The American-led Cassini space mission to Saturn has just come to a spectacular end.

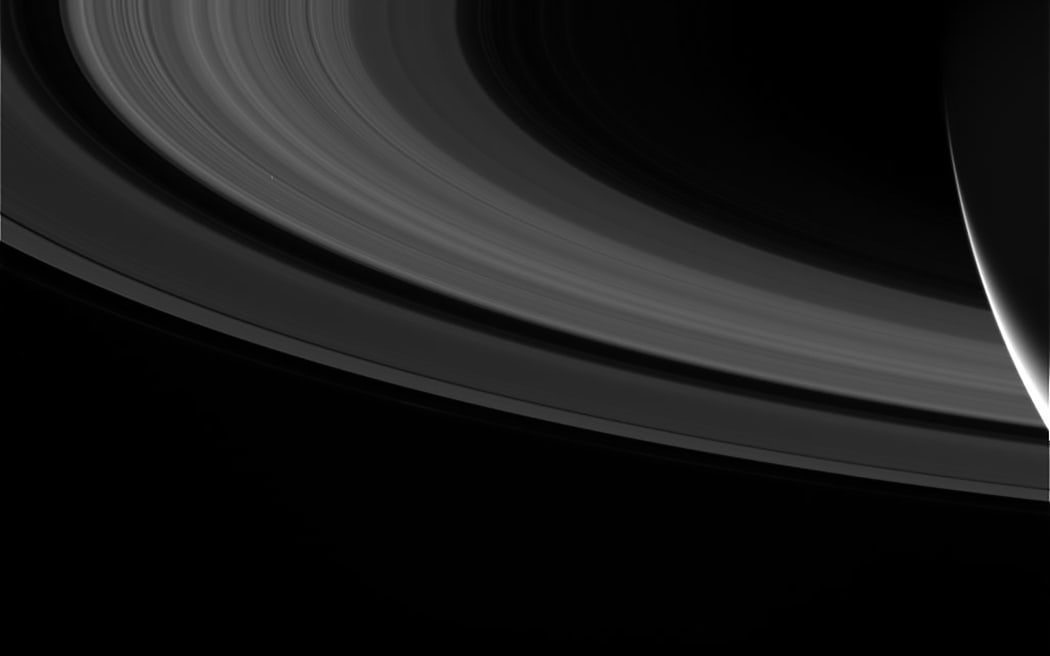

This image of Saturn's rings was taken by Cassini in its last days of operation Photo: AFP PHOTO / NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute

Controllers had commanded the probe to destroy itself by plunging into the planet's atmosphere.

It survived for just over a minute before being broken apart.

Cassini had run out of fuel and Nasa had determined that the probe should not be allowed simply to wander uncontrolled among Saturn and its moons.

The loss of signal from the spacecraft occurred close to the prediction. At mission control, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, the drop-off was timed at 4.55am local time.

NASA's Earl Maize addressed fellow controllers: "Congratulations to you all. This has been an incredible mission, an incredible spacecraft and you're all an incredible team. I'm going to call this end of mission. Project manager off the net."

The statement brought restrained applause and some comforting embraces.

JPL staff react as the probe loses signal for the last time Photo: AFP

The loss of signal indicated that the probe was tumbling wildly in the planet's gases. It could have survived the violence for no more than about 45 seconds before being torn to pieces.

Incineration in the heat and pressure of the plunge was inevitable - but Cassini still managed to despatch home some novel data on the chemical composition of Saturn's atmosphere, ending one of the most successful space missions in history.

In its thirteen years at Saturn, Cassini has transformed our understanding of the sixth planet from the Sun.

It has watched monster storms encircle the globe; it witnessed the delicate interplay of ice particles move through the planet's complex ring system; and it revealed extraordinary new insights on the potential habitability of Saturn's moons.

Titan and Enceladus were the standout investigations.

The former is a bizarre place where liquid methane rains from an orange sky and runs into huge lakes. Cassini put a small European robot called Huygens on Titan's surface in 2005. It returned a remarkable image of pebbles that had been smoothed and rounded by the action of that flowing methane.

Cassini also spied what are presumed to be volcanoes that spew an icy slush and vast dunes made from a plastic-like sand.

On Enceladus, the observations were no less stunning.

This moon was seen to spurt water vapour into space from cracks at its south pole. The water came from an ocean held beneath the icy shell of Enceladus.

When Cassini flew through the water plumes, it showed that conditions in the sub-surface ocean were very probably suitable for life.

Today, scientists are already talking about how they can go back with another, more capable probe to investigate this idea further.

A great many of those researchers have been gathered this week at the nearby campus of the California Institute of Technology. They watched a feed from the control room at JPL on giant screens.

Jonathan Lunine, from Cornell University at Ithaca, New York, spoke for many when he said: "I feel sad but I've felt sad the whole week; we knew this was going happen. And Cassini performed exactly as she was supposed to and I bet there is some terrific data on the ground now about Saturn's atmosphere."

Nasa Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker said: "When I look back on the Cassini mission I see a mission that was running a 13-year marathon of scientific discovery. And this last orbit was just the last lap. And so we stood in celebration of successfully completing the race. And I know I stood there with a mixture of tears and applause."

Although the probe has gone its science lives on. It has acquired a huge amount of data that will keep researchers busy for decades to come. A lot of it has barely even been assessed.

"Linda Spliker and I were joking earlier that those last few seconds of the Cassini mission - our first 'taste' of the atmosphere of Saturn - might be a number of PhD theses for students to come," JPL director Michael Watkins said. "So, even in those last few seconds, it will continue its re-writing of the textbooks."

-BBC