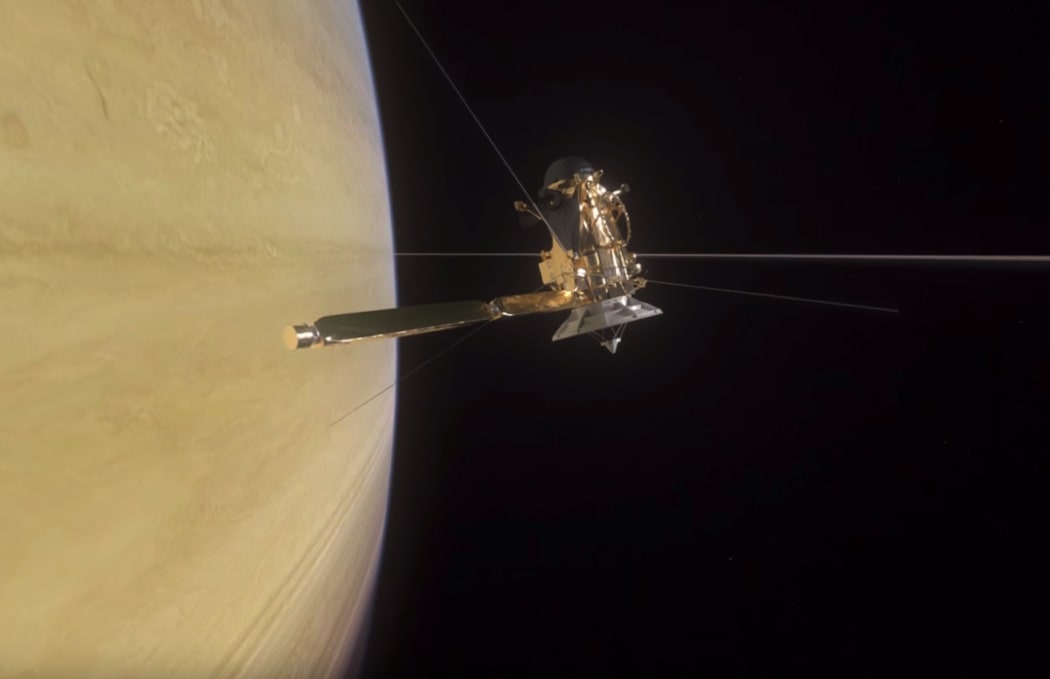

The Cassini spacecraft is making its final plunge into Saturn, taking its last pictures of the planet, its rings and its moons.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has entered the final chapter of its mission. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Engineers now have a precise expectation of when they will lose contact with the Cassini probe.

The spacecraft is being ditched in the atmosphere of Saturn on Friday, bringing to an end 13 years of discovery at the ringed planet.

The team hopes to receive a signal for as long as possible while the satellite plummets into the giant world.

But the radio will likely go dead at about 6 seconds after 4.55am local time at mission control in California, which is the time that antennas on Earth lose contact.

Because of the finite speed of light and the 1.4 billion km distance to Saturn, the event in space will actually have occurred 83 minutes earlier.

"The spacecraft's final signal will be like an echo. It will radiate across the Solar System for nearly an hour and a half after Cassini itself has gone," said Nasa project manager Earl Maize.

"Even though we'll know that, at Saturn, Cassini has already met its fate, its mission isn't truly over for us on Earth as long as we're still receiving its signal."

A giant dish in Canberra, Australia, will be in prime position to track the probe. Others across the globe will be working in support.

Cassini is in the process of taking its final pictures of the Saturnian system.

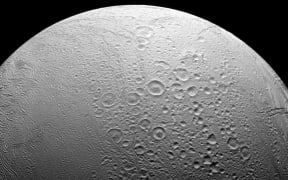

These will include views of the moons Enceladus and Titan, which harbour huge volumes of liquid water beneath their icy surfaces and where scientists believe simple lifeforms might be able to eke out an existence.

"And then… we're going to look on the dark side of Saturn at that point where Cassini will be plunging into the atmosphere, looking in the near-infrared and the ultraviolet, trying to get some pictures of Cassini's final home inside the planet Saturn itself," explained Nasa project scientist Linda Spilker.

All pictures must be downlinked and the cameras switched off before the death plunge can begin.

The data rates flowing back from Saturn will not support imaging on the way down. Instead, Cassini will be configured to run only those instruments that can sense the planet's near-space environment, such as its magnetic field, or that can sample the chemical composition of its gases.

Hunter Waite leads the probe's Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS).

"We'll be able to look at some important constituents that we know are there because we've been measuring them, but we'll get a better idea, for example, of the hydrogen to helium ratio, and that's important in terms of understanding the formation and evolution of Saturn," he said.

In the final three hours or so before impact on Friday all data acquired by the spacecraft will be relayed straight to Earth, bypassing the onboard solid state memory.

The end when it comes is going to be a bittersweet moment. The probe has dazzled all those who have followed its progress, including Jim Green, the head of planetary science at Nasa.

He said Cassini had re-written the textbooks on where one might try to find life beyond Earth.

"No-one ever thought that we could go to the outer part of the Solar System," he told BBC News. "That's where water, because the Sun hardly shines there, should be frozen solid - and you have to have liquid water to be able to have life.

"And now we're finding whole moons with oceans of liquid water that have been that way for 4.5 billion years. That blew our minds."

Looking to the future, many of Cassini's scientists are eager to return with new, more capable spacecraft.

Mission proposals have been submitted to Nasa that include instrumented boats that could float on Titan's seas, and life-detection probes that could be flown through the jets of water that spout from the southern polar region of Enceladus.

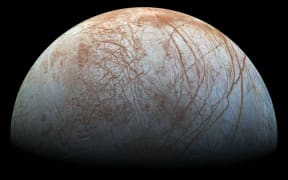

In the near term, though, many of the same researchers will be working on America's Clipper mission to Europa, a moon of Jupiter that in many ways is just a big version of Enceladus. And in tandem, European Cassini scientists will be targeting Ganymede, another jovian moon that is bigger even than Titan and which is suspected also of hiding a huge ocean of liquid water under its icy shell.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a joint endeavour of Nasa, and the European and Italian space agencies.

- BBC